Introduction

Brief Overview of Monkeypox

Monkeypox is a viral disease transmitted from animals to humans, caused by the Monkeypox virus, which belongs to the Orthopoxvirus family. The disease primarily affects animals but can also spread to humans. While the symptoms resemble those of smallpox, Monkeypox is typically less severe. The condition is characterized by fever, swollen lymph nodes, and a distinctive rash that progresses through various stages, from flat lesions to scabs. Despite its name, the virus is not exclusive to monkeys and is commonly found in rodents. Human infections, although rare, can lead to significant health concerns, especially in regions with limited healthcare resources.

Background and Relevance: Why It’s a Concern Today

In recent years, Monkeypox has garnered global attention due to its increasing spread beyond its traditional endemic regions in Central and West Africa. The 2022 global outbreak highlighted how the disease could rapidly affect countries with no history of Monkeypox, raising alarms about its potential to become a widespread health issue. Factors like global travel, close-contact transmission, and shifting ecological conditions have contributed to its spread. The outbreak underscored the importance of surveillance, public health preparedness, and vaccination strategies to contain future outbreaks. As a result, understanding Monkeypox has become crucial for both the public and healthcare systems worldwide.

Historical Context and Origins of the Virus

The first recorded case of Monkeypox in humans was documented in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo, in a child suspected to have smallpox. The virus, however, was first identified in 1958 during an outbreak among laboratory monkeys, leading to its misleading name. Since then, sporadic outbreaks have occurred primarily in rural, forested regions of Africa, where people are more likely to come into contact with infected animals.

Over time, the virus spread across countries and continents, with significant outbreaks reported in the 2000s. Its resurgence in recent years is attributed to declining immunity against orthopoxviruses after the cessation of smallpox vaccination, which also offered cross-protection against Monkeypox. The virus’s ability to jump from animals to humans, coupled with human-to-human transmission, has kept it a persistent threat in both endemic and non-endemic regions.

What is Monkeypox?

Definition and Classification as a Zoonotic Viral Disease

Monkeypox is a zoonotic viral disease, meaning it can be transmitted from animals to humans. The disease is caused by the Monkeypox virus, which belongs to the Orthopoxvirus genus, the same family of viruses that includes the now-eradicated smallpox virus. This classification is significant because zoonotic diseases often involve complex transmission dynamics, where the virus can move between animal reservoirs and human hosts.

Monkeypox primarily infects wild animals, such as rodents and primates, and human infections are typically linked to direct contact with these animals or their bodily fluids. In humans, the virus causes a disease characterized by symptoms that include fever, headache, muscle aches, and a rash that eventually forms pustules and scabs. While Monkeypox is less deadly than smallpox, it still poses a serious public health threat, particularly in regions where the virus is endemic, and healthcare resources are limited.

Brief History and Discovery of Monkeypox

Monkeypox was first identified in 1958 during an outbreak among laboratory monkeys used for research in Denmark, hence the name “Monkeypox.” However, it wasn’t until 1970 that the first human case was reported in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This case occurred in a 9-month-old boy who was initially suspected to have smallpox, underscoring the clinical similarities between the two diseases. Since its discovery, Monkeypox has been primarily confined to Central and West Africa, where sporadic outbreaks have occurred, often in remote areas.

The disease remained relatively obscure until a series of larger outbreaks in the early 21st century, which included cases outside of Africa, raising global awareness of its potential as an emerging infectious disease. In 2003, the first outbreak outside of Africa occurred in the United States, linked to imported animals from Ghana, which further highlighted the zoonotic nature of the virus.

Differences Between Monkeypox and Similar Diseases

Although Monkeypox and smallpox share several similarities, they are distinct diseases with important differences. Both are caused by Orthopoxviruses, leading to similar symptoms such as fever, rash, and pustules. However, there are key differences:

- Severity: Smallpox was a far more severe disease with a higher mortality rate, often around 30%. In contrast, Monkeypox typically has a lower fatality rate, usually between 1% and 10% in severe cases, depending on the strain and healthcare access.

- Transmission: Smallpox was highly contagious and could spread rapidly between humans, primarily through respiratory droplets. While Monkeypox can also spread through respiratory droplets, it requires more prolonged face-to-face contact and is less contagious than smallpox. The zoonotic nature of Monkeypox also means that animal-to-human transmission is a significant route of infection, which was not a factor in smallpox.

- Lymphadenopathy: One distinguishing feature of Monkeypox is the presence of swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy), which typically does not occur in smallpox. This symptom can be a critical diagnostic clue in differentiating the two diseases.

- Global Impact and Eradication: Smallpox was eradicated globally by 1980 through a coordinated vaccination campaign led by the World Health Organization (WHO). Monkeypox, however, continues to cause outbreaks, particularly in parts of Africa, and has the potential for global spread, as evidenced by the 2022 outbreak. The decline in smallpox vaccination has also contributed to the resurgence of Monkeypox, as the smallpox vaccine provided some cross-protection against Monkeypox.

Understanding these differences is crucial for accurate diagnosis, effective public health response, and developing targeted strategies for prevention and treatment.

Causes and Transmission

How Monkeypox Spreads ?

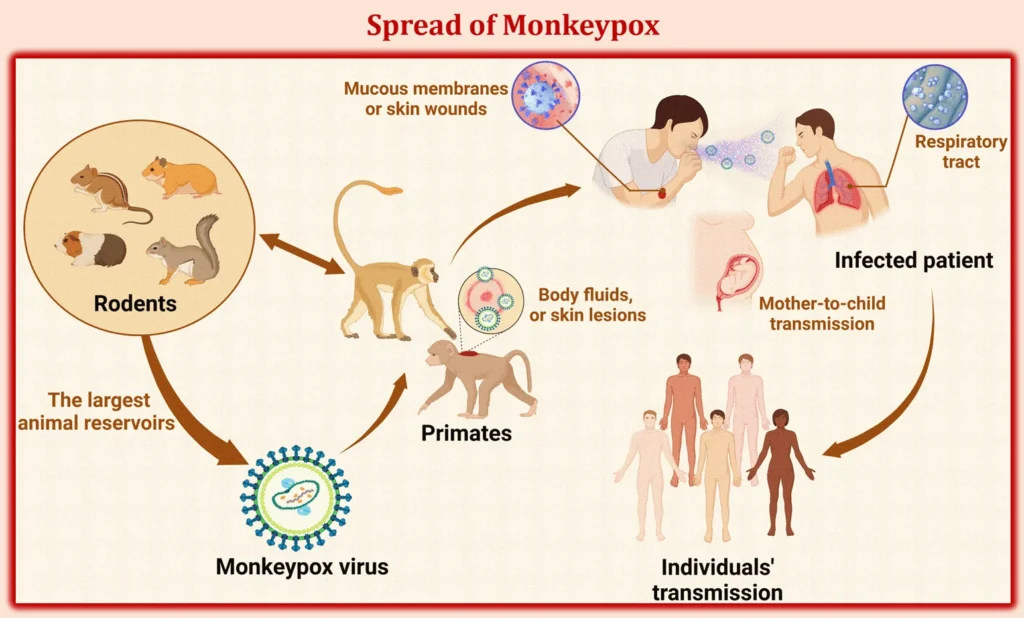

Monkeypox spreads primarily through close contact with an infected person or animal, as well as through contaminated objects and surfaces. The main routes of transmission include:

- Direct Contact: The most common mode of transmission is through direct contact with the skin lesions, bodily fluids, or scabs of an infected individual. The virus can enter the body through broken skin (even if not visibly broken), the respiratory tract, or mucous membranes (eyes, nose, or mouth).

- Respiratory Droplets: Monkeypox can also be transmitted via respiratory droplets from an infected person. However, this typically requires prolonged face-to-face contact, making it less contagious than diseases like COVID-19 or influenza. Close interactions, such as living in the same household or engaging in intimate contact, increase the risk of transmission through this route.

- Contaminated Objects: The virus can survive on surfaces, clothing, and other materials that have come into contact with an infected person’s lesions or bodily fluids. Handling these contaminated items can lead to infection if the virus is transferred to the skin, eyes, or mouth.

Understanding these transmission routes is essential for controlling the spread of Monkeypox, particularly in community and healthcare settings. Preventive measures like isolating infected individuals, practicing good hygiene, and disinfecting contaminated surfaces are key to reducing transmission risks.

Transmission from Animals to Humans

Monkeypox is primarily a zoonotic disease, meaning it originates from animals and can be transmitted to humans. The main reservoirs for the virus are believed to be rodents, including Gambian pouched rats, squirrels, and dormice, although primates can also be carriers. Zoonotic transmission occurs through:

- Animal Bites or Scratches: Direct contact with an infected animal’s blood, bodily fluids, or lesions can transmit the virus to humans. This can happen through bites, scratches, or handling the meat of infected animals.

- Consumption of Infected Meat: In certain regions, hunting and consuming bushmeat (wild animals) is a common practice, which increases the risk of infection. Improperly cooked meat from infected animals can be a source of the virus.

- Indirect Contact: Handling contaminated bedding, cages, or other materials used by infected animals can also lead to transmission.

Once the virus infects a human, it can spread through human-to-human transmission via the methods mentioned above (direct contact, respiratory droplets, and contaminated objects). Human-to-human transmission, though less efficient than zoonotic transmission, has played a significant role in the larger outbreaks seen in non-endemic regions.

High-Risk Groups and Regions Prone to Outbreaks

Certain groups and regions are more susceptible to Monkeypox outbreaks:

- High-Risk Groups

- Healthcare Workers: Those caring for infected patients are at a higher risk, particularly if appropriate protective measures are not in place.

- Household Members: Close contacts of infected individuals, including family members or roommates, are vulnerable to contracting the virus.

- People Engaged in Close Physical Contact: Individuals involved in intimate contact, including sexual activity, are at an elevated risk. Some recent outbreaks have reported cases linked to sexual networks, although Monkeypox is not classified as a sexually transmitted infection.

- Immunocompromised Individuals: Those with weakened immune systems may experience more severe symptoms and complications if infected.

- Regions Prone to Outbreaks:

- Endemic Regions: Central and West Africa, particularly in countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria, are hotspots for Monkeypox due to the presence of natural animal reservoirs and frequent human-animal interactions.

- Non-Endemic Regions Experiencing Outbreaks: The 2022 global outbreak brought Monkeypox into countries outside Africa, highlighting its potential to spread in regions with no prior history of the disease. Urban centers and areas with high population density are particularly at risk due to the ease of person-to-person transmission.

The convergence of factors such as increased global travel, changes in animal habitats, and reduced immunity due to the cessation of smallpox vaccination has contributed to the spread of Monkeypox beyond traditional endemic zones.

Symptoms and Stages of Monkeypox

Incubation Period (6-13 Days Typically)

The incubation period for Monkeypox, the time between exposure to the virus and the onset of symptoms, typically ranges from 6 to 13 days. However, in some cases, it can be as short as 5 days or extend up to 21 days. During this phase, the virus is actively replicating in the body, but the infected individual shows no visible signs of illness. Understanding the incubation period is crucial for monitoring contacts and implementing effective isolation measures to prevent the spread of the disease.

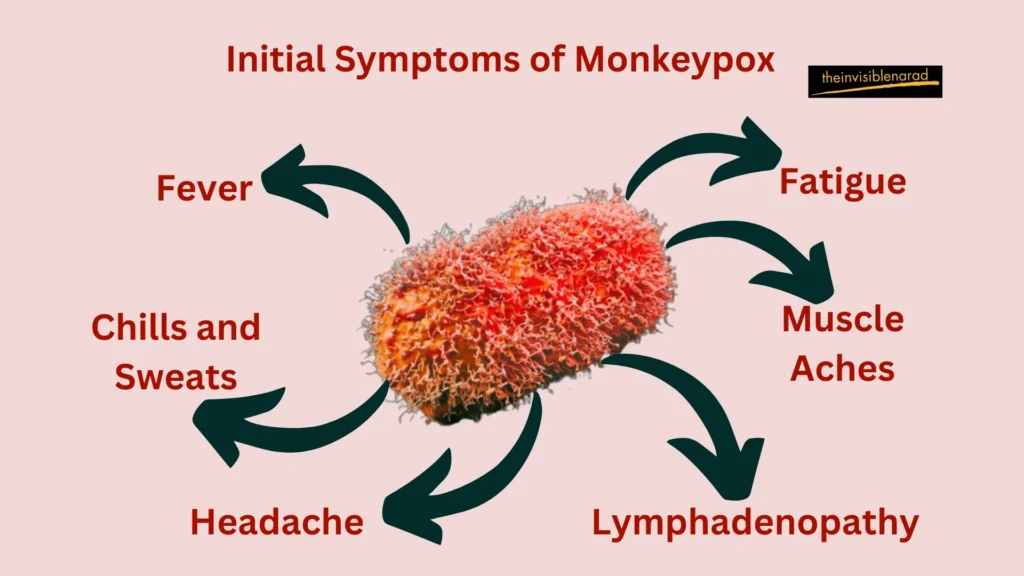

Initial Symptoms: Fever, Headache, Muscle Aches, and Fatigue

Monkeypox initially presents with non-specific flu-like symptoms, making early diagnosis challenging. The first symptoms typically include:

- Fever: A sudden onset of high fever is usually the earliest sign.

- Headache: Intense headaches frequently occur alongside fever.

- Muscle Aches (Myalgia): Generalized body aches and muscle pain are common.

- Fatigue: Individuals may experience profound exhaustion and a significant drop in energy levels.

- Chills and Sweats: Shivering and excessive sweating may occur during this stage.

- Swollen Lymph Nodes (Lymphadenopathy): Unlike smallpox, Monkeypox often involves noticeable swelling of lymph nodes, especially in the neck, armpits, and groin. This is a key distinguishing symptom.

These symptoms typically last 1 to 5 days before the characteristic rash appears, marking the transition to the next stage of the illness.

Rash Development and Progression

The rash associated with Monkeypox is one of its most defining features. It progresses through several stages over a period of 2 to 4 weeks:

- Macules: The rash initially appears as flat, red spots (macules) on the skin. These usually start on the face before spreading to other parts of the body, including the palms, soles, and mucous membranes.

- Papules: Within a few days, the macules elevate to form raised, firm bumps (papules).

- Vesicles: The papules then evolve into fluid-filled blisters (vesicles), resembling chickenpox or herpes lesions.

- Pustules: Over time, the vesicles become pustules—larger, pus-filled lesions that are typically painful to the touch. These pustules are deep-seated and well-circumscribed, often resembling boils.

- Scabs: Finally, the pustules begin to dry out, forming scabs that eventually fall off. This process can leave scars or hyperpigmented areas, depending on the severity and extent of the rash.

The rash usually spreads in a centrifugal pattern, being most concentrated on the face and extremities, while relatively sparing the trunk. In some cases, lesions may also appear inside the mouth, on the genitals, and around the eyes, leading to complications.

Severity of Symptoms and Complications in Certain Cases

While most cases of Monkeypox are self-limiting and resolve within 2 to 4 weeks, the severity of symptoms can vary widely depending on factors like age, underlying health conditions, and the strain of the virus. The West African strain, which has been implicated in recent outbreaks, typically causes milder disease, while the Central African (Congo Basin) strain is associated with higher mortality rates.

Potential Complications

- Secondary Infections: Bacterial infections of the skin lesions can occur, potentially leading to abscesses, sepsis, or cellulitis.

- Respiratory Distress: If the virus spreads to the lungs, it can cause breathing difficulties and pneumonia.

- Encephalitis: In rare cases, the virus can cause inflammation of the brain, leading to neurological complications.

- Ocular Involvement: Lesions around or inside the eyes can result in vision loss if not managed appropriately.

Certain groups are at higher risk for severe outcomes, including young children, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals. In regions with limited healthcare access, complications can be more severe due to delayed diagnosis and inadequate treatment options.

Diagnosis and Detection

How Monkeypox is Diagnosed ?

Diagnosing Monkeypox involves clinical evaluation combined with laboratory testing, as the symptoms can overlap with other viral infections and skin conditions. The primary methods for diagnosing Monkeypox are:

- Clinical Examination: Healthcare providers begin with a thorough examination of the patient’s symptoms, focusing on the characteristic rash and accompanying signs like swollen lymph nodes. However, because the symptoms can be similar to other diseases (such as chickenpox, smallpox, or even some skin infections), lab testing is essential to confirm the diagnosis.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Testing: PCR is the gold standard for diagnosing Monkeypox. It involves detecting the genetic material (DNA) of the Monkeypox virus from samples collected from skin lesions (such as fluid from vesicles or pustules, or crusts from scabs). PCR tests are highly specific and sensitive, making them crucial for accurate identification of the virus.

- Sample Collection: The reliability of the diagnosis depends heavily on the quality and type of samples collected. Swabs from lesions, especially in the early stages, are preferred. In some cases, blood, respiratory samples, and throat swabs may also be tested, although skin lesion samples provide the most definitive results.

Accurate lab diagnosis is critical not only for patient management but also for public health authorities to monitor and control the spread of the virus, especially in non-endemic regions.

Importance of Early Detection for Controlling Outbreaks

Early detection plays a vital role in controlling Monkeypox outbreaks. Identifying cases at an early stage enables timely isolation, treatment, and contact tracing, which are essential measures to prevent further transmission. The importance of early detection includes:

- Preventing Further Spread: Rapid identification and isolation of infected individuals are key to limiting the spread of the virus, particularly in high-density or vulnerable populations.

- Effective Treatment and Care: Early diagnosis allows healthcare providers to manage symptoms more effectively, preventing complications and improving outcomes, especially in severe cases.

- Public Health Interventions: Early detection triggers public health responses such as vaccination campaigns, public awareness initiatives, and enhanced surveillance in affected areas. These actions can help contain localized outbreaks before they escalate into larger public health emergencies.

In recent global outbreaks, delayed diagnosis has often led to wider community spread, underscoring the need for vigilant monitoring and prompt action.

Differential Diagnosis from Other Poxviruses

Differentiating Monkeypox from other poxviruses and similar skin conditions is challenging due to overlapping symptoms. Accurate diagnosis requires careful consideration of various factors, including patient history, clinical presentation, and lab results. Key comparisons include:

- Smallpox: Monkeypox and smallpox have similar clinical features, including fever and a pustular rash. However, Monkeypox typically involves swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy), which are not common in smallpox. Smallpox was also more severe, with a higher fatality rate. Since smallpox was eradicated in 1980, any suspected poxvirus infection today is more likely to be Monkeypox.

- Chickenpox (Varicella-Zoster Virus): Chickenpox also presents with a vesicular rash, but the distribution and progression differ. Chickenpox lesions tend to appear in successive crops, while Monkeypox lesions are more synchronous, with all lesions progressing through the same stages simultaneously. Additionally, chickenpox lesions are typically concentrated on the trunk, while Monkeypox lesions are more likely to appear on the face, palms, and soles.

- Molluscum Contagiosum: This skin condition, caused by another poxvirus, features small, raised bumps with a dimpled center. Unlike Monkeypox, molluscum lesions are painless, and there is no associated fever or systemic illness.

- Syphilis and Other STIs: Some sexually transmitted infections (STIs) can cause rashes or lesions that mimic Monkeypox, particularly in the genital area. Syphilis, for instance, can cause sores and a secondary rash. A thorough history and specific serological tests are necessary to distinguish between these conditions.

- Other Viral Exanthems and Skin Infections: Conditions like herpes simplex, impetigo, and allergic reactions can sometimes be mistaken for Monkeypox. Differentiating them requires detailed clinical assessment, lab tests, and awareness of any exposure history, particularly in areas experiencing Monkeypox outbreaks.

Accurate differential diagnosis ensures appropriate management, reduces the risk of misdiagnosis, and helps in deploying the correct public health responses.

Prevention and Vaccination

Current Vaccines Available

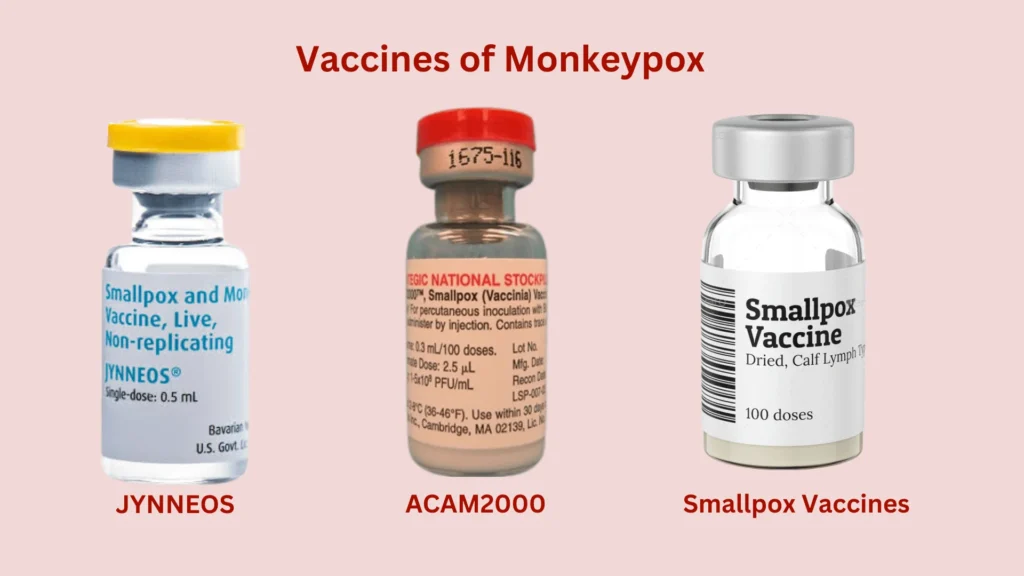

Given the close relation between the Monkeypox virus and the smallpox virus, existing smallpox vaccines have proven effective in preventing Monkeypox. The vaccines currently available include:

- JYNNEOS (Imvamune/Imvanex): This vaccine, developed specifically to target both smallpox and Monkeypox, is a non-replicating, modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) vaccine. JYNNEOS has been approved by the FDA and other global regulatory bodies for use against Monkeypox. Clinical studies indicate that it offers up to 85% protection against the virus. It’s typically administered in two doses, 28 days apart.

- ACAM2000: This is an older smallpox vaccine that can also be used to protect against Monkeypox. Unlike JYNNEOS, ACAM2000 contains a live, replicating virus and is administered using a bifurcated needle. While effective, it carries a higher risk of side effects and is generally reserved for specific groups, such as military personnel or those at high risk.

- Smallpox Vaccines and Cross-Protection: Historically, routine smallpox vaccination provided significant protection against Monkeypox, with immunity lasting for several years. However, since the cessation of widespread smallpox vaccination programs following eradication in 1980, population immunity has declined, contributing to the resurgence of Monkeypox outbreaks in certain regions.

The availability and strategic deployment of these vaccines are vital for curbing Monkeypox transmission, especially in areas experiencing outbreaks.

Preventive Measures

Beyond vaccination, several preventive strategies are critical for minimizing the risk of Monkeypox infection:

- Avoiding Contact with Infected Animals and People: Since Monkeypox is a zoonotic disease, avoiding contact with wild animals (especially rodents and primates) in endemic regions is essential. Similarly, people should avoid close contact with individuals showing symptoms of Monkeypox, such as rashes or lesions. Isolating infected individuals and limiting exposure can prevent the spread within households and communities.

- Practicing Hygiene: Proper hand hygiene, including frequent handwashing with soap and water or using alcohol-based hand sanitizers, reduces the risk of transmission. Wearing masks and protective clothing in high-risk settings, such as healthcare facilities, is also important.

- Safe Handling of Potentially Contaminated Materials: Monkeypox can spread through contact with contaminated objects, such as bedding, clothing, and surfaces. Regular cleaning and disinfection of such items, especially in healthcare settings or households with an infected person, are crucial. Handling pets or animals that may have been exposed should be done with caution.

By adhering to these preventive measures, individuals and communities can significantly reduce their risk of infection, even in the absence of widespread vaccination.

Global Vaccination Efforts and Strategies

The 2022 Monkeypox outbreak highlighted the importance of coordinated global vaccination strategies to control the spread. Key initiatives include:

- Targeted Vaccination in High-Risk Groups: Vaccination campaigns focus on people at higher risk, including healthcare workers, laboratory personnel, and those in close contact with confirmed cases. Some countries have also prioritized vaccination for specific social networks experiencing higher rates of transmission, such as men who have sex with men (MSM).

- Ring Vaccination Strategy: This approach involves vaccinating people who have been exposed to confirmed cases, as well as their close contacts. By creating a “ring” of immune individuals around the infected person, the spread of the virus is contained.

- International Collaboration and Resource Sharing: Organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have coordinated efforts to distribute vaccines, share information, and provide technical support to countries experiencing outbreaks. Ensuring equitable access to vaccines, particularly in resource-limited regions, is a major priority.

- Stockpiling and Strategic Deployment: Given the unpredictability of outbreaks, countries have been building stockpiles of Monkeypox vaccines as a preparedness measure. Strategic deployment based on outbreak severity and population risk assessments ensures that resources are directed where they are needed most.

These global strategies are designed to be adaptive, addressing not only current outbreaks but also preparing for potential future occurrences. The integration of vaccination with public health measures such as surveillance, contact tracing, and public education forms the backbone of a comprehensive response to Monkeypox.

Treatment Options

Symptomatic Treatment and Supportive Care

In most cases, Monkeypox is a self-limiting disease, meaning it typically resolves on its own without the need for extensive medical intervention. However, symptomatic treatment and supportive care play a crucial role in managing the disease and ensuring patient comfort. Key approaches include:

- Pain and Fever Management: Over-the-counter medications such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen are often used to alleviate fever, headaches, and muscle pain. Proper hydration and rest are also essential components of care.

- Skin Lesion Care: Managing the rash is central to treatment. Keeping the skin clean and dry, and applying topical antiseptics, can help prevent secondary bacterial infections. In severe cases, topical or systemic antibiotics may be required if there’s evidence of skin infection.

- Supportive Care for Complications: For patients experiencing complications like respiratory distress, dehydration, or sepsis, more intensive medical care may be necessary. This can include oxygen therapy, intravenous fluids, and in some cases, hospitalization.

The primary goal of symptomatic treatment is to ease the discomfort caused by the disease while monitoring for any signs of complications that may require more specific interventions.

Antiviral Medications and Others Under Study

As of now, no specific treatment is universally approved for Monkeypox, but antiviral medications have shown promise. Among them, Tecovirimat (Tpoxx) stands out:

Tecovirimat (Tpoxx)

Tecovirimat is an antiviral drug initially developed to treat smallpox. It works by inhibiting the viral protein VP37, which is essential for the virus’s ability to spread within the body. In 2018, it was approved by the FDA for the treatment of smallpox, and in recent years, it has been used off-label for Monkeypox under emergency use protocols. Clinical data suggests that Tecovirimat can reduce the severity and duration of symptoms, especially in severe cases or immunocompromised individuals.

Cidofovir and Brincidofovir

These are other antiviral agents with potential efficacy against Monkeypox. Both drugs have shown activity against orthopoxviruses in lab studies, although their use is currently limited due to toxicity concerns and the need for more comprehensive clinical trials.

Ongoing Research

New antiviral agents and treatments are continuously being researched, especially in light of the 2022 global outbreaks. Studies are exploring combinations of antivirals, as well as immune therapies that could offer better outcomes for high-risk patients.

While antivirals offer targeted treatment, they are typically reserved for severe cases, vulnerable populations, or during outbreaks with high transmission rates.

Role of Public Health Initiatives in Managing Outbreaks

Public health initiatives are critical in managing and controlling Monkeypox outbreaks. These strategies combine treatment protocols with preventive and containment measures to limit the spread of the virus. Key aspects include:

- Surveillance and Rapid Response: Early identification of cases through surveillance programs enables quick containment. This includes contact tracing, isolating confirmed cases, and monitoring those at risk. Public health bodies like the WHO and CDC play central roles in coordinating these efforts globally.

- Public Awareness Campaigns: Educating the public about the symptoms, transmission modes, and prevention strategies is vital, especially in regions prone to outbreaks. Clear communication helps dispel misinformation and ensures communities are prepared to act swiftly in case of exposure.

- Access to Vaccines and Treatment: Equitable distribution of vaccines and access to antiviral treatments are core components of public health strategies. Governments and international organizations are working together to ensure that high-risk populations, such as healthcare workers and communities in endemic areas, receive priority access.

- Resource Allocation and Healthcare Support: During outbreaks, public health systems must be equipped to handle increased caseloads. This includes ensuring sufficient medical supplies, trained personnel, and accessible healthcare facilities, especially in rural or under-resourced areas.

The integration of these public health initiatives with clinical care ensures a comprehensive approach to managing Monkeypox, reducing its impact on both individual patients and wider communities.

Monkeypox Outbreaks and Public Health Response

Notable Outbreaks and Their Impact

Monkeypox has had a history of sporadic outbreaks, primarily in Central and West Africa. However, recent years have seen a shift in the virus’s behavior, leading to more widespread and severe outbreaks.

2022 Global Outbreak

The 2022 Monkeypox outbreak was unprecedented in its global reach. What started as isolated cases soon spread across multiple continents, affecting over 100 countries, with thousands of confirmed cases. The outbreak primarily involved Clade II of the Monkeypox virus, which is less severe than Clade I but still poses significant public health risks. The outbreak raised global concern due to the unexpected spread beyond endemic regions, prompting rapid mobilization of vaccines and public health interventions.

2023-2024 Outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

Since January 2023, the DRC has reported over 22,000 suspected cases and more than 1,200 deaths, primarily involving Clade I, which is more virulent than Clade II. This outbreak is more widespread than previous ones in the DRC, with cases extending to neighboring countries such as Burundi, the Central African Republic, and Uganda. The situation is concerning because of the significant mortality rate, especially in children under 15, and the novel modes of transmission, including sexual contact, seen for the first time with Clade I.

The outbreak prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare it a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on August 14, 2024, reflecting the severity of the situation and the need for global cooperation to prevent further spread.

WHO and CDC Guidelines and Response Strategies

Both the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have issued comprehensive guidelines and response strategies to address Monkeypox outbreaks, emphasizing containment, prevention, and treatment.

- WHO Guidelines: The WHO’s response focuses on early detection, vaccination, and public awareness. The declaration of a PHEIC in 2024 was a critical move to draw international attention and resources to the DRC outbreak. The WHO’s recommendations include:

- Surveillance and Rapid Case Identification: Strengthening monitoring systems to quickly identify and isolate cases, especially in regions with high transmission rates.

- Vaccination Campaigns: Deployment of vaccines like JYNNEOS and ACAM2000 in high-risk populations.

- Public Awareness and Education: Targeted campaigns to educate communities about transmission routes, prevention methods, and symptoms.

- CDC Guidelines: The CDC has been actively involved in supporting the response to Monkeypox, both domestically and internationally. In the context of the 2024 outbreak, the CDC emphasizes:

- Risk Assessment and Communication: Advising travelers, healthcare providers, and the public on the risks associated with Clade I Monkeypox, particularly in regions near the DRC.

- Infection Control in Healthcare Settings: Reinforcing the importance of using personal protective equipment (PPE) and proper hygiene in healthcare environments to limit nosocomial transmission.

- Differentiating Risk in the United States: While the risk of Clade I spread to the U.S. remains low due to limited travel connections, the CDC continues to monitor the situation closely and updates its guidance as needed.

Global Efforts to Contain the Spread and Raise Awareness

International collaboration has been pivotal in responding to recent Monkeypox outbreaks. Key global efforts include:

- Coordinated Vaccination Campaigns: In response to the 2024 DRC outbreak, global health agencies have worked together to distribute vaccines to affected areas. The focus has been on vaccinating healthcare workers, people in close contact with confirmed cases, and high-risk populations. These efforts aim to break transmission chains and provide immunity where it’s needed most.

- Strengthening Healthcare Infrastructure in Endemic Regions: Organizations like the CDC and WHO have been providing technical support to improve disease surveillance, laboratory testing, and healthcare delivery in regions like the DRC. This includes ensuring adequate supplies of PPE, antiviral treatments, and other medical resources.

- Raising Public Awareness: Awareness campaigns have been crucial in educating people about how Monkeypox spreads and how to protect themselves. These initiatives target both endemic regions and countries experiencing new outbreaks. Messaging focuses on avoiding contact with sick individuals, safe handling of animals, and understanding the importance of vaccination.

- Research and Data Sharing: Ongoing research into Monkeypox, particularly regarding the efficacy of antivirals like Tecovirimat and the behavior of different Clades, is vital. International partnerships ensure that data is shared promptly, helping inform strategies for controlling the spread and improving treatment protocols.

- Cross-Border Collaboration: Neighboring countries in Central and Eastern Africa, such as Uganda and Rwanda, are working closely with global health bodies to coordinate responses, track cases, and manage cross-border transmission. These collaborative efforts are essential given the interconnected nature of the region’s outbreaks.

The collective global response underscores the importance of vigilance and preparedness in managing emerging infectious diseases like Monkeypox. By integrating vaccination, public education, and robust healthcare strategies, the international community is better equipped to mitigate the impacts of future outbreaks.

The Future of Monkeypox: Challenges and Considerations

Potential for Future Outbreaks

The future of Monkeypox presents both opportunities and challenges for global health. As the virus continues to evolve and spread, understanding its potential for future outbreaks is critical for preparedness and response. Several factors contribute to the likelihood of future outbreaks:

- Global Travel and Trade: Increased international travel and trade can facilitate the spread of Monkeypox beyond endemic regions. The virus’s ability to move between countries and continents poses a risk of introducing outbreaks into new areas, as seen with the 2022 global outbreak.

- Environmental and Ecological Changes: Deforestation, urbanization, and climate change can alter the habitats of wildlife reservoirs of Monkeypox, potentially increasing human-animal interactions. This can lead to higher chances of zoonotic spillover events where the virus jumps from animals to humans.

- Emerging Variants: As with many viruses, Monkeypox has the potential to evolve and produce new variants. Changes in the virus’s genetic makeup could affect its transmission dynamics, severity, and response to existing vaccines and treatments. Monitoring and studying these variants will be crucial in predicting and managing future outbreaks.

- Global Health Disparities: Regions with weaker health infrastructure and limited access to vaccines and treatments are at greater risk. Ensuring equitable distribution of resources and strengthening health systems in these areas are essential for controlling future outbreaks.

Need for Ongoing Surveillance and Research

Continued vigilance and research are vital in managing the Monkeypox threat and preparing for potential future outbreaks. Key areas for ongoing effort include:

- Enhanced Surveillance Systems: Developing robust surveillance systems is crucial for early detection and rapid response. This includes improving case reporting mechanisms, expanding diagnostic capabilities, and strengthening monitoring in both endemic and non-endemic regions.

- Vaccine Development and Evaluation: Ongoing research into the effectiveness and safety of existing vaccines, such as JYNNEOS and ACAM2000, is essential. Additionally, exploring new vaccine candidates and improving existing formulations can help ensure that vaccines remain effective against evolving strains of Monkeypox.

- Antiviral Research: Expanding research into antiviral treatments and other therapeutic options is critical. Current treatments, such as Tecovirimat, are effective but may need to be optimized or supplemented with new drugs to address future challenges.

- Understanding Transmission Dynamics: Continued research into how Monkeypox spreads, including the role of different animal reservoirs and human-to-human transmission routes, will help refine prevention strategies and public health guidelines.

- Global Coordination: Collaborative research efforts across countries and organizations can enhance knowledge sharing and resource allocation. This includes participating in international studies and data collection to build a comprehensive understanding of the virus.

Role of Community Engagement in Prevention and Control

Community engagement is a cornerstone of effective Monkeypox prevention and control. Empowering communities to take proactive measures and participate in health initiatives can significantly impact outbreak management. Key strategies include:

- Public Education Campaigns: Educating communities about Monkeypox, including its symptoms, transmission, and prevention, helps individuals make informed decisions. Effective campaigns should be culturally sensitive, use clear language, and leverage various media platforms to reach diverse audiences.

- Community-Based Surveillance: Involving local communities in surveillance efforts can improve detection and response. Training community health workers and local leaders to identify symptoms and report cases can enhance early detection and intervention.

- Promoting Vaccine Uptake: Engaging communities in vaccination campaigns helps ensure high coverage rates. Addressing vaccine hesitancy through transparent communication and providing access to vaccines in underserved areas are critical components.

- Supporting Local Health Systems: Strengthening local health infrastructure and providing resources for community health programs can improve response capabilities. This includes equipping healthcare facilities, training personnel, and ensuring that communities have access to necessary medical supplies.

- Encouraging Safe Practices: Promoting behaviors that reduce the risk of Monkeypox, such as avoiding contact with infected animals, practicing good hygiene, and using protective measures, helps prevent the spread of the virus.

- Fostering International Solidarity: Global collaboration and support for affected regions are essential. Wealthier nations and international organizations can provide financial aid, technical support, and resources to bolster local efforts and ensure a coordinated global response.

Conclusion & FAQs

Monkeypox, a zoonotic viral disease originally from Central and West Africa, has become a significant global health concern due to recent outbreaks extending beyond its traditional endemic regions. This poxvirus, related to smallpox but generally less severe, spreads through direct contact with infected animals, humans, or contaminated materials, with key vectors including rodents and primates. Human-to-human transmission occurs via close contact and respiratory droplets.

The disease typically starts with fever, headache, and muscle aches, followed by a distinctive rash that progresses through various stages, with an incubation period of 6 to 13 days. Accurate diagnosis relies on laboratory tests such as PCR, which are crucial for early detection and outbreak control. Preventive measures and vaccines, including those for smallpox, are vital in preventing Monkeypox, while treatment is mainly supportive, with antiviral medications like Tecovirimat under exploration.

Notable outbreaks, such as those in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and neighboring regions, underscore the importance of robust public health responses, global coordination, and community engagement. Addressing misconceptions and misinformation is crucial to prevent stigma and ensure accurate public understanding. As future outbreaks are possible, ongoing surveillance, research, and community involvement are essential for managing risks. Emphasizing awareness, prevention, and early intervention is critical for reducing transmission and severity.

Staying informed through reliable sources like the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and following health guidelines, is key to personal and community safety. By actively participating in vaccination programs and preventive practices, individuals can contribute to managing and mitigating the impact of Monkeypox, enhancing collective preparedness and resilience against the disease.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is Monkeypox?

Monkeypox is a zoonotic viral disease caused by the Monkeypox virus, a member of the Orthopoxvirus genus, which also includes the Smallpox virus. Initially identified in Central and West Africa, Monkeypox can cause symptoms similar to smallpox but is generally less severe. The illness is marked by fever, a rash, and enlarged lymph nodes.

How is Monkeypox transmitted?

Monkeypox spreads through direct contact with the blood, bodily fluids, or lesions of infected animals or humans. It can also be transmitted via contaminated materials like bedding or clothing. Human-to-human transmission occurs through close physical contact, including respiratory droplets, and during prolonged face-to-face interactions.

What are the symptoms of Monkeypox?

Monkeypox symptoms usually begin with fever, headache, muscle aches, and fatigue. After the initial symptoms, a rash develops, starting on the face and then spreading to other parts of the body. The rash progresses through stages of macules, papules, vesicles, pustules, and finally scabs. The incubation period ranges from 6 to 13 days, and symptoms can last between 2 to 4 weeks.

How is Monkeypox diagnosed?

Diagnosis of Monkeypox is confirmed through laboratory tests, including PCR (polymerase chain reaction) testing, which detects viral DNA in samples from lesions or other bodily fluids. Differential diagnosis is necessary to distinguish Monkeypox from other poxviruses and skin conditions.

Is there a vaccine for Monkeypox?

Yes, vaccines used for smallpox are effective in preventing Monkeypox. The JYNNEOS vaccine, specifically developed for Monkeypox and smallpox, is available and plays a crucial role in controlling outbreaks. Vaccination is crucial for those who are at an increased risk of exposure.

What treatments are available for Monkeypox?

There is no specific antiviral treatment for Monkeypox, but supportive care is crucial to manage symptoms. Antiviral medications like Tecovirimat (Tpoxx) are being studied for their effectiveness. Treatment aims to alleviate symptoms and avoid potential complications.

How can I prevent Monkeypox infection?

Preventive measures include avoiding contact with infected individuals and animals, maintaining good hygiene, and using personal protective equipment when necessary. Vaccination is recommended for those at risk, and avoiding contact with potentially contaminated materials is essential.

Are there any misconceptions about Monkeypox?

Common misconceptions include the belief that Monkeypox is a variant of smallpox or that it can be spread easily through casual contact. Monkeypox is distinct from smallpox and requires close contact for transmission. Addressing myths and misinformation helps prevent stigma and encourages accurate public understanding.

What is the current status of Monkeypox outbreaks?

As of recent reports, significant outbreaks have occurred in regions such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and neighboring countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) due to the widespread nature of recent outbreaks.

What role do public health organizations play in managing Monkeypox?

Public health organizations like the WHO and CDC play a vital role in managing Monkeypox outbreaks through surveillance, providing guidelines, coordinating international responses, and educating the public. They also support vaccination efforts and research to better understand and control the disease.