Introduction

Brief Overview of the Mauryan Empire

The Mauryan Empire, founded by Chandragupta Maurya in 321 BCE, was one of the most powerful and extensive empires in ancient Indian history. Spanning large parts of the Indian subcontinent, it stretched from the Himalayas in the north to the Deccan Plateau in the south, and from the eastern boundary of Bengal to the western reaches near present-day Iran. At its zenith, the Mauryan Empire became a beacon of political unity, economic prosperity, and cultural vibrancy. Under the leadership of Chandragupta Maurya, and later his grandson Emperor Ashoka, the empire implemented innovative governance systems and promoted trade, infrastructure, and the spread of Buddhism.

Significance of the Mauryan Empire in Indian History

The Mauryan Empire holds a unique place in Indian history as the first empire to unify most of the Indian subcontinent under a centralized authority. Its significance lies not only in its territorial extent but also in its administrative advancements, economic development, and cultural contributions. The Mauryan administration set a precedent for future empires with its efficient bureaucracy, a well-structured civil service, and a network of provincial governors. The economy flourished through regulated trade, standardized coinage, and the construction of roads and infrastructure that facilitated commerce and communication.

One of the Mauryan Empire’s most lasting contributions is its pivotal role in advancing Buddhism, particularly under the leadership of Ashoka. Following the devastating Kalinga War, Ashoka’s conversion to Buddhism marked a significant turn towards advocating for non-violence and ethical leadership. His commitment to these principles was evident in his support for Buddhism, which extended far beyond India’s borders. The edicts he carved into stone pillars and rocks offer a window into the moral and societal values of his era, highlighting themes of compassion, tolerance, and public welfare.

Transition from Fragmented Kingdoms to the First Large-Scale Empire in India

Before the rise of the Mauryan Empire, the Indian subcontinent was a patchwork of regional kingdoms, each vying for dominance. The political landscape was characterized by fragmentation, with powerful dynasties like the Nandas in Magadha, the Avanti in central India, and the Kalingas in the east controlling separate regions. These rivalries often led to instability, hindering any large-scale unity or development.

The emergence of Chandragupta Maurya, guided by the astute political strategist Chanakya (Kautilya), marked a decisive turning point. Chandragupta’s conquest of the Nanda dynasty in Magadha laid the foundation for the Mauryan Empire. Over time, through a mix of military conquest, diplomacy, and strategic alliances, the Mauryan rulers brought vast and diverse regions under one central authority. This transition was not merely about territorial acquisition; it represented the establishment of a new political order, one based on centralized governance, codified laws, and an empire-wide bureaucracy.

The Mauryan Empire’s success in consolidating such a vast and culturally diverse region into a cohesive political entity was unprecedented. It laid the groundwork for future empires to build upon, demonstrating that a unified Indian subcontinent was achievable and sustainable. The rise of the Mauryan Empire thus marks a defining chapter in Indian history, transitioning from fragmented regional rule to a centralized empire with a lasting influence on governance, culture, and ideology across South Asia.

Foundation and Early Rise of the Mauryan Empire

Chandragupta Maurya: Founder of the Mauryan Empire

Chandragupta Maurya is a towering figure in Indian history, recognized as the visionary founder of the Mauryan Empire, which he established in 321 BCE. Rising from modest origins, Chandragupta’s ascent from anonymity to emperor is a compelling story marked by ambition, determination, and astute strategy. Historical accounts, including those from ancient texts like the Arthashastra and writings of Greco-Roman historians, suggest that he was born into a modest family, possibly in the region of present-day Bihar or eastern Uttar Pradesh.

Chandragupta’s ascent to power started with his decisive move to confront the Nanda dynasty, a formidable yet widely disfavored regime that dominated the Magadha region. Under his leadership, the Mauryan army expanded rapidly, using a combination of military might and political alliances. By establishing a centralized and efficient administrative structure, Chandragupta laid the foundation for what would become one of the largest and most influential empires in Indian history. His reign marked the beginning of an era characterized by political stability, economic growth, and significant cultural advancements.

Role of Chanakya (Kautilya) in the Empire’s Establishment

The role of Chanakya, also known as Kautilya or Vishnugupta, was pivotal in the establishment of the Mauryan Empire. An astute scholar, economist, and political strategist, Chanakya was not only the guiding force behind Chandragupta’s rise but also the chief architect of the empire’s governance system. His pivotal work, Arthashastra, acts as a detailed manual on governance, economic strategy, military planning, and statecraft, encapsulating the fundamental principles that defined the Mauryan administration.

Legend has it that Chanakya, driven by a personal vendetta against the Nanda rulers, sought out and mentored Chandragupta, recognizing the young prince’s potential to overthrow the corrupt regime. Chanakya’s meticulous planning and strategic brilliance helped Chandragupta rally forces and gain the support of local chieftains and disillusioned subjects. He employed clever diplomacy, espionage, and calculated alliances to weaken the Nandas’ grip on power.

Beyond the initial conquests, Chanakya played a crucial role in shaping the governance model of the Mauryan Empire. The centralized administrative structure, efficient tax collection systems, and emphasis on internal security and economic development were largely influenced by Chanakya’s principles. His guidance ensured that the Mauryan state was not only expansive but also stable, with a focus on law, order, and welfare that would become a model for subsequent rulers in Indian history.

The Overthrow of the Nanda Dynasty and Consolidation of Power

The overthrow of the Nanda dynasty marked a significant turning point in ancient Indian history. The Nandas, who had ruled Magadha prior to Chandragupta’s rise, were known for their vast wealth and powerful army but were also notorious for their oppressive and authoritarian rule. The last ruler of the dynasty, Dhana Nanda, was widely disliked due to his heavy taxation and unpopular policies, creating a fertile ground for rebellion.

Chandragupta, with the strategic guidance of Chanakya, launched a series of well-planned attacks on the Nanda regime. The precise details of these campaigns remain unclear, but historical sources suggest that Chandragupta’s forces employed guerrilla tactics, sieges, and psychological warfare to destabilize the Nandas. After a protracted struggle, Chandragupta successfully overthrew Dhana Nanda and took control of Pataliputra (modern-day Patna), the capital of Magadha, around 321 BCE.

The consolidation of power did not end with the defeat of the Nandas. Chandragupta faced the daunting task of bringing numerous independent kingdoms and tribal territories under a centralized authority. He rapidly expanded the Mauryan domain through both conquests and alliances, creating a vast empire that stretched across northern and central India. To maintain control, Chandragupta established a sophisticated administrative system, with a hierarchy of governors, local officials, and spies to ensure efficient governance.

The consolidation of power under Chandragupta Maurya was a critical achievement, transforming the fragmented political landscape of the Indian subcontinent into a unified entity. His success laid the groundwork for the future prosperity of the Mauryan Empire, which would reach its zenith under his successors, particularly Ashoka. The strategic brilliance of Chandragupta, coupled with Chanakya’s vision, set in motion a golden era of Indian civilization, characterized by unprecedented political unity, economic strength, and cultural development.

Territorial Expansion and Administration

Conquest and Unification of Northern India

One of the defining features of the Mauryan Empire was its extensive territorial expansion, particularly under Chandragupta Maurya. After overthrowing the Nanda dynasty and seizing control of Magadha, Chandragupta embarked on a series of military campaigns aimed at unifying northern India. This was a monumental achievement considering the fragmented and diverse political landscape of the region, which was composed of various independent kingdoms, tribal states, and republics.

Chandragupta’s most notable conquests included regions such as the Punjab, present-day Uttar Pradesh, and parts of the Deccan Plateau. The annexation of these regions brought under control important trade routes, fertile agricultural lands, and key urban centers, which were critical for the empire’s economic growth. The unification of these territories also marked a shift from a collection of independent polities to a centralized imperial authority, laying the foundation for the first truly pan-Indian empire.

Chandragupta’s military success was not solely based on brute force; it was also due to his adept use of diplomacy and strategic alliances. He utilized a well-trained standing army, coupled with local auxiliaries, and incorporated conquered territories into the empire by allowing regional elites to retain a degree of autonomy in exchange for loyalty. This integration of different regions, cultures, and political systems under one administrative umbrella made the Mauryan Empire a model of governance in the ancient world.

Key Military Campaigns and Diplomatic Alliances

The Mauryan Empire’s expansion was characterized by both strategic military campaigns and shrewd diplomacy. One of the most significant military achievements during Chandragupta’s reign was the confrontation with the successors of Alexander the Great, particularly Seleucus I Nicator, the founder of the Seleucid Empire. In a series of battles around 305 BCE, Chandragupta’s forces successfully resisted Seleucus’s attempts to reclaim the territories in northwestern India that Alexander had once conquered. A historic pact that brought an end to the struggle was a monument to Chandragupta’s skill as a diplomat.

Under the terms of the agreement, Seleucus ceded vast territories, including parts of modern-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran, to the Mauryan Empire. In return, Chandragupta gave Seleucus 500 war elephants, which were later crucial in Seleucid campaigns in the west. This alliance was solidified by a marriage treaty and marked the beginning of cordial diplomatic relations between the Mauryan and Seleucid empires. As part of the diplomatic exchange, Seleucus sent the Greek ambassador Megasthenes to the Mauryan court, whose accounts provide valuable insights into the governance and culture of the empire.

The Mauryan strategy was not limited to military conquest. Diplomacy, marriages, and alliances played a key role in consolidating power and extending the empire’s influence without constant warfare. This balanced approach to expansion allowed the empire to integrate diverse regions while maintaining stability and unity across its vast domain.

Role of Bindusara in Maintaining the Empire

After Chandragupta’s abdication and decision to embrace Jainism, his son Bindusara ascended the throne around 297 BCE. Though frequently eclipsed by the accomplishments of his father and the renowned Ashoka, Bindusara was instrumental in preserving the expansive empire and advancing its territorial growth. Known as “Amitraghata” (the slayer of enemies), Bindusara continued his father’s policies of conquest and consolidation, extending the empire further into the Deccan Plateau.

Bindusara’s reign was characterized by relative internal stability and the further strengthening of central control. Unlike Chandragupta, who focused on unification and initial expansion, Bindusara concentrated on consolidating the newly acquired territories and maintaining the administrative structure. He maintained good diplomatic relations with neighboring states, including the Hellenistic world, and ensured that the empire’s extensive trade networks remained intact.

One of Bindusara’s significant achievements was the extension of the Mauryan Empire into southern India. He led campaigns that brought much of the Deccan region under Mauryan control, though the far southern tip of the Indian peninsula remained outside the empire’s reach. Through these campaigns, Bindusara not only expanded the territorial boundaries but also integrated diverse cultures and economies into the Mauryan administrative framework.

Administratively, Bindusara is credited with maintaining the bureaucratic efficiency established by his father. The empire was divided into provinces, each governed by a royal prince or trusted official. These provinces were further subdivided into districts and villages, ensuring effective governance and efficient tax collection. The centralized administration, supported by a network of spies and local officials, allowed the empire to function smoothly even across vast and culturally diverse territories.

Bindusara’s rule, while less documented than those of Chandragupta and Ashoka, was crucial in maintaining the stability and continuity of the Mauryan Empire. His successful administration provided a solid foundation for his son, Ashoka, to inherit a strong, unified empire and eventually transform it into one of history’s most celebrated reigns.

Administration and Governance

The Mauryan Empire, spanning from 321 BCE to 185 BCE, was distinguished by its highly organized and efficient administrative system, which set the standard for governance in ancient India. The empire’s administrative model was crucial in managing its vast territories, diverse populations, and complex economies. The system combined centralized authority with a network of provincial and local governance, ensuring that policies were effectively implemented across the empire.

Political Structure

- Centralized Government System: The Mauryan Empire was one of the earliest examples of a highly centralized government in India. At the top of the hierarchy was the emperor, who held absolute power over political, military, and economic affairs. The emperor was regarded as a divine representative, embodying both secular authority and moral responsibility. The central government was headquartered in Pataliputra (modern-day Patna), which served as the nerve center for the administration. From here, imperial edicts, laws, and policies were disseminated throughout the empire.

- Provinces and Local Governance: The empire was divided into several provinces (known as janapadas), each governed by a royal prince, or a trusted official known as a kumara or rajuka. These provincial governors were responsible for maintaining law and order, collecting revenue, and administering justice within their territories. The provinces were further divided into districts (vishayas) and villages (gramas), each with its own local administration. This multi-tiered structure allowed for efficient governance while also giving some degree of autonomy to local authorities, ensuring that regional differences were respected.

- Role of Ministers and Advisors: A council of ministers, known as the Mantri parishad, advised the emperor on matters of state, military strategy, and economic policy. Among these advisors, Chanakya (Kautilya) was the most notable during Chandragupta Maurya’s reign. The ministers were experts in various fields, including finance, defense, justice, and foreign relations. Additionally, specialized officials like the amatya (finance minister), dandapala (law and order), and samaharta (chief revenue officer) were responsible for executing specific administrative functions. This well-structured bureaucracy ensured that the emperor’s directives were implemented across the empire with precision and consistency.

Law and Order

- Legal Codes and Their Enforcement: The Mauryan Empire developed a sophisticated legal system based on written codes, customs, and royal edicts. The Arthashastra, attributed to Chanakya, provides detailed insights into the legal and administrative principles followed during the Mauryan era. The legal system was designed to maintain social order, protect property, and regulate economic activities. Laws were enforced rigorously, and the state played a direct role in adjudicating disputes, whether civil or criminal.

- Role of Spies and Information Networks: One of the most unique aspects of Mauryan governance was its extensive spy network, which was used to gather intelligence, monitor public sentiment, and detect conspiracies. The spy system, known as caturanga bala, was highly effective and operated under the emperor’s direct control. Spies, often disguised as ordinary citizens, reported on both internal and external affairs, providing the emperor with vital information on governance, crime, and military activities. This intelligence network helped the Mauryan rulers preempt rebellions, maintain law and order, and curb corruption within the administration.

- Criminal Justice System and Punishment: The Mauryan criminal justice system was strict, with a clear focus on deterrence and maintaining social stability. Crimes such as theft, corruption, and treason were met with severe penalties, often including fines, corporal punishment, or even death. The judiciary was overseen by appointed judges, and cases were decided based on evidence, witness testimonies, and legal codes. While the system was punitive, it also incorporated rehabilitative measures for minor offenders, reflecting a balance between justice and social welfare.

Economic Policies

- Taxation and Revenue Collection: The Mauryan Empire’s economic strength was built on a well-regulated taxation system, which was one of the primary sources of state revenue. Land tax, known as bhaga, was the most significant form of taxation, typically amounting to a quarter of the agricultural produce. Additional taxes were levied on trade, industry, and professions. Revenue collection was meticulously organized, with officials at every level ensuring that taxes were collected and remitted to the central treasury. This steady flow of revenue enabled the state to fund its military campaigns, public works, and welfare programs.

- State Control of Trade and Commerce: The Mauryan state exercised considerable control over trade and commerce, both within its territories and in international markets. The empire was strategically located along key trade routes, facilitating commerce with regions as far as the Mediterranean, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia. The state regulated trade by imposing tariffs, ensuring quality control, and maintaining infrastructure such as roads and ports. Royal monopolies were also established on essential goods like minerals, forests, and certain luxury items, generating significant revenue for the state. Markets were overseen by officials who ensured fair pricing and prevented exploitation.

- Agricultural Policies and Land Management: Agriculture was the backbone of the Mauryan economy, and the state took active measures to enhance agricultural productivity. Land management policies included irrigation projects, the construction of dams and canals, and the distribution of uncultivated lands to farmers. The state encouraged the cultivation of diverse crops and the use of advanced farming techniques. Land ownership was carefully documented, and disputes were resolved by local officials, ensuring that agriculture remained stable and profitable. The state also provided support in times of drought or famine, demonstrating a commitment to rural welfare.

Reign of Emperor Ashoka

Emperor Ashoka, often regarded as one of the most remarkable rulers in world history, reigned from around 268 BCE to 232 BCE. His leadership transformed the Mauryan Empire, leaving a lasting legacy on governance, religion, and ethics. His reign is characterized by a dramatic shift from aggressive military conquests to a rule based on compassion, non-violence, and moral responsibility.

Ashoka’s Early Conquests and the Kalinga War

Ashoka’s reign began in a manner similar to his predecessors, focused on expanding the empire’s boundaries through military conquest. After ascending to the throne following a succession struggle, Ashoka continued the Mauryan tradition of aggressive territorial expansion. His early years as emperor saw successful campaigns that extended the empire’s reach further into the Indian subcontinent.

The turning point in Ashoka’s reign was the brutal Kalinga War, fought around 261 BCE. The Kalinga region (modern-day Odisha) was a prosperous and strategically important territory along the eastern coast of India. Despite Kalinga’s strong resistance, Ashoka’s forces emerged victorious, but the war came at a tremendous human cost. Historical records and Ashoka’s own inscriptions describe the extensive loss of life and suffering caused by the conflict. It is estimated that over 100,000 people were killed, and many more were displaced or injured.

Ashoka’s Transformation After the Kalinga War

The aftermath of the Kalinga War marked a profound transformation in Ashoka’s outlook and governance. Witnessing the horrors of war deeply affected him, leading to a moral and spiritual awakening. Ashoka publicly expressed his remorse in his edicts, where he lamented the violence and suffering caused by his ambition. This introspection catalyzed his conversion to Buddhism and a commitment to non-violence (ahimsa).

Ashoka’s transformation was not limited to personal belief; it had far-reaching implications for the empire’s administration. He renounced further conquests and adopted a policy of dhamma-vijaya (victory through righteousness) instead of digvijaya (military conquest). His reign from this point onward was defined by the promotion of ethical governance, compassion, and social welfare, signaling a shift from the traditional imperial focus on expansion to a more humane and spiritually guided rule.

Spreading the Dhamma and Buddhism of Ashoka

Ashoka’s embrace of Buddhism led to the promotion of dhamma, a concept rooted in the principles of morality, justice, and social harmony. Although dhamma drew heavily from Buddhist teachings, Ashoka’s approach was inclusive and non-sectarian, emphasizing universal values like truth, compassion, and tolerance across religious and cultural divides.

To propagate dhamma, Ashoka embarked on a wide-reaching campaign of public education. He spread Buddhist teachings by dispatching missionaries across India and to distant regions, including Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka, and parts of the Hellenistic world. Ashoka’s efforts played a crucial role in transforming Buddhism from a relatively localized religious tradition into a global faith.

The emperor also implemented dhamma within his empire through practical measures. He encouraged ethical conduct among his subjects, promoted social justice, and emphasized non-violence towards both humans and animals. Ashoka’s concept of dhamma was not purely religious; it extended to matters of governance, law, and public welfare, reflecting his belief that a ruler’s duty was to ensure the well-being of all living beings.

Ashoka’s Pillars, Edicts, and Inscriptions

Ashoka’s commitment to spreading dhamma and governing ethically is immortalized in the numerous pillars, edicts, and inscriptions he commissioned across the empire. These inscriptions, written in various languages such as Prakrit, Greek, and Aramaic, were engraved on rocks, pillars, and caves and served as public proclamations of his policies and values.

Among the most notable of these are the Ashoka Pillars, grand stone columns strategically placed throughout the empire. These pillars feature elaborately sculpted capitals, with the Lion Capital at Sarnath being the most renowned and now serving as India’s national emblem. The inscriptions on these pillars address various subjects such as moral teachings, social welfare, religious tolerance, and Ashoka’s ideals of principled governance.

The content of these inscriptions reveals Ashoka’s deep concern for the welfare of his subjects. He instructed his officials to practice and promote dhamma, protect the rights of all communities, and ensure justice. Ashoka’s edicts also emphasize non-violence, environmental conservation, and kindness towards animals, reflecting the broad and progressive nature of his governance. These inscriptions remain invaluable historical sources, providing a window into the moral and political philosophy that guided Ashoka’s reign.

Influence on Governance, Welfare, and Non-Violence

Ashoka’s governance model was a blend of administrative efficiency and ethical principles, setting him apart as one of history’s most humane rulers. He established a system where governance was deeply intertwined with moral responsibility. This was evident in the welfare measures introduced during his reign, including the construction of hospitals, roads, rest houses, and the planting of medicinal herbs. Ashoka’s approach to governance was centered on the idea that the state exists to serve the people, a principle that informed every aspect of his administration.

Ashoka appointed officials known as dhamma-mahamattas, who were responsible for promoting dhamma and overseeing the welfare of the people, particularly the poor, elderly, and marginalized. These officials acted as a bridge between the emperor and his subjects, ensuring that his policies were effectively implemented and that grievances were addressed.

Non-violence became a cornerstone of Ashoka’s governance, influencing his policies on justice and law enforcement. While the legal system remained robust, Ashoka sought to reduce the use of capital punishment and corporal punishment, promoting rehabilitation and moral reformation instead. His support for nonviolent approaches to animal care included the development of veterinary clinics and the outlawing of animal sacrifice.

The impact of Ashoka’s reign was not limited to his time. His promotion of Buddhism and non-violence left a lasting legacy, influencing not only Indian society but also cultures across Asia. Ashoka’s governance model, with its emphasis on welfare, moral responsibility, and ethical leadership, remains a significant reference point in discussions on good governance and the role of ethics in statecraft.

Culture and Society

The Mauryan Empire’s influence extended beyond politics and governance, shaping the cultural and social landscape of ancient India. The period saw a flowering of religious thought, artistic expression, and the development of societal structures that reflected the diversity and complexity of the empire. Under the rule of Ashoka, cultural and social life evolved in ways that laid the foundation for subsequent Indian civilizations.

Religion and Philosophy

Diversity of Religious Practices in the Empire

The Mauryan Empire was home to a diverse range of religious beliefs and practices. Hinduism remained predominant, with the worship of gods like Vishnu, Shiva, and various local deities. However, the period was marked by the rise of heterodox sects, particularly Buddhism and Jainism, which offered alternative spiritual paths focused on non-violence and renunciation. The coexistence of multiple religious traditions was characteristic of the Mauryan era, where religious tolerance was promoted, especially under Ashoka.

Rise of Buddhism and Jainism

The Mauryan era witnessed significant growth in Buddhism and Jainism, both of which challenged the rigid rituals and hierarchies of Vedic Hinduism. Chandragupta Maurya himself was influenced by Jainism in his later years, reportedly retiring to Karnataka where he embraced Jain asceticism. However, it was Ashoka’s patronage of Buddhism that had the most profound impact. After the Kalinga War, Ashoka not only adopted Buddhism but actively propagated it across his empire and beyond. He convened the Third Buddhist Council and sent missionaries to Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, and Hellenistic territories, facilitating the global spread of Buddhism.

Interaction with Hellenistic Thought

The Mauryan Empire was part of a larger Eurasian network of trade and cultural exchange. Following Alexander the Great’s campaigns, the Mauryas maintained contact with the Hellenistic world, leading to interactions between Greek and Indian philosophies. This exchange influenced Indian astronomy, medicine, and art. The incorporation of foreign ideas and the empire’s policy of religious pluralism created an environment where various schools of thought coexisted and influenced each other.

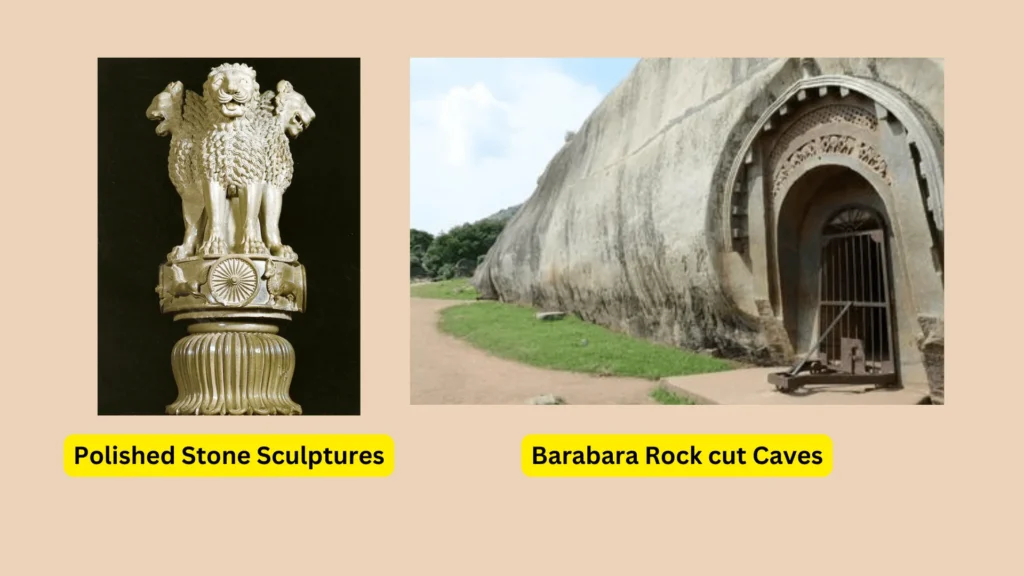

Art and Architecture

The Mauryan period laid the groundwork for some of the most iconic structures and artistic styles in Indian history. The architecture and sculpture of this era reflect both the imperial authority of the Mauryan rulers and their commitment to disseminating moral and religious values.

Iconic Structures

- Pillars and Edicts: Ashoka’s stone pillars are among the most enduring symbols of the Mauryan Empire. These monolithic columns, erected across the empire, were inscribed with edicts in the Brahmi script, promoting dhamma (righteousness). The pillars, made from polished sandstone, often stood between 40 and 50 feet tall and were topped with finely carved animal capitals, the most famous being the Lion Capital at Sarnath, which later became India’s national emblem. The inscriptions on these pillars, written in the vernacular, conveyed messages of moral conduct, social harmony, and non-violence.

- Stupas: The construction of stupas—hemispherical structures containing relics of the Buddha—became central to Buddhist worship during the Mauryan period. The Great Stupa at Sanchi, commissioned by Ashoka, is one of the oldest and most important Buddhist monuments in India. It features a massive stone dome, surrounded by intricately carved gateways (toranas) depicting scenes from the Buddha’s life. The stupa architecture from this period influenced the construction of similar structures across Asia, establishing a tradition that persisted for centuries.

- Polished Stone Sculptures: The Mauryan period is renowned for its polished stone sculptures, which were marked by smooth finishes and detailed craftsmanship. The Lion Capital of Sarnath, sculpted from a single sandstone block, stands as the pinnacle of Mauryan artistry. Depicting four lions standing back-to-back atop a cylindrical base adorned with carvings of a bull, horse, elephant, and lion, the capital symbolizes power, unity, and the spread of dhamma. These sculptures marked the beginning of a distinct Indian artistic tradition that blended realism with symbolic representation.

- Rock-Cut Caves: The Barabar-Nagarjuni hills in Bihar house some of the earliest examples of rock-cut architecture in India, dating back to the Mauryan period. These caves were initially carved as monastic retreats for the Ajivikas, a heterodox sect. The Lomas Rishi Cave, with its semi-circular facade and polished interior, is a notable example. These caves reflect advanced engineering skills and set the precedent for later rock-cut structures like those at Ajanta and Ellora.

Evolution of Mauryan Sculpture and Art Styles

Mauryan art represented a departure from the predominantly wooden architecture of earlier periods. The use of stone, combined with a focus on polished surfaces and intricate carvings, became the hallmark of this era. The sculptural style was influenced by both indigenous traditions and Persian and Hellenistic models, creating a unique fusion that laid the groundwork for subsequent Indian art.

Influence on Subsequent Indian Architecture

The architectural innovations of the Mauryan period, such as the use of stone pillars, stupas, and rock-cut caves, had a lasting impact on Indian architecture. The Mauryan emphasis on symbolism, combined with technical advancements, influenced the development of temple architecture, sculpture, and urban planning in later dynasties like the Guptas and Cholas.

Daily Life and Social Structure

The Mauryan Empire was a complex society with a well-defined social hierarchy, diverse cultural practices, and a dynamic urban life. The empire’s prosperity and stability allowed for the flourishing of various cultural activities, shaping the everyday life of its citizens.

Class Hierarchy and Societal Roles

Mauryan society was structured around the varna system, which classified people into four main groups: Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (traders), and Shudras (laborers). However, the Mauryan Empire was more socially diverse, with the inclusion of communities like the Ajivikas, Buddhists, and Jains. Economic roles were also significant in defining social status, with merchants and artisans playing an essential part in urban centers. The jati (caste) system, while present, was less rigid compared to later periods, allowing for some degree of social mobility.

Role of Women and Families

Women in the Mauryan period played various roles within both domestic and public spheres. While patriarchal norms were prevalent, women had certain rights, including property ownership and participation in religious activities. Royal women, like Ashoka’s queens, wielded influence in political and social matters. The family was the primary social unit, with joint families being the norm. Marriage was considered a social duty, and rituals surrounding birth, marriage, and death were central to Mauryan life.

Festivals, Music, and Culinary Practices

Festivals were integral to Mauryan society, with celebrations linked to religious events, seasonal cycles, and royal occasions. Both Hindu and Buddhist rituals were widely observed, with communal gatherings and temple festivities. Music and dance were important aspects of entertainment and worship. Instruments like the veena, drums, and flutes were commonly played. Mauryan cuisine was diverse, with a diet that included grains, pulses, fruits, and vegetables. The emphasis on vegetarianism grew with the spread of Buddhism and Jainism, although non-vegetarian food was also consumed by many sections of society.

Decline and Fall of the Mauryan Empire

The decline and eventual fall of the Mauryan Empire is a pivotal chapter in Indian history. After the reign of Ashoka, the empire, which had reached its zenith in terms of territorial expansion, administration, and cultural influence, gradually weakened due to a combination of internal and external factors. The collapse of the Mauryan dynasty led to the fragmentation of the subcontinent, paving the way for regional kingdoms to rise in prominence.

The Succession of Weak Rulers After Ashoka

Ashoka’s reign marked the peak of Mauryan power, but his death in 232 BCE left a leadership vacuum that the succeeding rulers struggled to fill. The immediate successors of Ashoka, such as his son Dasaratha and later rulers like Samprati and Shalishuka, lacked both the political acumen and the military prowess required to maintain the vast empire. Their inability to enforce centralized control resulted in the gradual loss of territories and growing discontent among provincial governors and local chieftains.

The weak leadership post-Ashoka also led to the erosion of the central authority. The Mauryan rulers that followed focused more on internal palace politics and court intrigues rather than strengthening the administrative framework or addressing external threats. This period witnessed the empire’s gradual fragmentation, as local governors and regional leaders began asserting their independence, setting the stage for the eventual collapse.

Internal Strife and Administrative Challenges

The centralized nature of the Mauryan administration, which had been its strength during Chandragupta and Ashoka’s reigns, became a source of weakness as the empire expanded. The vast territory required efficient communication, coordination, and control, but the later Mauryan rulers struggled to manage the empire’s administrative machinery. The absence of strong leadership led to internal divisions and power struggles among ministers, regional satraps, and royal family members.

Administrative corruption also took root during this period. The extensive bureaucracy, while essential for governance, became bloated and inefficient. Reports of bribery, nepotism, and mismanagement became increasingly common, leading to the empire’s weakened ability to govern effectively. The elaborate espionage network, which had once been a pillar of the Mauryan administration, became less reliable, allowing for unrest and rebellion to brew undetected.

Furthermore, Ashoka’s embrace of Buddhism and the subsequent promotion of non-violence had significant implications for the empire’s military readiness. While Ashoka’s moral policies and focus on dhamma (righteousness) contributed to internal stability during his reign, they inadvertently led to a decline in military discipline and preparedness. The weakened military structure left the empire vulnerable to external invasions and internal rebellions.

Economic Decline and Loss of Territorial Control

The economic decline of the Mauryan Empire was a crucial factor in its downfall. The empire’s economy, which had once thrived on agriculture, trade, and industry, started to stagnate due to a combination of high taxation, poor administrative efficiency, and declining agricultural productivity. The resources that had previously been used to maintain the large standing army, build infrastructure, and support the bureaucracy were gradually depleted.

The loss of key trade routes and territories, particularly in the western and northwestern regions, further exacerbated the economic situation. These regions were vital for controlling trade with Central Asia and the Hellenistic world. As provincial governors and local rulers asserted independence, they began retaining the revenue generated from these trade routes, depriving the central administration of crucial income. This led to the empire’s reduced capacity to fund military campaigns or maintain infrastructure, hastening the loss of territorial control.

Additionally, the empire’s reliance on a heavy tax burden strained the agrarian economy. The excessive taxation and the pressure on farmers to produce surplus grain for state coffers led to widespread discontent among the peasantry, triggering localized revolts. These economic pressures were compounded by a decline in internal trade, with local economies becoming increasingly isolated as the central authority weakened.

Final Collapse and Emergence of Regional Powers

The final collapse of the Mauryan Empire is often attributed to the reign of Brihadratha, the last Mauryan ruler, who faced mounting challenges from within and outside the empire. In 185 BCE, Brihadratha was assassinated by his own general, Pushyamitra Shunga, marking the end of the Mauryan dynasty and the beginning of the Shunga dynasty. Pushyamitra’s coup symbolized the definitive shift in power from the Mauryas to regional rulers.

The fall of the Mauryan Empire resulted in the emergence of several regional kingdoms and local powers. The Shungas, who established their rule in the Gangetic plains, were followed by the Kanvas in the eastern region, while the Satavahanas rose to prominence in the Deccan. In the northwest, the Indo-Greeks, who had established themselves in Bactria, took advantage of the Mauryan decline to expand their territories into India. This period saw the re-emergence of fragmented political entities, with no single power able to dominate the subcontinent as the Mauryas had done.

The disintegration of the Mauryan Empire also had cultural implications. While the centralized administration and uniform legal codes dissolved, the Mauryan legacy persisted in the form of art, architecture, and the spread of Buddhism. The decentralization led to the diversification of regional cultures, contributing to the rich tapestry of Indian civilization in the following centuries.

Legacy of the Mauryan Empire

The Mauryan Empire left an indelible mark on Indian history, shaping the subcontinent’s political, religious, and cultural landscape in ways that endured for centuries. The Mauryan era, particularly under the reigns of Chandragupta Maurya and Ashoka, set precedents in governance, administration, religion, and art that influenced not only subsequent Indian empires but also civilizations across Asia.

Lasting Impact on Indian Governance and Administration

One of the most significant contributions of the Mauryan Empire was the establishment of a centralized governance model. Chandragupta Maurya, with the guidance of his advisor Chanakya (Kautilya), laid the foundation for a bureaucratic and well-structured administration that managed the empire’s vast and diverse territories. The Arthashastra, attributed to Chanakya, offers a detailed account of governance, statecraft, and economic management, principles that guided the Mauryan administration.

Centralized Government System

The Mauryan Empire was one of the first in India to create a highly organized central government that extended its authority over a large territory. This centralized system was designed to ensure that the emperor’s directives reached even the most distant provinces. The administration was divided into provinces, each governed by a royal prince or trusted official, ensuring efficient management at the local level. This model of governance, with its emphasis on a strong central authority supported by a well-organized bureaucracy, became the blueprint for future Indian empires, including the Gupta Empire.

Political Stability and Uniform Legal Codes

The Mauryan Empire introduced uniform legal codes and standardized laws that applied across its territories. The legal system emphasized justice, social welfare, and the protection of citizens’ rights. The idea of a state guided by dharma (moral law), particularly during Ashoka’s reign, had a profound influence on subsequent rulers, who sought to balance political authority with ethical governance.

Spread of Buddhism Across Asia

One of the most far-reaching legacies of the Mauryan Empire was the promotion and spread of Buddhism, particularly during Ashoka’s reign. After the Kalinga War, Ashoka’s conversion to Buddhism and his subsequent efforts to propagate the religion had a transformative effect on the religious landscape of Asia.

Ashoka’s Missionary Activities

Ashoka is credited with sending Buddhist missionaries beyond the borders of India, reaching as far as Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and the Hellenistic kingdoms. His efforts laid the foundation for Buddhism’s spread across the Indian subcontinent and beyond, eventually becoming one of the major world religions. Monks and scholars, such as Mahinda and Sanghamitta, who were dispatched to Sri Lanka, played a crucial role in establishing Theravada Buddhism, which remains the dominant form of Buddhism in the region today.

The Legacy of Ashoka’s Dhamma

Ashoka’s promotion of dhamma (righteousness), which emphasized compassion, non-violence, and religious tolerance, resonated across Asia. His edicts, inscribed on stone pillars and rocks, conveyed messages of moral conduct and ethical living. These edicts were among the earliest instances of state-sponsored public communication aimed at educating the populace. The principles of Ashoka’s dhamma continue to be revered as an integral part of Buddhist teachings.

Influence on Subsequent Empires, Like the Gupta Empire

The Mauryan Empire’s administrative and political structures served as a foundation for subsequent empires in India, particularly the Gupta Empire, which is often considered the golden age of Indian civilization. The Gupta rulers adopted and refined the Mauryan model of governance, centralization, and administrative efficiency while introducing their own innovations.

Continuity in Bureaucratic Systems

The Mauryan emphasis on a professional bureaucracy, provincial governance, and a detailed revenue system was inherited and adapted by the Gupta Empire. Although the Gupta administration was more decentralized than the Mauryan system, the basic structure of provincial and local governance remained similar. The idea of a stable central authority balanced by regional autonomy became a recurring feature in Indian political history.

Cultural and Intellectual Continuity

The Gupta Empire also drew inspiration from the Mauryan legacy in terms of art, architecture, and intellectual pursuits. The classical art and literature of the Gupta period, often regarded as the pinnacle of Indian cultural achievements, can trace its roots back to the artistic and architectural developments of the Mauryan era. Additionally, the Mauryan tradition of promoting scholarship and religious tolerance found echoes in Gupta policies.

Architectural and Cultural Contributions

The Mauryan Empire made significant contributions to Indian art, architecture, and culture, laying the groundwork for future artistic developments in the subcontinent.

Stone Architecture and Sculptures

The Mauryan period marked the transition from wood to stone architecture, setting a new standard for durability and grandeur. Ashoka’s pillars, with their finely polished surfaces and symbolic capitals, represent some of the earliest examples of monumental stone art in India. The Lion Capital of Sarnath, now India’s national emblem, is an enduring symbol of the Mauryan Empire’s artistic excellence.

Development of Stupas and Rock-Cut Architecture

The construction of stupas, particularly the Great Stupa at Sanchi, became a defining feature of Buddhist architecture, influencing religious structures across Asia. The evolution of stupa design, with its hemispherical dome, circumambulatory paths, and intricate gateways, laid the foundation for Buddhist architectural traditions that persisted for centuries. Similarly, the rock-cut caves at Barabar, with their polished interiors and religious significance, represent early experiments in rock-cut architecture that later inspired the magnificent caves of Ajanta and Ellora.

Cultural Synthesis and Artistic Expression

The Mauryan Empire, particularly during Ashoka’s reign, facilitated a synthesis of indigenous and foreign artistic traditions. The interaction with Hellenistic culture, as seen in the Gandhara region, led to the blending of Greco-Roman elements with Indian motifs, resulting in a unique artistic style that would influence Indian sculpture for generations.

Promotion of Literature and Knowledge

The Mauryan period also witnessed the flourishing of literature, philosophy, and intellectual discourse. The Arthashastra, attributed to Chanakya, remains a seminal work in political theory and economic management. The spread of Buddhism during Ashoka’s reign contributed to the growth of a rich literary tradition, with the Tripitaka and other Buddhist texts being compiled and disseminated.

Conclusion & FAQs

The Mauryan Empire stands as a landmark chapter in Indian history, symbolizing the rise of the first large-scale centralized state on the subcontinent. From its foundation under Chandragupta Maurya to its golden age under Emperor Ashoka, the Mauryan Empire set the stage for significant developments in governance, culture, religion, and diplomacy. Its influence on subsequent Indian empires and its contributions to global history make it one of the most significant periods of ancient India.

The Mauryan Empire unified most of the Indian subcontinent, marking the first time such extensive territories were brought under a single political entity. The establishment of a centralized administration, efficient bureaucracy, and a robust military allowed the empire to flourish and maintain stability across diverse regions. Ashoka’s reign, particularly after the Kalinga War, emphasized the ethical governance model, the promotion of Buddhism, and non-violence, leaving a profound legacy that extended far beyond India.

The empire’s contributions to architecture, art, and literature, alongside the development of key principles in statecraft and economics, set precedents that influenced not only later Indian empires but also other civilizations across Asia. The Mauryan period is remembered not just for its political achievements but for fostering a cultural renaissance that laid the foundations for India’s rich civilizational heritage.

The Mauryan Empire’s administrative structure and political organization served as a blueprint for future empires like the Guptas, who further refined and expanded upon the governance systems established during this era. The use of centralized power balanced with provincial autonomy, a professional bureaucracy, and a codified legal system became recurring themes in Indian political history.

In the religious domain, Ashoka’s efforts to spread Buddhism had a lasting impact on Asia’s spiritual landscape, influencing regions as far as Sri Lanka, China, and Japan. The architectural innovations, particularly in stupa construction and rock-cut architecture, set stylistic trends that endured for centuries.

Moreover, the legacy of Ashoka’s dhamma—a governance model centered on moral and ethical principles—resonates in modern discussions about state responsibility and social welfare. The symbols and ideals promoted during the Mauryan period continue to influence contemporary India, with the Lion Capital of Sarnath serving as the national emblem and Ashoka’s wheel adorning the Indian national flag.

Today, the Mauryan legacy is evident in various aspects of Indian culture and governance. The ethical governance model advocated by Ashoka remains relevant in discussions about leadership, social responsibility, and human rights. The spread of Buddhism, with its emphasis on compassion, non-violence, and spiritual growth, continues to shape the cultural and religious practices of millions across Asia.

In the field of architecture and art, the iconic structures from the Mauryan period, such as the Ashokan pillars, stupas like the Great Stupa at Sanchi, and rock-cut caves at Barabar, remain as testaments to the empire’s grandeur and innovative spirit. These structures are not only historical landmarks but also continue to inspire modern architecture and cultural preservation efforts.

The Mauryan period’s emphasis on statecraft, codified law, and efficient administration laid the groundwork for subsequent developments in governance, which are reflected in India’s current administrative frameworks. The enduring appeal of Chanakya’s Arthashastra, which is still studied as a seminal text on political strategy and economics, underscores the timeless relevance of the Mauryan Empire’s intellectual contributions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What were the key accomplishments of the Mauryan Empire?

The Mauryan Empire achieved political unification of most of the Indian subcontinent, established a centralized and efficient administration, and promoted a governance model rooted in ethical principles under Ashoka. Significant achievements include the spread of Buddhism, construction of iconic monuments like the Ashokan pillars and stupas, and advancements in statecraft as documented in the Arthashastra.

How did Ashoka the Great influence the spread of Buddhism?

Ashoka played a pivotal role in promoting Buddhism after his conversion following the Kalinga War. He sent missionaries across Asia, including to Sri Lanka, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia, where they helped establish Buddhist communities. Ashoka’s inscriptions, which emphasized moral and spiritual teachings, were also instrumental in spreading Buddhist principles.

What were the primary factors that led to the fall of the Mauryan Empire?

The fall of the Mauryan Empire was primarily due to weak leadership after Ashoka, internal strife, administrative inefficiency, economic decline, and the loss of territorial control. Succession disputes and decentralization led to the erosion of central authority, while increasing corruption and high taxation fueled discontent among the populace. The assassination of the last Mauryan ruler, Brihadratha, by his general Pushyamitra Shunga marked the final collapse of the empire.

How did the Mauryan administration differ from earlier Indian states?

The Mauryan administration was more centralized and organized than earlier Indian states. It featured a hierarchical bureaucracy, a professional spy network, a well-defined legal system, and a structured tax collection process. The empire was divided into provinces, each governed by royal princes or trusted officials, allowing for efficient management across vast territories. The detailed governance principles laid out in the Arthashastra highlight the sophistication of Mauryan statecraft.

What is the significance of the Mauryan Empire in world history?

The Mauryan Empire’s significance in world history lies in its pioneering governance model, its role in spreading Buddhism globally, and its contributions to art, architecture, and statecraft. Ashoka’s promotion of non-violence and ethical governance had a lasting influence on world philosophies and religious thought. The empire also served as a bridge for cultural exchange between India and the Hellenistic world, contributing to the development of cross-cultural connections in ancient times.