Introduction

Brief introduction to the topic

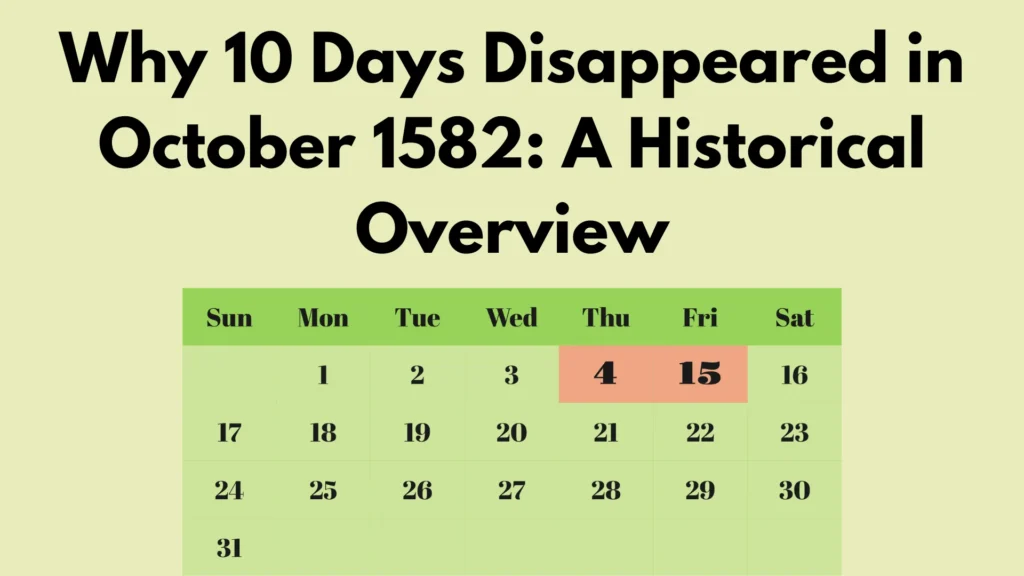

In October 1582, an extraordinary and unprecedented event took place: 10 days were erased from the calendar. This event was a result of the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, which replaced the Julian calendar that had been in use since 45 BCE. The reform was initiated by Pope Gregory XIII to correct discrepancies that had accumulated over centuries due to inaccuracies in the Julian calendar. This blog post explores the historical context, reasons behind the reform, and its significant impacts on timekeeping and society.

Importance of the October 1582 calendar change

The calendar change in October 1582 holds great significance for several reasons. First, it corrected the drift of the spring equinox, which had been gradually moving earlier in the year under the Julian calendar. This drift affected the timing of Easter, a central holiday in the Christian liturgical calendar, leading to inconsistencies with its intended alignment with the vernal equinox. By implementing the Gregorian calendar, Pope Gregory XIII aimed to realign the calendar with the solar year and restore the correct timing of Easter.

Additionally, the reform established a more accurate and consistent system for future timekeeping. This was crucial for various aspects of society, including agriculture, commerce, and historical record-keeping. The Gregorian calendar’s improved accuracy helped stabilize seasonal and religious events, providing a reliable framework for organizing time.

Background of the Julian Calendar

Introduction to the Julian Calendar

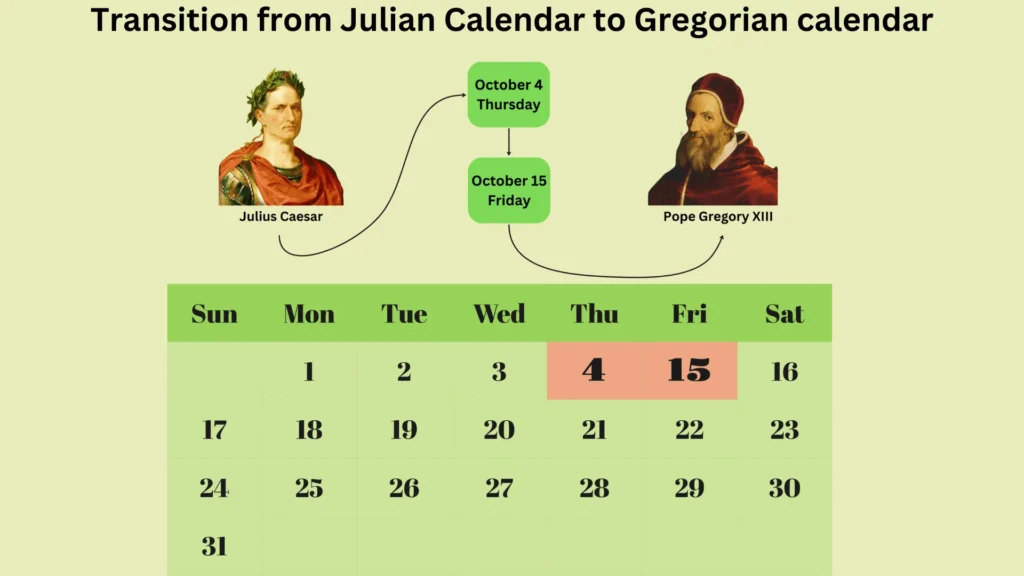

The Julian calendar, introduced by Julius Caesar in 45 BCE, was a reform of the Roman calendar, which was based on a lunisolar system. The Roman calendar had become increasingly misaligned with the solar year, causing confusion and inefficiencies in civil and agricultural activities. Julius Caesar, with the help of the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes, sought to create a more reliable and consistent calendar based on the solar year.

Explanation of Its Creation and Adoption

The Julian calendar was designed to approximate the solar year, which is about 365.25 days long. To achieve this, the calendar introduced a year of 365 days with an extra day added every four years, known as a leap year. This was a significant improvement over the Roman calendar, which had varied month lengths and frequent adjustments made by priests, often for political reasons.

Key features of the Julian calendar included:

- Standardized Month Lengths: The calendar had 12 months with fixed lengths: 30 or 31 days, except for February, which had 28 days in common years and 29 days in leap years.

- Leap Year Cycle: Every fourth year was designated a leap year, adding an extra day to February to account for the additional quarter of a day in the solar year.

- Consistent Year Length: The average year length in the Julian calendar was 365.25 days, which was a close approximation of the solar year.

The Julian calendar was adopted throughout the Roman Empire and became the predominant calendar in Europe. Its implementation helped standardize timekeeping and improved the alignment of the calendar with the seasons and agricultural cycles.

Issues and Inaccuracies in the Julian Calendar

It while a significant improvement over its predecessors, was not without its flaws. The primary inaccuracy stemmed from its method of accounting for the solar year. The Julian calendar assumed a year was 365.25 days long, achieved by adding an extra day every four years (leap year). However, the true length of the solar year is approximately 365.2425 days, or roughly 11 minutes and 14 seconds shorter than the Julian year.

This discrepancy, although seemingly minor on a yearly basis, compounded over time. Each year, the Julian calendar overestimated the length of the solar year by about 11 minutes. Over the centuries, this small error accumulated, causing the calendar to drift progressively out of alignment with the solar cycle and natural seasons.

The Need for Reform

The Effect of These Inaccuracies on the Calendar Over Centuries

The cumulative effect of the Julian calendar’s inaccuracies became increasingly problematic over the centuries. Since the calendar year was slightly longer than the actual solar year, the dates of important astronomical events, such as the equinoxes and solstices, began to shift. Specifically:

- Equinox Drift: By the 16th century, the spring equinox, which originally fell around March 21st during Caesar’s time, had drifted to around March 11th. This 10-day shift was significant for societies that relied on the timing of agricultural and religious activities according to the equinoxes.

- Seasonal Misalignment: The drift caused by the Julian calendar’s inaccuracies also affected the alignment of the seasons. Agricultural societies depended on the calendar to predict seasonal changes accurately for planting and harvesting crops. The drift could lead to agricultural practices falling out of sync with the natural growing seasons, potentially impacting food production and local economies.

- Cultural and Historical Records: The shift in the calendar dates over centuries also posed challenges for historians and scholars. Events documented according to the Julian calendar did not correspond accurately to their actual time in the solar year, leading to confusion in historical chronology and the interpretation of historical records.

The Impact on Seasons and Religious Observances

One of the most significant impacts of the Julian calendar’s inaccuracies was on religious observances, particularly Easter. The date of Easter is based on the vernal equinox and the phases of the moon. As the equinox drifted earlier in the calendar year, the timing of Easter became increasingly misaligned with the actual equinox.

- Easter Misalignment: By the 16th century, the vernal equinox was occurring around March 11th instead of March 21st. This misalignment caused discrepancies in determining the date of Easter, which traditionally falls on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the vernal equinox. The shift in the equinox date disrupted the calculation of Easter, leading to confusion and inconsistency in its observance across the Christian world.

- Liturgical Calendar: The drift in the calendar also affected other religious festivals and liturgical events that were tied to the solar year and the equinoxes. The liturgical calendar relied on the accurate timing of the equinoxes to maintain the proper sequence of feasts and holy days throughout the year.

- Church Reforms: The need to realign the calendar with the solar year and ensure the correct timing of religious observances became a major concern for the Catholic Church. Pope Gregory XIII recognized the necessity of reforming the calendar to address these issues and restore the proper alignment of the equinoxes, seasons, and religious festivals.

These combined effects of the Julian calendar’s inaccuracies on agricultural practices, seasonal alignment, and religious observances underscored the urgent need for a more accurate and reliable calendar system. This need led to the development and adoption of the Gregorian calendar, which aimed to correct the Julian calendar’s flaws and provide a more precise measure of time.

The Gregorian Calendar Introduction

Introduction to Pope Gregory XIII and His Role in the Reform

Pope Gregory XIII, born Ugo Boncompagni, ascended to the papacy in 1572. A scholarly pope with a deep interest in science and education, Gregory XIII was keenly aware of the inaccuracies plaguing the Julian calendar. By the time of his papacy, the drift between the calendar year and the solar year had grown to a concerning extent, causing significant misalignments in the dates of important religious observances, particularly Easter.

Pope Gregory XIII was motivated by the desire to restore accuracy to the calendar and ensure the proper timing of religious festivals. He recognized that the drift in the Julian calendar had not only ecclesiastical implications but also practical consequences for daily life and agriculture. To address this, he commissioned a committee of experts to develop a new calendar system that would correct the existing inaccuracies and prevent future drift.

The Objectives of the New Calendar System

The main objectives of the Gregorian calendar reform were:

- Realignment with the Solar Year: One of the primary goals was to realign the calendar with the solar year, ensuring that the dates of the equinoxes and solstices corresponded accurately to their astronomical occurrences. This realignment was crucial for maintaining the consistency of seasons and agricultural cycles.

- Correct Timing of Easter: Another critical objective was to correct the date of Easter. The misalignment of the vernal equinox under the Julian calendar had caused significant discrepancies in the calculation of Easter. The reform aimed to restore the timing of Easter to its intended position relative to the equinox.

- Long-Term Accuracy: The new calendar system needed to be more accurate and sustainable over the long term, minimizing the drift between the calendar year and the solar year. This required a careful adjustment of the leap year system and other calendar mechanics.

- Universal Adoption: Although initially intended for the Catholic Church, the Gregorian calendar was designed with the hope of eventual widespread adoption, improving consistency in timekeeping across different regions and cultures.

Key Changes Introduced in the Gregorian Calendar

The Gregorian calendar introduced several key changes to achieve its objectives:

- Leap Year Adjustment: The leap year rule was modified, which was the biggest alteration. The new system included a more precise rule for leap years:

- Basic Rule: A year is a leap year if it is divisible by 4.

- Exception to the Basic Rule: A year divisible by 100 is not a leap year.

- Exception to the Exception: A year divisible by 400 is a leap year.

- For Example:

- 1700, 1800, 1900: Not leap years (divisible by 100 but not by 400).

- 1600, 2000: Leap years (divisible by 400).

- Skipping 10 Days: October 1582 saw a 10-day leap in the Gregorian calendar to account for the cumulative drift. October 15, 1582, was the Friday that came after Thursday, October 4, 1582. This change fixed the drift caused by the Julian calendar and brought the calendar back into alignment with the spring equinox.

- Improved Calculation of Easter: The Gregorian calendar implemented a more accurate method for calculating the date of Easter. The new calculation was based on a more precise determination of the vernal equinox and the lunar cycle, ensuring that Easter would be observed on the correct Sunday after the equinox.

- New Year’s Day: The start of the new year was standardized to January 1, although this change was gradually adopted by different countries over time. Before the reform, various regions had different New Year’s Days, contributing to confusion and inconsistency.

- Adoption and Implementation: The Gregorian calendar was initially adopted by Catholic countries in 1582, including Italy, Spain, Portugal, and France. Its adoption spread gradually to Protestant and Orthodox countries, with some regions not fully transitioning until the 20th century. The calendar is now the internationally accepted civil calendar.

Why the 100-Year Rule?

The rule that a year divisible by 100 is not a leap year helps correct the overestimation of the length of the solar year in the Julian calendar:

- Divisible by 4: Adding an extra day every four years compensates for the 0.25-day difference per year.

- Not Divisible by 100: By skipping a leap year every 100 years, the calendar corrects for the fact that the solar year is slightly less than 365.25 days.

- Divisible by 400: Adding an extra day every 400 years further refines the calendar to account for the actual solar year being slightly longer than 365.24 days.

Mathematical Justification

- Julian Calendar Average Year Length: 365.25 days.

- Gregorian Calendar Adjustments: By having 97 leap years every 400 years instead of 100 (under the Julian system), the average year length becomes:

Average year length = 365 +(97/400) =365.2425 days

This closely approximates the actual solar year length of 365.2425 days, minimizing the drift between the calendar year and the solar year. Furthermore, if we take into account 0.2425 of a day and to convert it into hours, minutes, and seconds, follow these steps:

- Convert days to hours: 0.2425 days×24 hours=5.82 hours

- Separate the hours and the decimal part: 0.82 hours

- Convert the decimal part to minutes: 0.82 hours×60 minutes=49.2 minutes

- Separate the minutes and the decimal part: 49 minutes

- Convert the decimal part to seconds: 0.2 minutes×60 seconds=12 seconds

So, 0.2425 of a day is 5 hours, 49 minutes, and 12 seconds.

The introduction of the Gregorian calendar marked a significant improvement in timekeeping and addressed the long-standing inaccuracies of the Julian calendar. Its adoption ensured better alignment with the solar year and religious observances, providing a more reliable and consistent framework for organizing time.

The Missing 10 Days

Detailed Explanation of the Removal of 10 Days in October 1582

The most dramatic aspect of the Gregorian calendar reform was the removal of 10 days to correct the accumulated discrepancy caused by the Julian calendar’s overestimation of the solar year. This correction was necessary to realign the calendar dates with the actual positions of the Earth in its orbit around the Sun, ensuring that the vernal equinox would once again fall around March 21, as it had during the time of the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD.

The Julian calendar’s error of approximately 11 minutes per year had, over the centuries, resulted in a drift of about 10 days by the late 16th century. To remedy this, Pope Gregory XIII decreed that 10 days be removed from the calendar in October 1582. This adjustment was a one-time correction to eliminate the cumulative error that had built up over more than 1,600 years.

The Exact Dates Involved: October 4 to October 15

To implement this correction, the specific dates from October 5 to October 14, 1582, were skipped. This meant that Thursday, October 4, 1582, was immediately followed by Friday, October 15, 1582. This deletion of 10 days was necessary to bring the calendar back in line with the solar year and to ensure that the equinoxes and solstices occurred on their expected dates.

The Reason for Choosing October for the Adjustment

- Minimize Disruption to the Liturgical Calendar: October was selected because it was relatively free of major religious festivals or observances. The primary concern of the reform was to correct the date of Easter and other movable feasts tied to the vernal equinox. By choosing October, the adjustment had minimal impact on the liturgical calendar and the regular cycle of religious events.

- Agricultural Considerations: October was also a practical choice from an agricultural perspective. The harvest season was typically winding down, and major planting activities for the next cycle had not yet begun. This timing helped minimize the disruption to agricultural activities, which were closely tied to the calendar.

- Administrative Practicality: Implementing such a significant change required careful planning and coordination. By choosing October, the reformers had sufficient time after the decision to prepare for the adjustment and to communicate the change to the affected populations. This period also allowed for the necessary legal and administrative adjustments to be made.

- Historical Precedent: The calendar reform aimed to restore the date of the vernal equinox to around March 21, as it had been during the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD. This historical anchoring point was crucial for maintaining the consistency and accuracy of the Christian liturgical calendar, particularly the calculation of Easter.

The decision to implement the change in October was thus a well-considered choice that balanced the need for accuracy with the practical considerations of minimizing disruption to religious, agricultural, and administrative activities. The successful implementation of this correction paved the way for the widespread adoption of the Gregorian calendar, which remains the internationally accepted civil calendar today.

Implementation and Adoption

The Initial Implementation in Catholic Countries

The Gregorian calendar reform was initially implemented in Catholic countries starting in October 1582. Pope Gregory XIII issued the papal bull “Inter gravissimas” on February 24, 1582, which officially promulgated the new calendar. The bull outlined the changes to the leap year system, the adjustment of the date for Easter, and the deletion of 10 days in October 1582 to correct the accumulated drift.

The immediate adopters of the Gregorian calendar included:

- Italy: As the seat of the Papacy, Italy was among the first to adopt the new calendar. The implementation was smooth, with October 4, 1582, being followed directly by October 15, 1582.

- Spain and Portugal: These two countries, closely aligned with the Papacy, also adopted the calendar without delay. Spain’s vast empire, including its colonies in the Americas, followed suit, ensuring a wide initial adoption.

- France: King Henry III of France decreed the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, leading to the same 10-day adjustment in October 1582.

These Catholic countries adopted the reform swiftly, as adherence to the papal decree was seen as a demonstration of loyalty to the Church. The immediate change, while initially confusing to some, was generally accepted due to the authority of the Pope and the support of the ruling monarchs.

The Gradual Adoption by Other Countries Over the Following Centuries

The adoption of the Gregorian calendar by non-Catholic countries was gradual and spanned several centuries. Different political, religious, and cultural factors influenced the pace and manner of adoption:

- Protestant Countries: Initially, Protestant countries were hesitant to adopt the Gregorian calendar, viewing it as a Catholic innovation. However, the practical benefits and increasing discrepancies between the Julian and Gregorian calendars led to gradual adoption.

- Germany and the Netherlands: Protestant regions of Germany and the Netherlands adopted the Gregorian calendar in stages during the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

- Great Britain: In 1752, the Gregorian calendar was adopted by Great Britain and its American colonies. By then, there were eleven days separating the Julian and Gregorian calendars. Consequently, September 14, 1752, came after September 2, 1752.

- Scandinavia: Sweden adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1753, also adjusting by 11 days.

- Orthodox Countries: The Eastern Orthodox Church and the countries where it was predominant were more resistant to the Gregorian calendar due to religious and cultural differences.

- Russia: Russia continued using the Julian calendar until the Bolshevik Revolution. The Soviet government adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1918, aligning with Western Europe and the rest of the world.

- Greece: Greece adopted the Gregorian calendar for civil purposes in 1923, although the Orthodox Church continues to use the Julian calendar for liturgical purposes.

- Other Regions: Adoption in other parts of the world varied based on colonial influence and local decisions. For example, Japan adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1873 as part of its modernization efforts during the Meiji Restoration. China adopted it in 1912 after the fall of the Qing Dynasty, but full implementation took longer due to political instability.

Resistance and Controversies Surrounding the Calendar Change

The transition to the Gregorian calendar was not without resistance and controversy. Several factors contributed to the opposition:

- Religious Objections: Many Protestant and Orthodox Christians viewed the Gregorian calendar as a Catholic imposition. They resisted the change on religious grounds, fearing it would symbolize Papal authority over their churches and nations.

- Cultural Resistance: The calendar change disrupted traditional ways of life. The deletion of 10 days created confusion, especially for those with important events (such as birthdays or religious feasts) falling within the missing period. There were even myths and legends about people losing their lives, wages, or rents due to the skipped days, though these were largely exaggerated.

- Political Opposition: In some regions, political leaders resisted the change to assert their independence from the Papacy and Catholic influence. The adoption of the Gregorian calendar became entangled with nationalistic and anti-Catholic sentiments.

- Practical Challenges: Implementing the new calendar required updating legal documents, adjusting financial transactions, and re-educating the population. These practical challenges contributed to resistance and delays in adoption.

Despite these challenges, the Gregorian calendar gradually became the standard due to its improved accuracy and practicality. Today, it is the most widely used civil calendar worldwide, a testament to its enduring legacy and the success of the reform initiated by Pope Gregory XIII.

Impact and Consequences

Short-Term Impacts on Society, Commerce, and Daily Life

The introduction of the Gregorian calendar and the removal of 10 days in October 1582 had immediate and noticeable effects on society, commerce, and daily life:

- Confusion and Disruption: The abrupt removal of 10 days caused considerable confusion. People who had scheduled events, such as meetings, contracts, or personal milestones, found their plans disrupted. For instance, those with financial agreements or legal documents dated between October 5 and October 14 had to adjust their records, leading to potential disputes and complications.

- Economic Impact: Businesses and traders had to adapt to the new calendar system, which affected the timing of transactions and financial calculations. The adjustment period required recalibration of accounting practices, and the shift created a temporary disruption in economic activities.

- Administrative Adjustments: Governments and institutions had to update official records, documents, and calendars to reflect the new system. This process involved significant administrative work, including changing dates on documents, updating legal frameworks, and informing the public about the new calendar system.

- Cultural and Religious Observances: Religious and cultural celebrations that fell within the removed days were effectively lost for that year. This led to alterations in the timing of festivals and observances, which required adjustments and recalibrations to align with the new calendar system.

Long-Term Effects on Historical Records and Cultural Events

The Gregorian calendar reform had profound long-term effects on historical records and cultural events:

- Historical Chronology: The removal of 10 days introduced discrepancies in historical records. For historians, this shift created challenges in accurately dating events that straddled the transition period. The adjustment necessitated careful cross-referencing of dates to maintain historical accuracy.

- Consistency in Record-Keeping: The Gregorian calendar’s adoption provided a consistent framework for historical record-keeping. This uniformity helped synchronize dates across different regions and cultures, facilitating historical research and documentation.

- Cultural Continuity: Although the calendar changes initially disrupted cultural practices, it ultimately provided a stable framework for cultural events and holidays. Over time, the Gregorian calendar’s standardization allowed for consistent scheduling of annual celebrations, festivals, and religious observances.

- Impact on Science and Exploration: The Gregorian calendar reform contributed to scientific accuracy, particularly in astronomy and navigation. The improved alignment with the solar year enabled more precise observations and calculations, which were crucial for scientific progress and exploration.

The Current Status of the Gregorian Calendar Worldwide

Today, the Gregorian calendar is the most widely used civil calendar globally. Its adoption and status reflect its effectiveness and the long-term success of the reform:

- Global Adoption: Most countries worldwide use the Gregorian calendar for civil purposes. Its widespread acceptance is a testament to its accuracy and practicality. The calendar is used for business, government, education, and daily life, providing a consistent and standardized framework for organizing time.

- Religious and Cultural Variations: While the Gregorian calendar is predominant for civil and international use, some cultures and religious groups continue to use other calendars for specific purposes. For example, the Islamic calendar is used for Islamic religious observances, and the Jewish calendar is used for Jewish holidays. Additionally, traditional lunar and lunisolar calendars are still used in various cultural practices.

- International Standardization: The Gregorian calendar’s role as the international standard facilitates global communication, trade, and coordination. Its consistent framework supports international agreements, scheduling, and collaboration across different time zones and regions.

Conclusion

The calendar reform of October 1582, spearheaded by Pope Gregory XIII, was a pivotal moment in the history of timekeeping. The transition from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar, marked by the removal of 10 days, was driven by the need to correct inaccuracies and align the calendar with astronomical observations. This reform not only resolved long-standing discrepancies but also laid the foundation for a standardized system of timekeeping that continues to be used globally.

The importance of calendar accuracy cannot be overstated. Accurate timekeeping is essential for maintaining consistency in daily life, coordinating international activities, and preserving historical records. The Gregorian calendar’s adoption provided a reliable framework for organizing time, facilitating scientific progress, and supporting cultural continuity.

Reflecting on historical changes, we see how calendar reforms have shaped societies and influenced various aspects of life. The Gregorian calendar’s enduring legacy highlights the significance of accurate timekeeping and the impact of historical decisions on contemporary practices. The successful implementation and widespread adoption of the Gregorian calendar underscore the importance of precision and adaptability in managing time and aligning with the natural world.

Frequently Asked Question (FAQs)

Why were 10 days removed from the calendar in October 1582?

In October 1582, 10 days were removed to correct the discrepancy accumulated by the Julian calendar’s overestimation of the solar year. Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian calendar to realign the calendar with the solar year and ensure accurate timing of astronomical events, particularly the vernal equinox.

What was the impact of removing these 10 days on daily life?

The removal of 10 days caused confusion and disruption in daily life, commerce, and religious observances. People had to adjust their schedules, financial transactions, and historical records to align with the new calendar. Events and celebrations that fell within the removed days were effectively lost for that year.

How did the Gregorian calendar reform differ from the Julian calendar?

The Gregorian calendar introduced several key changes, including a more accurate leap year rule to better align with the solar year (365.2425 days), and the removal of 10 days to correct the drift that had accumulated over centuries. The Julian calendar had a slight discrepancy in the length of the year, leading to gradual misalignment with the seasons and astronomical events.

Why was October specifically chosen for the calendar adjustment?

October was chosen for the adjustment to minimize disruption to religious and cultural observances, as it was relatively free of major festivals and holidays. Additionally, the timing of the adjustment was practical from an administrative and agricultural perspective, avoiding major planting or harvest periods.

How did different countries adopt the Gregorian calendar?

Initially, Catholic countries such as Italy, Spain, Portugal, and France adopted the Gregorian calendar in October 1582. Protestant and Orthodox countries were slower to adopt the reform, with Great Britain and its colonies making the change in 1752 and Russia not adopting it until 1918. The calendar is now used globally for civil purposes, though some cultures continue to use other calendars for religious and traditional observances.

What were the controversies surrounding the Gregorian calendar reform?

The Gregorian calendar reform faced resistance due to its association with the Catholic Church. Protestant and Orthodox regions were reluctant to adopt it, viewing it as a Catholic imposition. There were also practical challenges and cultural disruptions as people had to adjust to the new system.

What is the current status of the Gregorian calendar worldwide?

Today, the Gregorian calendar is the most widely used civil calendar globally. It is employed for business, government, and everyday life in most countries. While some cultures and religions use other calendars for specific purposes, the Gregorian calendar remains the standard for international coordination and timekeeping.

Are there other significant calendar reforms besides the Gregorian calendar?

Yes, other notable calendar reforms include the French Revolutionary Calendar, which aimed to secularize timekeeping but was short-lived, and the adoption of the Gregorian calendar by various countries at different times. Additionally, the Islamic calendar and the Hebrew calendar have undergone their own adjustments to maintain accuracy and cultural relevance.