Table of Contents

Introduction

In the vast timeline of ancient Indian history, some dynasties shine brightly due to their grand empires and monumental achievements, while others, though less glorified, played crucial transitional roles that shaped the subcontinent’s political and cultural landscape. One such overlooked yet historically significant lineage is the Kanva Dynasty.

The Kanva Dynasty, which ruled from approximately 75 BCE to 30 BCE, succeeded the Shunga Empire in the region of Magadha, marking a pivotal phase between the end of Mauryan-influenced governance and the rise of regional powers like the Satavahanas. Founded by Vasudeva Kanva, a Brahmin minister who overthrew the last Shunga ruler, this dynasty may not have enjoyed prolonged rule or vast territorial conquests, but its impact on maintaining socio-religious continuity and ensuring administrative stability during a fragmented era cannot be underestimated.

Despite its relatively short duration and the scarcity of extensive historical records, the Kanva period serves as a critical bridge in Indian history, offering insights into the political flux that characterized the post-Mauryan era. At a time when India was transitioning from large centralized empires to smaller, regional kingdoms, the Kanvas preserved the Brahmanical traditions and political mechanisms that had been dominant since the time of the Mauryas. Their reign represents not just a change in leadership but a symbol of the enduring influence of Brahmanical authority and its intertwining with royal power.

Studying the Kanva Dynasty allows historians and enthusiasts alike to better understand the evolving nature of power, patronage, and politics in ancient India, especially in the Gangetic heartland. It sheds light on how dynastic transitions occurred—not always through wars or invasions, but sometimes through internal palace intrigues and ministerial takeovers, revealing the complex texture of Indian polity.

In essence, the Kanva Dynasty may not dominate history textbooks, but it occupies a vital position in the chain of India’s ancient dynastic succession, standing as a testament to an era of quiet but meaningful political transformation.

Historical Background

The Kanva Dynasty did not emerge in a vacuum—it rose from the dying embers of another powerful lineage: the Shunga Dynasty, which itself had succeeded the mighty Mauryan Empire. To fully appreciate the origins of the Kanvas, it is essential to understand the political turbulence and court dynamics that marked the final days of Shunga rule.

The End of the Shunga Dynasty

The Shunga Dynasty, founded by Pushyamitra Shunga around 185 BCE after assassinating the last Mauryan emperor, had managed to hold power for nearly a century. Although initially militarily robust and culturally influential, especially in promoting Brahmanism, the later Shunga rulers were considerably weaker. The dynasty was on the verge of disintegrating by the time Devabhuti, the final emperor, took the throne.

Devabhuti is often described in historical and Puranic sources as an indulgent and ineffective ruler, more absorbed in personal pleasures than governance. His court, riddled with intrigues and corruption, became vulnerable to internal usurpation. With royal authority deteriorating within the Shunga dynasty, Vasudeva Kanva—a high-ranking Brahmin adviser—began consolidating influence behind the scenes.

The Rise of Vasudeva Kanva – From Minister to Monarch

Vasudeva Kanva was no ordinary courtier. As a Brahmana and a trusted minister, he held both political clout and religious legitimacy—an important combination in an age where royalty and religious authority were deeply entwined. Puranic sources suggest that Vasudeva, disgusted by Devabhuti’s moral and administrative decline, orchestrated a palace conspiracy that led to the king’s assassination around 75 BCE.

However, Vasudeva’s coup was not merely an act of ambition. It was also seen as a restoration of dharma—a move to preserve righteous governance and uphold Brahmanical values at a time when they were believed to be endangered by the corrupt Shunga court. This ideological backing, combined with his strategic placement within the royal inner circle, helped Vasudeva Kanva legitimize his ascendancy to the throne.

The Founding of the Kanva Dynasty (c. 75 BCE)

With the fall of Devabhuti, Vasudeva established what would come to be known as the Kanva Dynasty, named after his lineage or gotra. The transition marked not just a dynastic change, but a shift in the structure of political legitimacy in ancient India. While the Mauryans and early Shungas had relied on military prowess and expansionist strategies, the Kanvas rose to power by leveraging religious authority and bureaucratic influence.

Though their territory was largely limited to Magadha and surrounding regions, the Kanvas managed to maintain a level of political continuity, preserving many of the administrative structures of their predecessors. The Kanva rulers, being Brahmins themselves, were strong patrons of Vedic rituals and orthodox Brahmanism, contributing to the continuation of Brahmanical traditions in the post-Mauryan period.

The ascent of Vasudeva Kanva marks a singular period in Indian history—a rare instance in which a Brahmin, not a Kshatriya, founded a reigning dynasty, upending conventional wisdom regarding varna-based governance. This also reflects the complex social dynamics of the time, where religious legitimacy could rival or even surpass military strength as a means of seizing power.

The establishment of the Kanva Dynasty marks a critical moment of transition in ancient India. It symbolizes the decline of Mauryan imperial legacy, the politicization of religious authority, and the restructuring of power around elite Brahmanical influence. Despite its relatively short reign, the dynasty’s origin story provides vital insight into the evolving nature of statecraft, legitimacy, and leadership during a formative era in Indian civilization.

Political History and Rulers of the Kanva Dynasty

The political narrative of the Kanva Dynasty is relatively brief but crucial to understanding the waning years of ancient India’s imperial period. Despite lasting only around 45 years (c. 75 BCE – 30 BCE), the Kanvas represent a significant transitional phase in Indian polity—one where religious elites assumed kingship, and dynastic legitimacy was forged not through conquest, but through internal court dynamics and Brahmanical endorsement.

Vasudeva Kanva – The Founder of the Dynasty

Role as a Minister in the Shunga Court

Before ascending the throne, Vasudeva Kanva served as a high-ranking Brahmin minister under the Shunga king Devabhuti, the last ruler of that dynasty. As a key figure within the Shunga administration, Vasudeva held considerable power and influence, operating from within the court’s inner sanctum. His background as a Brahmana also lent him religious legitimacy in a period where Brahmanical orthodoxy was resurging after the Mauryan emphasis on Buddhism.

His role as minister placed him at the intersection of governance and spiritual authority—a combination that would later form the ideological basis for his assumption of the throne. This position enabled him to observe and manipulate palace politics and eventually turn them in his favor.

Overthrow of Devabhuti

According to the Puranas, it was around 75 BCE that Vasudeva Kanva orchestrated the assassination of Devabhuti, the last Shunga ruler, effectively bringing the Shunga dynasty to a close. The act was framed not merely as a power grab, but as a necessary correction of adharmic rule, as Devabhuti was portrayed as a weak, decadent ruler more interested in courtly indulgence than state affairs. Some sources suggest that Vasudeva’s daughter or a court courtesan may have played a role in the plot, reflecting the covert and strategic nature of the transition.

Vasudeva’s seizure of power highlights a significant shift in the nature of dynastic succession—from hereditary right and military conquest to bureaucratic usurpation backed by religious ideology.

Consolidation of Power

After seizing the throne, Vasudeva worked swiftly to legitimize his rule, establishing the Kanva Dynasty, likely named after his gotra (clan). Though a Brahmin, his leadership was accepted due to the sanctity associated with the varna, and because his rule was seen as a moral correction of Devabhuti’s failed kingship.

While no extensive records of military campaigns exist, the Kanvas appear to have retained Magadha and surrounding territories. The dynasty focused more on internal consolidation, governance, and maintaining Brahmanical orthodoxy than on imperial expansion. Temples and religious institutions were likely supported, ensuring the dynasty’s alignment with the rising tide of Vedic revivalism.

Successors of Vasudeva Kanva

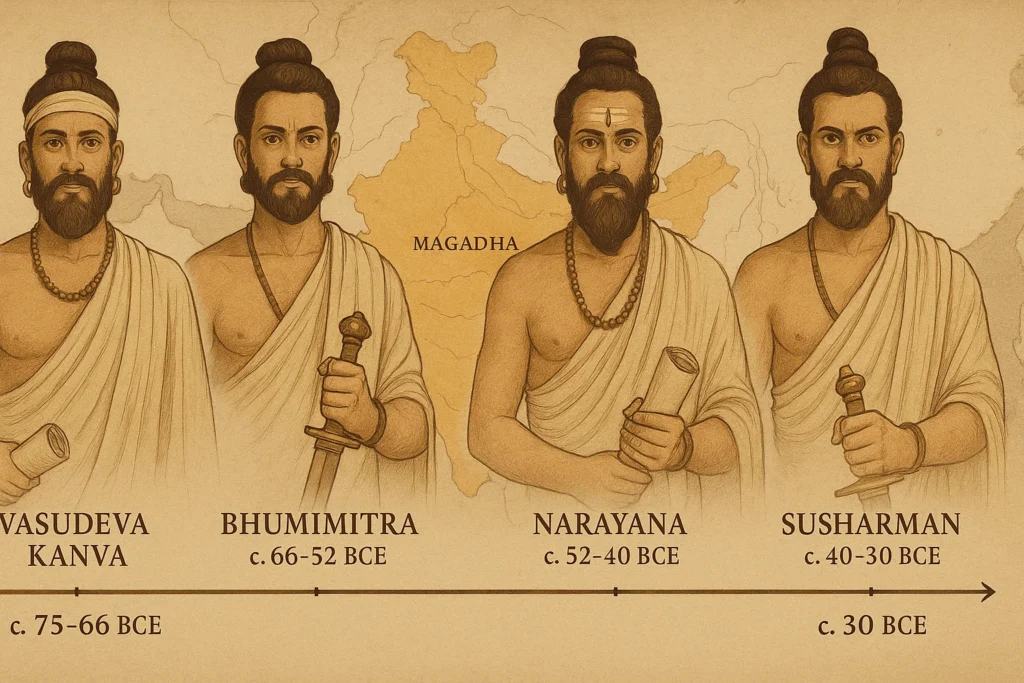

Following Vasudeva’s reign, the Kanva throne passed to three successive rulers. Unfortunately, due to the lack of contemporary inscriptions or detailed chronicles, much of what we know about these kings comes from Puranic literature, which offers skeletal biographies but valuable chronological insight.

1. Bhumimitra

Bhumimitra, the son of Vasudeva, ascended the throne and continued to uphold the administrative and religious framework established by his father. His reign is estimated to have lasted for approximately 14 years. While there is little concrete evidence of military or administrative achievements, his rule likely emphasized the continuation of Brahmanical governance and stability in the post-Shunga context. Puranic texts mention his name with a tone of continuity, suggesting he maintained the dynasty’s established order without major disruption.

2. Narayana

The next ruler was Narayana, believed to be the son or grandson of Bhumimitra. His reign lasted around 12 years, and like his predecessor, he is a shadowy figure in historical texts. The limited references suggest that Narayana’s reign was marked by a gradual decline in central power, possibly challenged by rising regional forces such as the Satavahanas in the Deccan.

3. Susharman

Susharman, the last known ruler of the Kanva line, ruled for around 10 years. His tenure marked the final phase of Kanva rule, which ended when Satakarni II of the Satavahana Dynasty overthrew him and brought Magadha under Deccan control around 30 BCE. This event signifies not only the end of the Kanva line but also the northward expansion of the Satavahanas, symbolizing the shift of political power from the Gangetic plains to the southern territories.

Timeline of the Kanva Dynasty

| Ruler | Approx. Years of Reign | Key Contributions / Events |

| Vasudeva Kanva | c. 75 – 66 BCE | Founder, ended Shunga rule, legitimized power through Brahmanism |

| Bhumimitra | c. 66 – 52 BCE | Son of Vasudeva, ensured political continuity |

| Narayana | c. 52 – 40 BCE | Possibly grandson of Vasudeva, weaker central authority |

| Susharman | c. 40 – 30 BCE | Last ruler, defeated by Satavahana king Satakarni II |

The political history of the Kanva Dynasty reveals a unique chapter in ancient India where courtly intelligence, Brahmanical influence, and religious legitimacy outweighed military might. While their reign was short and sparsely documented, the Kanva rulers maintained stability during a volatile era and preserved Vedic traditions in a rapidly transforming Indian subcontinent. Their decline, followed by the rise of the Satavahanas, marks an important geographical and cultural shift of power from the Indo-Gangetic plains to the Deccan plateau, setting the stage for the next phase in Indian history.

Administration and Governance of the Kanva Dynasty

The Kanva Dynasty, though brief in its reign (c. 75 BCE – 30 BCE), functioned as a stabilizing force in a transitional era of Indian history. While much of its administrative framework remains elusive due to a lack of inscriptions or detailed contemporary records, a careful examination of Puranic sources, historical patterns, and continuity from earlier dynasties reveals valuable insights into the governance model, Brahmanical ideology, and military approach of this lesser-known dynasty.

Structure of Governance: Continuity from Shunga Practices

The administrative structure of the Shungas, who in turn adopted the decentralized yet effective patterns of the Mauryan Empire, was essentially passed down to the Kanvas. Given that Vasudeva Kanva himself was a minister in the Shunga court, his understanding of bureaucratic systems allowed for a smooth transition with minimal disruption to governance.

Key features of the Kanva administrative structure likely included:

- Provincial governance, where local governors (rajukas or amatyas) managed revenue collection, law, and order.

- Royal advisory councils, comprising ministers, Brahmanical scholars, and military officials, continued to function as a guiding body.

- Urban administration in key centers like Pataliputra focused on trade, religious institutions, and law enforcement, regulated through guilds and regional authorities.

This continuity ensured that the basic functions of the state—taxation, justice, defense, and public order—remained stable even amid dynastic shifts.

Brahmanical Influence and Patronage

One of the defining aspects of Kanva rule was its deep entrenchment in Brahmanical ideology. Unlike the Mauryas, who supported multiple religions including Buddhism and Jainism, and even the Shungas, who were known for occasional persecution of Buddhists, the Kanvas firmly positioned themselves as guardians of Brahmanism.

As Brahmins by birth, the Kanva rulers drew political legitimacy from their religious identity. They patronized:

- Vedic rituals, yagnas, and orthodox priestly activities.

- Temples and religious scholars, encouraging a revival of Sanskrit literature and traditional dharmashastra-based legal systems.

- Educational institutions like gurukulas, which may have flourished under their protection.

This patronage was not merely symbolic—it also reinforced the caste-based social hierarchy and religious authority of the Brahmins, helping consolidate Kanva power among the traditional elites.

Their reputation as the innate keepers of dharma (just governance) was further reinforced by the fact that the dynasty’s name, “Kanva,” was derived from a venerated Vedic sage and clan. Their rule signaled a political environment where religion and governance were inseparably linked, reflecting a broader pattern of ideological consolidation in post-Mauryan India.

Military and Diplomatic Policies

The Kanvas did not rule an expansive empire, nor are they known for large-scale conquests. Instead, their military strategy appeared to focus on defensive stability and regional control, particularly around the Gangetic heartland. However, they did inherit a modest standing army from the Shungas, which they likely used to maintain internal order and defend against minor frontier threats.

Key observations about their military and diplomacy include:

- Limited military expansion: Unlike the Mauryas, whose campaigns stretched across the subcontinent, the Kanvas did not pursue aggressive territorial ambitions.

- Internal security: With a relatively small kingdom, they focused on quelling internal dissent and guarding strategic cities such as Pataliputra.

- Diplomatic challenges: The Kanvas may have faced pressure from rising powers, notably the Satavahanas in the Deccan, who would eventually end their rule. There’s no significant record of alliances or treaties, suggesting either limited diplomatic outreach or gaps in surviving records.

While the lack of surviving inscriptions prevents a full understanding of their military apparatus, the fall of the dynasty to Satakarni II of the Satavahanas around 30 BCE suggests that the Kanva military was either weakened by internal decay or outmaneuvered by a stronger and more organized rival.

The Kanva Dynasty’s administrative model was a product of continuity, adaptation, and religious ideology. By preserving Shunga-era institutions, aligning closely with Brahmanical orthodoxy, and maintaining a defensive military posture, the Kanvas offered a semblance of order in a period of political fragmentation. Their reign exemplifies how religious legitimacy could substitute for military expansion as a source of authority in ancient India, marking a unique chapter in the evolution of Indian statecraft.

Cultural and Religious Contributions of the Kanva Dynasty

Despite ruling for only a brief period—from approximately 75 BCE to 30 BCE—the Kanva Dynasty played a crucial role in reinforcing the Brahmanical cultural revival in post-Mauryan India. Though archaeological and literary evidence from their reign is sparse, their contributions can be inferred through historical continuity, textual references, and the religious-political milieu of the era. Their rule represents a significant phase in the reshaping of Indian cultural identity, where religious orthodoxy and statecraft became deeply interlinked.

Patronage of Brahmanism and Sanskrit Traditions

The Kanva monarchs considered themselves the defenders of Vedic culture and orthodoxy, as they were Brahmins by caste and thought. In contrast to the more eclectic religious patronage of the Mauryan Empire, which included Buddhism and Jainism, the Kanvas deliberately positioned Brahmanism as the ideological backbone of their governance.

Their cultural contributions centered on the following key areas:

- Revival of Vedic rituals and practices: The Kanvas actively promoted sacrificial rites (yajnas), ceremonial worship, and the priestly class’s authority, reinforcing the varna system and Brahmanical codes of conduct.

- Support for Sanskrit scholarship: Although no specific texts are attributed directly to Kanva patronage, the continued development of Sanskrit literature during this time suggests a conducive environment for grammarians, theologians, and poets aligned with Brahmanical traditions.

- Promotion of Dharmashastra principles: Legal and social codes rooted in Brahmanical texts likely gained further influence under Kanva rule, shaping the conduct of individuals and communities according to Vedic law.

By embracing religious orthodoxy as state policy, the Kanvas contributed to the cultural continuity of ancient India, especially during a period when regional powers were beginning to assert independent identities and spiritual philosophies.

Temples, Inscriptions, or Literature: Scarcity of Material Evidence

Unlike the Mauryas and later Satavahanas, the Kanvas have left behind very limited direct archaeological or epigraphic evidence. No surviving temples, inscriptions, or courtly texts have been definitively attributed to their dynasty, which presents a challenge for historians.

However, this absence should not be mistaken for a lack of cultural impact. Several factors can explain the paucity of material remains:

- Short duration of the dynasty: With just over four decades of rule and frequent succession changes, the Kanvas may not have had the stability or resources to commission monumental works.

- Later destruction or assimilation: Many possible cultural artifacts may have been destroyed or absorbed by succeeding dynasties, particularly the Satavahanas, who overtook Kanva territories.

- Oral transmission of traditions: Like much of early Brahmanical knowledge, Kanva-era cultural contributions may have persisted through oral transmission rather than written or inscribed form.

Even in the absence of tangible monuments, the continuation and reinforcement of Vedic traditions during their rule had a lasting influence on the religious fabric of ancient India.

Coexistence with Other Religions, Especially Buddhism

While the Kanvas were unapologetically Brahmanical in their orientation, there is no concrete evidence to suggest that they persecuted other religions, such as Buddhism, which was still influential in eastern India during their reign.

In fact, the Indian subcontinent during this period was marked by religious pluralism, where:

- Buddhist monasteries (viharas) continued to operate in regions adjacent to Kanva territories.

- Trade networks, which often supported Buddhist merchants and monks, remained active across central and eastern India.

- Coexistence, rather than conflict, seems to have been the norm, particularly because the Kanvas lacked the imperial reach to impose religious hegemony across vast areas.

This environment of cohabitation, even if Brahmanism enjoyed state preference, reflects the resilience and adaptability of Indian spiritual traditions, which often evolved side by side rather than in opposition.

Moreover, it is worth noting that Pataliputra, the political center during Kanva rule, remained a multi-religious hub, where Brahmins, Buddhists, Jains, and other sects engaged in philosophical debates, scholarship, and social dialogue.

Although the Kanva Dynasty’s cultural and religious footprint is not well-documented through inscriptions or grand monuments, their historical role as promoters of Brahmanical orthodoxy and Sanskrit learning is undeniable. By reviving Vedic traditions and reinforcing the social order based on Brahmanical values, they laid the groundwork for the religious and cultural policies that would be continued by later dynasties in northern and central India. Their rule may have been short, but it served as a bridge between the Shunga emphasis on ritualism and the Satavahana embrace of pluralistic patronage, helping to preserve and transmit a significant chapter in India’s spiritual and cultural evolution.

Decline and Fall of the Kanva Dynasty

The Kanva Dynasty, despite its efforts to maintain administrative continuity and religious orthodoxy, was a short-lived political entity that ruled parts of eastern and central India for roughly 45 years, from c. 75 BCE to 30 BCE. Though its rise to power marked a significant moment in the post-Mauryan transition, the dynasty eventually succumbed to a combination of internal fragility and external aggression. Its downfall was not marked by a single catastrophic event, but by a gradual erosion of authority, culminating in its conquest by the Satavahanas (Andhras).

Internal Weaknesses and Lack of Strong Successors

One of the core reasons behind the decline of the Kanva Dynasty was its inability to produce strong and charismatic successors after its founder, Vasudeva Kanva. While Vasudeva had risen to power through political acumen and religious legitimacy, his successors—Bhumimitra, Narayana, and Susharman—failed to display the same degree of leadership or strategic foresight.

Several key factors contributed to this internal decline:

- Dynastic Fragility: The dynasty lacked a robust structure for succession and governance. With each successive ruler, the central authority weakened, leading to diminishing control over provinces and vassals.

- Political Isolation: Unlike the Mauryans and even the Shungas, the Kanvas did not establish strong alliances with other regional powers. This made them more vulnerable to encroachments.

- Overdependence on Brahmanical Legitimacy: While Brahmanism reinforced their ideological rule, it could not compensate for the lack of military strength or popular support in the face of external threats.

The result was a gradual internal disintegration—administrative inefficiencies, waning loyalty among local governors, and loss of influence in peripheral regions—all of which made the dynasty ripe for conquest.

Invasion by the Satavahanas (Andhras)

The Satavahanas’ ascent to dominance in the Deccan dealt the Kanva Dynasty its fatal blow, not internal insurrection. Also known as the Andhras, the Satavahanas had been growing in strength since the decline of Mauryan power, gradually expanding their influence northward into central and eastern India.

By the end of the Kanva rule, Satakarni II, a prominent Satavahana ruler, launched a successful military campaign that led to the defeat and overthrow of Susharman, the last known Kanva king. This marked not only the end of the Kanvas but also the beginning of Satavahana dominance in the Magadha region—a significant northward shift for a southern dynasty.

The reasons behind the Satavahanas’ success were multi-fold:

- Stronger military organization and a larger territorial base

- Strategic use of diplomacy and marriage alliances to weaken rival states

- Economic strength, backed by control over major trade routes and ports in western and southern India

This conquest allowed the Satavahanas to integrate the culturally rich region of Magadha into their growing empire, blending Deccan and north Indian traditions in the process.

Approximate End of the Dynasty Around 30 BCE

The majority of researchers concur that the Kanva Dynasty ended approximately 30 BCE, while precise dates are up for controversy because there are no inscriptions or modern documents. The final ruler, Susharman, is believed to have been defeated and deposed by Satakarni II, closing the chapter on the Kanva lineage.

The Puranas, which are among the primary sources for this period, confirm a brief four-generation rule of the Kanvas and note the subsequent rise of the Andhras. With the fall of the Kanvas:

- The political center of gravity shifted further south,

- Brahmanical influence began to blend with the more inclusive and diverse religious policies of the Satavahanas,

- And the post-Mauryan fragmentation began transitioning into a new wave of regional kingdoms with stronger economic and military foundations.

The decline and fall of the Kanva Dynasty reflect a broader pattern in ancient Indian history—where political power often passed swiftly between dynasties during periods of regional fragmentation. The Kanvas, despite their religious authority and administrative continuity, failed to build the institutional strength, military capacity, or popular legitimacy necessary to survive in a competitive and evolving geopolitical environment.

Their end, though quiet and largely undocumented, was historically significant—it paved the way for the Satavahana ascendancy and furthered the cultural synthesis of northern and southern Indian traditions. The fall of the Kanvas reminds us that ideological legitimacy must be backed by strategic governance and adaptive leadership, a lesson echoed throughout India’s complex historical landscape.

Legacy and Historical Significance of the Kanva Dynasty

Though often lost in the shadow of their more illustrious predecessors and successors, the Kanva Dynasty holds an important, albeit understated, place in the political and cultural continuum of ancient India. Between the fall of the Shunga Empire and the ascent of the Satavahanas (Andhras), their brief rule—from around 75 BCE to 30 BCE—acted as a transitional period. Far from being a mere historical footnote, the Kanvas contributed to preserving administrative order and religious orthodoxy during a crucial transitional phase in the subcontinent’s evolution.

Transitional Role Between the Shungas and Satavahanas

The fall of the Shunga Empire had left a political vacuum in the Gangetic plains, particularly in Magadha, a region historically regarded as the heart of imperial India. In this fragile context, the Kanva Dynasty stepped in not as conquerors, but as custodians—maintaining continuity in governance, social order, and cultural norms.

Their rule acted as a stabilizing force, preventing fragmentation at a time when India was moving from large centralized empires to regionalized polities. Though they did not embark on territorial expansion or sweeping reforms, their very existence:

- Helped preserve political coherence in northern India

- Provided a cultural and religious counterbalance to the growing influence of southern powers like the Satavahanas

- Served as a buffer period that allowed for a smoother integration of north Indian traditions into the expanding Deccan-based kingdoms

Without the Kanva interlude, the sudden collapse of the Shungas might have led to greater chaos or a more abrupt cultural disjunction.

Why the Kanvas Are Often Overlooked in Mainstream Narratives

Despite their historical importance, the Kanvas have remained largely neglected in mainstream historiography and academic curricula. Several factors contribute to this marginalization:

- Short duration of rule: Lasting only four generations over about 45 years, the Kanvas did not have time to establish enduring institutions or cultural monuments.

- Lack of inscriptions and material evidence: Unlike the Mauryas or Satavahanas, the Kanvas left behind no known stone edicts, inscriptions, or architectural marvels that could anchor them in the archaeological record.

- Overshadowed by powerful dynasties: Their reign is sandwiched between two major powers—the Shungas, who succeeded the Mauryan Empire, and the Satavahanas, who left a lasting impact on Deccan and pan-Indian history. As a result, the Kanvas often appear as a minor footnote in historical texts.

- Reliance on Puranic sources: Much of what we know about the Kanvas comes from later Puranic texts, which offer limited and sometimes ambiguous information, leading some historians to underestimate their role.

This lack of visibility, however, should not obscure the fact that the Kanvas played a critical transitional and preservational role in a period marked by uncertainty and change.

Their Role in the Continuity of Vedic Traditions in the North

One of the most enduring legacies of the Kanva Dynasty lies in its unwavering support for Brahmanism and Vedic traditions. At a time when Buddhism and Jainism were gaining significant ground in various regions, the Kanvas, as Brahmins-turned-kings, took it upon themselves to reinforce Vedic orthodoxy and ensure its dominance in the religious and cultural fabric of northern India.

Their contributions included:

- Revival of Vedic rituals and yajnas, often under royal patronage

- Promotion of Sanskrit language and Brahmanical scholarship

- Strengthening of caste-based social order as prescribed in Dharmashastra texts

By institutionalizing these practices, the Kanvas laid the foundation for the resurgence of Brahmanical dominance, which would later be adopted and adapted by many future dynasties, including the Guptas.

Moreover, their emphasis on religious conservatism over expansionist militarism served as a counter-narrative to the more pluralistic and dynamic religious trends elsewhere, thereby maintaining a core zone of Brahmanical influence in the Indo-Gangetic plains.

The Kanva Dynasty’s true significance lies not in conquest or architectural grandeur, but in continuity—of governance, culture, and religion—during one of ancient India’s most transitional periods. Often overlooked due to their modest achievements and lack of surviving monuments, the Kanvas nonetheless preserved the ideological and administrative threads that tied together the Mauryan legacy and the regional empires that followed. Their reign reminds us that in history, not every important dynasty is remembered for what it built—some are vital for what they preserved.

Archaeological and Literary Sources of the Kanva Dynasty

Reconstructing the history of the Kanva Dynasty poses a formidable challenge for historians and scholars. Unlike the Mauryas or the Guptas, the Kanvas did not leave behind an extensive corpus of inscriptions, coins, or monuments. As a result, much of what is known about this brief yet transitional dynasty comes from literary references, particularly the Puranas, combined with limited archaeological evidence—most notably, a remarkable inscription that links the dynasty to early Krishna worship.

Puranas and Ancient Texts as Primary Sources

The Puranas, composed and compiled over several centuries, serve as the chief literary source for the history of the Kanva Dynasty. These ancient Hindu texts—especially the Vayu Purana, Matsya Purana, and Brahmanda Purana—offer genealogical lists, approximate regnal years, and dynastic transitions. They talk of the ascent of Vasudeva Kanva, his successors, and the Andhras’ (Satavahanas’) final takeover of the dynasty.

Although the Puranas are not historical records in the modern sense, they provide valuable context regarding:

- The succession of rulers (Vasudeva, Bhumimitra, Narayana, and Susharman)

- The approximate timeline of the dynasty (c. 75 BCE – 30 BCE)

- The religious and cultural landscape of the time

Other ancient texts, including Buddhist and Jain literature, are largely silent about the Kanvas, possibly due to their strong Brahmanical orientation, which did not resonate with those religious traditions.

Limitations of Evidence and Gaps in Historiography

One of the least well-documented royal dynasties in ancient Indian history is the Kanva Dynasty. This scarcity of records is due to several factors:

- Short duration of rule (approximately 45 years), offering limited time to commission inscriptions or construct enduring monuments.

- Lack of royal edicts or coinage attributed definitively to the Kanva rulers, making it difficult to trace their territorial influence and economic policies.

- Reliance on religious texts like the Puranas, which often blur the line between myth and historical fact.

These limitations have contributed to a fragmented and speculative historiography, where much of the Kanva legacy is reconstructed through interpretive analysis rather than direct evidence.

Interpretation Challenges for Historians

Historians face multiple challenges in interpreting the Kanva period due to the nature of available sources:

- Chronological Uncertainty: Puranic texts often offer conflicting regnal years and are silent on key events or policies of individual rulers.

- Religious Bias: As Brahmanical texts, the Puranas may exaggerate or downplay certain facts to align with religious ideals, affecting the objectivity of historical reconstruction.

- Absence of Contemporary Records: With no court chronicles or administrative documents surviving, historians must depend on later interpretations and cross-cultural references.

Despite these challenges, one unique piece of archaeological evidence offers a rare and fascinating window into the cultural milieu of the Kanva era.

The Heliodorus Pillar: A Singular Archaeological Link

One of the most compelling artifacts associated with the Kanva period is the Heliodorus Pillar, also known as the Garuda Pillar, located at Besnagar (modern-day Vidisha, Madhya Pradesh). Erected during the reign of Vasudeva Kanva, this inscription stands out not only for its craftsmanship but for its cross-cultural and religious significance.

The Greek diplomat Heliodorus was dispatched to the Kanva court by Antialcidas, the monarch of Taxila, during Vasudeva’s reign. Profoundly influenced by Indian spiritual philosophy, Heliodorus embraced Vaishnavism and commissioned a commemorative pillar dedicated to Lord Vasudeva (Krishna). Inscribed in Brahmi script and dating back to around 113 BCE, the monument bears the following declaration:

“This Garuda pillar of Vasudeva, the God of gods, was erected by Heliodorus, the Bhagavata, the son of Dion, a Greek ambassador from Taxila.”

This inscription is significant for several reasons:

- It is the earliest known archaeological evidence of Bhagavata (Krishna) worship.

- It demonstrates the cross-cultural interactions between Indian and Indo-Greek civilizations during the Kanva era.

- It provides rare contemporaneous material proof of Vasudeva Kanva’s rule and influence.

- It validates the presence of Krishna worship as early as the 2nd century BCE, making it a cornerstone in the study of early Vaishnavism.

While the Heliodorus Pillar is not a direct Kanva royal edict, its association with the Kanva court underscores the dynasty’s indirect role in fostering early Vaishnavite devotion and intercultural diplomacy.

The Kanva Dynasty remains an enigma in Indian history—a dynasty preserved more in scripture than in stone. The Puranic texts, despite their inconsistencies, serve as crucial narrative sources, while the Heliodorus Pillar stands as the sole archaeological beacon, shedding light on the religious and diplomatic environment of the period.

For historians, the Kanva period represents a puzzle of gaps and fragments, yet within those fragments lie valuable insights into how ancient India negotiated dynastic transitions, spiritual diversity, and foreign engagement. The challenge now lies in reinterpreting these limited sources with care, context, and scholarly rigor, continuing the effort to bring the Kanvas out of obscurity and into the larger conversation on India’s civilizational legacy.

Comparative Perspective: The Kanva Dynasty in Context

To understand the historical significance of the Kanva Dynasty, it is essential to view it in comparison with its predecessor, the Shunga Dynasty, and its successor, the Satavahana Dynasty. These three powers collectively shaped the political, religious, and cultural transitions in post-Mauryan India (c. 185 BCE to 200 CE), each contributing distinct elements to the subcontinent’s evolving civilizational fabric.

Kanva vs. Shunga and Satavahana Dynasties

Political Trajectory and Governance

- Shungas: The Shunga Dynasty (c. 185–75 BCE), established by Pushyamitra Shunga after overthrowing the Mauryan emperor Brihadratha, was a militarily assertive and expansionist regime. It actively resisted foreign invasions (such as the Indo-Greeks) and promoted central authority, particularly in the Gangetic heartland.

- Kanvas: In contrast, the Kanva Dynasty (c. 75–30 BCE) emerged not through conquest but through courtly coup. Their government, which was established by Brahmin minister Vasudeva Kanva, was more conservative and modest, emphasizing the preservation of religious orthodoxy and internal order over territorial development. The Kanvas governed largely through inherited Shunga administrative frameworks.

- Satavahanas: In the Deccan, the Andhras, also known as the Satavahana Dynasty (c. 1st century BCE–3rd century CE), were a major regional force. They established a powerful, trade-driven empire that encouraged governmental decentralization, marine trade, and cultural fusion after defeating the Kanvas. Local autonomy was tempered with imperial control under their governance.

Key Contrast: While the Shungas and Satavahanas emphasized military and regional expansion, the Kanvas served as a transitional and stabilizing force, lacking both the imperial ambition of the Shungas and the administrative depth of the Satavahanas.

Religious Patronage and Ideological Orientation

- Shungas: The Shungas were staunch Brahmanical revivalists, often accused of opposing Buddhism (e.g., the controversial claim of destroying Buddhist stupas). They revived Vedic rituals, such as the Ashvamedha sacrifice, and aimed to restore priestly dominance after the more inclusive Mauryan rule.

- Kanvas: Being Brahmins by caste, the Kanvas carried on and expanded upon the Shungas’ Brahmanical orthodoxy. However, they appear to have coexisted more peacefully with other sects, including early Vaishnavism and Buddhism. Notably, during Vasudeva Kanva’s reign, the Greek ambassador Heliodorus erected a pillar in honor of Lord Krishna, suggesting a broader spiritual inclusivity despite Brahmanical dominance.

- Satavahanas: The Satavahanas approached religion in a diverse manner. While many of their rulers were Brahmanical and performed Vedic rituals, they also patronized Buddhism, sponsoring the construction of cave monasteries (like those at Ajanta and Nasik) and supporting Buddhist relic worship.

Key Contrast: The Shungas and Kanvas both promoted Brahmanical traditions, but the Satavahanas displayed a more balanced and inclusive religious policy, fostering cultural pluralism across their domains.

Cultural Contributions and Legacy

- Shungas are remembered for revitalizing Indian art and literature, especially through the early development of Sanskrit drama and sculptural traditions. The Bharhut and Sanchi stupas were enhanced under their rule.

- Kanvas, though they ruled from the cultural heartland of Pataliputra, left behind very few monuments or texts. However, their rule preserved Vedic traditions, and the Heliodorus Pillar from the Kanva era remains one of the earliest known archaeological testimonies of Krishna worship.

- The Satavahanas were frequent buyers of inscriptions, artwork, and buildings. They promoted Prakrit language inscriptions, contributed to the rise of rock-cut architecture, and supported merchant guilds that financed religious institutions.

Key Contrast: The Kanvas played more of a preservationist role, whereas the Shungas and Satavahanas actively contributed to cultural innovation and infrastructure development.

Broader Impact on Indian Polity and Religion in the Post-Mauryan Era

The post-Mauryan period was characterized by the fragmentation of centralized imperial authority and the emergence of regional dynasties. The Kanvas, Shungas, and Satavahanas were each instrumental in navigating this transformation.

- Political Decentralization: All three dynasties contributed to the shift from a Mauryan-style unitary empire to a mosaic of regional powers. The Kanvas, by maintaining inherited structures and avoiding overreach, helped ensure a relatively smooth political transition, which the Satavahanas then capitalized on to expand their influence northward.

- Religious Realignment: These dynasties played vital roles in reshaping India’s religious topography:

- The Shungas laid the groundwork for Brahmanical resurgence.

- The Kanvas deepened this Vedic emphasis while preserving space for early Vaishnavism.

- The Satavahanas harmonized Brahmanism and Buddhism, shaping the religious coexistence that would define much of India in the early centuries CE.

- Cultural Synthesis: Together, these dynasties reflected a period of cultural negotiation, where Indo-Greek influences, regional artistic styles, and linguistic diversity merged into a dynamic civilizational landscape. The Kanvas’ ideological conservatism balanced the innovation seen under other powers, ensuring continuity amidst transformation.

The Kanva Dynasty, when viewed in comparative perspective, emerges not as a mere interlude but as a critical transitional force in Indian history. Bridging the assertive Shungas and the expansive Satavahanas, the Kanvas helped stabilize northern India during a politically sensitive era and safeguarded Vedic traditions at a time of ideological flux. While they lacked the cultural flamboyance or imperial reach of their counterparts, their rule was vital in preserving the intellectual and religious continuity of the Indo-Gangetic civilization—a role often underappreciated, but no less significant.

Conclusion & FAQs

The Kanva Dynasty, though often overshadowed by the grandeur of the Mauryas, Guptas, and Satavahanas, served as a silent yet significant bridge in India’s historical continuum. Ruling from around 75 BCE to 30 BCE, the Kanvas maintained administrative continuity between the fall of the Shungas and the rise of the Satavahanas, especially in Magadha, the core of ancient Indian power. The dynasty, which was established by the Brahmin minister turned king Vasudeva Kanva, emphasized the growing interdependence of religion and politics by promoting early Vaishnavism and preserving Brahmanical customs, as demonstrated by the renowned Heliodorus Pillar.

Although they left behind no grand monuments or conquests, their legacy lies in preserving civilizational threads during a time of political flux. Studying dynasties like the Kanvas helps us move beyond empire-centric histories and appreciate the understated yet essential roles played by regional powers. These “silent chapters” of Indian heritage enrich our understanding of the past and remind us that continuity and preservation are as vital to history as expansion and innovation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Who founded the Kanva Dynasty?

The Kanva Dynasty was founded by Vasudeva Kanva, a Brahmin minister in the court of the last Shunga king, Devabhuti. Vasudeva overthrew Devabhuti and established his rule around 75 BCE.

What was the duration of the Kanva Dynasty’s rule?

The Kanva Dynasty ranks among the briefest regimes in ancient Indian history, enduring for merely 45 years—from approximately 75 BCE to 30 BCE.

Why is the Kanva Dynasty significant?

Despite its brevity, the Kanva Dynasty served as a transitional power between the Shungas and the Satavahanas. It preserved Brahmanical traditions, stabilized Magadha, and played a role in the early promotion of Vaishnavism, as seen in the Heliodorus Pillar inscription.

What are the main sources of information about the Kanva Dynasty?

Information about the Kanvas comes mainly from the Puranas and other ancient literary texts. The Heliodorus Pillar at Besnagar is a key archaeological artifact associated with their reign, offering rare evidence of Indo-Greek and early Krishna worship during that era.

How did the Kanva Dynasty come to an end?

The Kanvas were overthrown around 30 BCE by the rising Satavahana Dynasty. The last Kanva ruler, Susharman, was likely defeated by Satakarni II, signaling the end of Kanva rule and the beginning of Satavahana expansion into northern India.

What was the Kanva Dynasty’s religious policy?

The Kanvas were staunch supporters of Brahmanism. They promoted Vedic rituals, caste hierarchy, and Brahminical authority, though evidence also suggests tolerance towards other faiths, particularly Vaishnavism.

Why is the Heliodorus Pillar important?

The Heliodorus Pillar, erected by a Greek ambassador during Vasudeva Kanva’s reign, is the earliest known archaeological evidence of Krishna worship. It symbolizes the cross-cultural spiritual exchange between Indo-Greek and Indian traditions.