Introduction

Brief Introduction to Indian Philosophical Traditions

Indian philosophy is a rich tapestry of diverse thoughts and practices, spanning several millennia. It encompasses various schools of thought that address fundamental questions about existence, reality, knowledge, ethics, and the nature of the self. Major philosophical systems, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, are well-known globally. These traditions offer profound insights into metaphysical concepts, spiritual practices, and ways of living that have influenced not only Indian culture but also global philosophical and spiritual landscapes.

Indian philosophical traditions are broadly classified into two categories: orthodox (Astika) and heterodox (Nastika) schools. The orthodox schools include systems like Vedanta, Mimamsa, Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, and Vaisheshika, which generally accept the authority of the Vedas. The heterodox schools, which include Buddhism, Jainism, and the less-known Ajivika sect, reject the Vedic texts’ supremacy and often present alternative views on life, morality, and the universe.

Importance of Understanding Lesser-Known Sects

While Buddhism and Jainism have garnered significant attention for their unique approaches to spirituality and ethics, lesser-known sects like Ajivika offer equally intriguing perspectives. Understanding these lesser-known traditions is crucial for several reasons:

- Holistic View of Indian Philosophy: By studying a wider range of philosophical systems, we gain a more comprehensive understanding of the intellectual and spiritual diversity that characterizes Indian thought.

- Historical Context: Lesser-known sects provide context to the more dominant traditions, highlighting the dynamic and competitive nature of philosophical discourse in ancient India.

- Unique Contributions: These sects often introduce unique ideas and practices that challenge mainstream beliefs, enriching our understanding of human thought and spiritual exploration.

Overview of the Ajivika Sect and Its Significance

The Ajivika sect is one such lesser-known tradition that flourished in ancient India around the same time as Buddhism and Jainism. Founded by Makkhali Gosala, the Ajivikas proposed a deterministic view of the universe, emphasizing the concept of Niyati (destiny) as the primary force governing all events and actions. According to Ajivika doctrine, everything in life is predestined, and human effort has no influence over one’s fate.

The significance of the Ajivika sect lies in its radical departure from the notions of karma and free will, which are central to both Buddhist and Jain philosophies. While Buddhism and Jainism emphasize ethical actions and self-discipline as means to achieve spiritual liberation, the Ajivikas rejected the efficacy of personal effort altogether. This deterministic worldview posed profound questions about the nature of human existence, the role of ethics, and the meaning of life.

Despite its eventual decline, the Ajivika sect’s contributions to Indian philosophy are noteworthy. Their unique perspective challenged the prevailing beliefs of their time and offered an alternative understanding of life’s workings. Exploring the Ajivika sect not only sheds light on a forgotten chapter of philosophical history but also invites us to reflect on the varied ways humans have sought to comprehend their existence and place in the universe.

Historical Background

Origins of the Ajivika Sect

Founding by Makkhali Gosala

The Ajivika sect was founded by Makkhali Gosala, a contemporary of Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha) and Mahavira (the founder of Jainism). Makkhali Gosala is often described as a charismatic and influential spiritual teacher who gathered a significant following during his lifetime. According to various historical sources, including Buddhist and Jain texts, Gosala initially traveled with Mahavira and was a disciple before breaking away to establish his own path.

Gosala’s teachings centered around the concept of Niyati, or fate, which he proposed as the ultimate determinant of all events and actions. He argued that everything in the universe is predestined, and human effort cannot alter one’s destiny. This fatalistic doctrine was a significant departure from the karmic principles upheld by Buddhism and Jainism, which emphasize moral actions and personal responsibility.

Time Period and Geographical Context

The Ajivika sect emerged during the 5th century BCE, a period of significant intellectual and spiritual ferment in ancient India. This era, often referred to as the “Second Urbanization,” saw the rise of numerous philosophical and religious movements that challenged the orthodox Vedic traditions.

Geographically, the Ajivikas were primarily active in the regions of Magadha and Kosala, corresponding to parts of modern-day Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. These areas were major centers of political and cultural activity, with thriving urban settlements that provided fertile ground for diverse philosophical discourses. The Ajivikas established monastic communities and lived ascetic lifestyles, often in close proximity to other sects, facilitating interactions and exchanges of ideas.

Relationship with Other Contemporary Sects

The Ajivikas coexisted with several other prominent sects during their time, most notably Buddhism and Jainism. The interactions between these sects were marked by both intellectual exchanges and rivalry.

Buddhism

Buddhism and the Ajivika sect shared some commonalities, such as their rejection of Vedic authority and ritualistic practices. However, the two diverged sharply on key philosophical issues. While Buddhism emphasizes the importance of ethical conduct, meditation, and the potential for individuals to achieve enlightenment through their efforts, the Ajivikas’ deterministic view negated the role of personal effort in shaping one’s destiny.

The Buddhist texts often portray Makkhali Gosala in a critical light, reflecting the contentious relationship between the two traditions. For instance, the Samannaphala Sutta, part of the Digha Nikaya, categorizes the Ajivikas’ doctrine as a form of “nihilistic determinism,” contrasting it with the Buddha’s Middle Path.

Jainism

The relationship between the Ajivikas and Jainism is complex, given Makkhali Gosala’s early association with Mahavira. Jain texts recount the initial companionship between Gosala and Mahavira, followed by a dramatic schism. This split led to significant doctrinal differences, with Jainism advocating for rigorous asceticism, karma, and individual responsibility, in stark contrast to the Ajivika emphasis on predetermined fate.

Jain accounts, such as the Bhagavati Sutra, often depict Gosala as a misguided or heretical figure who deviated from the true path. Despite this, the Ajivikas shared some ascetic practices with the Jains, such as nudity and strict discipline, indicating a degree of mutual influence.

The Ajivika sect’s origins and its founder, Makkhali Gosala, reflect a period of rich philosophical diversity in ancient India. The sect’s distinctive doctrine of determinism set it apart from the more widely known teachings of Buddhism and Jainism, leading to both intellectual rivalry and philosophical debate. Understanding the historical background of the Ajivikas provides valuable insights into the complex and dynamic landscape of ancient Indian spirituality and thought.

Core Beliefs and Philosophies

Doctrine of Niyati (Destiny)

The cornerstone of Ajivika philosophy is the doctrine of Niyati, which translates to destiny or fate. According to this belief, every event in the universe is predestined and occurs according to an unalterable cosmic order. Makkhali Gosala, the founder of the Ajivika sect, taught that all experiences and actions—past, present, and future—are predetermined. This deterministic view asserts that the course of one’s life, including birth, suffering, pleasure, and death, is fixed by Niyati and cannot be changed by human effort or will.

Ajivikas believed that understanding and accepting this cosmic determinism could lead to a state of equanimity and peace. Since everything is preordained, individuals can relinquish their illusions of control and the anxiety that comes with it. This doctrine challenged the prevalent views of free will and moral responsibility, posing a stark contrast to the teachings of contemporary sects.

Views on Karma and Rebirth

In Buddhism and Jainism, the concepts of karma and rebirth are central. Both traditions hold that an individual’s actions (karma) directly influence their future lives and spiritual progress. In Buddhism, karma refers to intentional actions that affect one’s samsara (cycle of rebirth) and the potential attainment of Nirvana. Jainism also emphasizes the accumulation and purification of karma, advocating strict ethical conduct and ascetic practices to achieve liberation (moksha).

In contrast, the Ajivikas rejected the efficacy of karma in determining one’s fate. They argued that since everything is governed by Niyati, actions, whether good or bad, do not influence the cycle of rebirth or the individual’s future. This deterministic view negated the role of moral and ethical efforts in shaping one’s destiny. According to Ajivika philosophy, the cycle of rebirth is predetermined, and individuals will go through a fixed sequence of births and deaths regardless of their actions.

This perspective led to significant doctrinal conflicts with Buddhists and Jains, who saw moral discipline and ethical behavior as essential for spiritual liberation. The Ajivikas’ rejection of karma and moral agency was often criticized by other sects as nihilistic and potentially leading to moral indifference.

Concept of the Atman (Soul) in Ajivika Philosophy

The concept of the Atman, or soul, in Ajivika philosophy is also unique and integral to their worldview. Ajivikas believed in the existence of a permanent, unchanging soul that undergoes a predetermined series of rebirths. This Atman is not influenced by actions or ethical behavior but moves through its predestined path according to Niyati.

Unlike Buddhism, which denies the existence of a permanent soul and teaches the concept of Anatta (non-self), the Ajivikas maintained a belief in the eternal Atman. This aligns them more closely with certain Hindu and Jain views that recognize an enduring self. However, the Ajivikas diverged sharply in their interpretation of the soul’s journey and the factors influencing it. While Jainism advocates for the purification of the soul through righteous living and ascetic practices to attain liberation, the Ajivikas viewed the soul’s progression as fixed and unchangeable.

This belief in a predetermined soul journey reinforced their deterministic outlook, asserting that the soul’s experiences and final liberation are all predestined and not subject to personal effort or moral rectitude. The Ajivikas saw the understanding and acceptance of this truth as the path to spiritual serenity.

The core beliefs and philosophies of the Ajivika sect present a fascinating and radical departure from the more widely accepted doctrines of karma, moral agency, and spiritual progress in ancient Indian thought. By emphasizing the doctrine of Niyati (destiny), rejecting the influence of karma, and maintaining a unique concept of the Atman (soul), the Ajivikas offered a distinctive perspective on existence and the cosmos. These beliefs not only highlight the diversity of philosophical thought in ancient India but also challenge us to consider the implications of determinism and the nature of human agency in our own lives.

Practices and Lifestyle

Ascetic Practices of the Ajivikas

The Ajivikas were known for their rigorous ascetic practices, which were central to their spiritual discipline. Their daily routines and rituals were designed to reflect their deterministic beliefs and to cultivate a life of simplicity and self-denial.

Ajivika ascetics often led itinerant lives, moving from place to place without a permanent home. This wandering lifestyle symbolized their detachment from worldly possessions and societal structures. Their days were structured around meditation, reflection, and various austerities intended to discipline the body and mind.

One of the most notable aspects of Ajivika asceticism was their practice of nudity, which they saw as a rejection of material attachments and social conventions. By living without clothing, they aimed to transcend physical desires and societal norms. This practice was similar to certain Jain ascetics (Digambaras), who also embraced nudity as a form of spiritual discipline.

Additionally, Ajivikas practiced severe fasting and dietary restrictions, believing that such austerities would help them detach from the physical body and focus on their spiritual journey. They avoided harm to living beings as much as possible, aligning with their belief in predetermined cycles of rebirth and the inherent sanctity of all life forms.

Ethical and Moral Principles

While the Ajivikas’ deterministic worldview might suggest a disregard for ethics, they adhered to a set of moral principles that guided their conduct. Despite believing that human actions did not influence destiny, Ajivikas maintained high ethical standards as a means of living in harmony with their philosophical beliefs. Key ethical principles included:

- Ahimsa (Non-violence): Similar to Jains and Buddhists, Ajivikas practiced non-violence, avoiding harm to any living creature. This principle was reflected in their dietary habits and careful attention to avoid causing injury.

- Truthfulness: Ajivikas valued honesty and integrity in their speech and actions, considering it essential for spiritual purity.

- Non-possession: Embracing simplicity and minimalism, Ajivikas refrained from accumulating material possessions. This principle was evident in their practice of nudity and their itinerant lifestyle.

- Celibacy: Many Ajivika ascetics practiced celibacy, believing that renouncing sexual activity would aid in their spiritual focus and discipline.

These ethical guidelines were not seen as means to alter one’s destiny but as ways to align with the natural order and maintain inner peace and spiritual clarity.

Community Life and Organization

The Ajivikas lived in closely-knit monastic communities that provided structure and support for their ascetic practices. These communities were often organized around a central leader or teacher, who provided spiritual guidance and maintained the discipline of the group.

- Monastic Life: Ajivika monks and nuns adhered to strict communal rules, which included daily rituals, communal meals, and collective meditation sessions. These routines helped reinforce their ascetic commitments and fostered a sense of unity and purpose within the community.

- Itinerant Groups: As itinerants, Ajivikas traveled together in small groups, relying on alms and the support of lay followers for their sustenance. They established temporary shelters, often in secluded areas, where they could practice their austerities away from the distractions of urban life.

- Interaction with Lay Followers: Although primarily a monastic tradition, the Ajivikas also had lay followers who supported them with food and other necessities. These lay adherents respected the ascetics and sought to emulate their ethical principles, even if they did not fully adopt the ascetic lifestyle.

- Teaching and Transmission of Knowledge: Ajivika communities placed a strong emphasis on the oral transmission of their teachings. Senior monks and nuns taught younger members the doctrines and practices of the sect, ensuring the continuity of their philosophical heritage. They also engaged in debates and discussions with members of other sects, defending their views and refining their understanding of their own doctrines.

The practices and lifestyle of the Ajivikas were deeply intertwined with their philosophical beliefs, particularly their doctrine of determinism. Through rigorous ascetic practices, ethical conduct, and communal living, they sought to embody their understanding of a predetermined cosmos. The Ajivikas’ way of life, marked by simplicity, non-violence, and discipline, offers a unique perspective on how spiritual ideals can shape everyday practices and community structures. Their contributions to the tapestry of Indian spiritual traditions underscore the diversity and depth of ancient philosophical thought.

Influence and Legacy

Impact on Indian Philosophy and Religion

The Ajivika sect, although less known today, played a significant role in the development of Indian philosophy and religion during its peak. The Ajivikas introduced the radical concept of Niyati, or destiny, challenging the prevalent doctrines of karma and moral agency. This deterministic view pushed the boundaries of philosophical discourse and invited other sects to refine and defend their own teachings on free will, ethics, and the nature of existence.

- Philosophical Challenge: The Ajivikas’ emphasis on determinism forced other philosophical traditions, particularly Buddhism and Jainism, to address and counter the idea that all events are predestined and beyond human control. This interaction fostered a richer and more nuanced exploration of karma, free will, and moral responsibility.

- Ethical and Ascetic Practices: The rigorous ascetic practices of the Ajivikas influenced other ascetic traditions in India. Their emphasis on non-violence, celibacy, and renunciation found echoes in Jainism and certain Hindu sects. The Ajivikas’ lifestyle demonstrated the lengths to which spiritual seekers could go to embody their philosophical convictions.

- Social and Cultural Contributions: The presence of Ajivikas in the social and religious landscape contributed to the diversity of spiritual options available to people in ancient India. This diversity enriched the cultural and religious fabric of the time, providing alternative perspectives on spirituality and the pursuit of liberation.

Interaction and Conflicts with Other Sects

The Ajivikas coexisted with other major sects of the time, leading to both interactions and conflicts. These encounters were often marked by philosophical debates and occasional hostilities, reflecting the competitive nature of the religious landscape in ancient India.

- Debates with Buddhists: The most well-documented interactions between Ajivikas and Buddhists occurred in the context of philosophical debates. Buddhist texts often criticize the Ajivikas’ deterministic views, with figures like the Buddha himself engaging in debates to refute the idea of Niyati. For example, the Samannaphala Sutta recounts a discussion where the Buddha outlines the flaws in Makkhali Gosala’s deterministic doctrine, emphasizing the importance of ethical actions and personal effort.

- Conflicts with Jains: The relationship between Ajivikas and Jains was particularly complex, given Makkhali Gosala’s early association with Mahavira. Jain texts such as the Bhagavati Sutra describe the schism between Gosala and Mahavira, portraying Gosala in a negative light. These texts highlight doctrinal conflicts, particularly over the role of karma and the efficacy of ascetic practices. The Jains’ emphasis on karma and ethical conduct stood in stark contrast to the Ajivikas’ deterministic worldview, leading to significant ideological disputes.

- Royal Patronage and Decline: On account of its pessimistic philosophy this religion was not patronized by different rulers. Only Bindusara accepted this religion and even constructed some rock cut caves on Nagarjuna Hill or the Barabar Hills in Gaya. These caves were meant for residential purposes of Ajivika monks.

Decline and Disappearance of the Ajivika Sect

The decline of the Ajivika sect can be attributed to several factors, including the rise of more dominant religious traditions, the loss of royal patronage, and internal challenges.

- Dominance of Buddhism and Jainism: As Buddhism and Jainism gained more followers and institutional support, the Ajivikas found it increasingly difficult to maintain their influence. The well-established monastic systems and philosophical teachings of Buddhism and Jainism offered more comprehensive and appealing paths for spiritual seekers, leading to a gradual decline in Ajivika adherence.

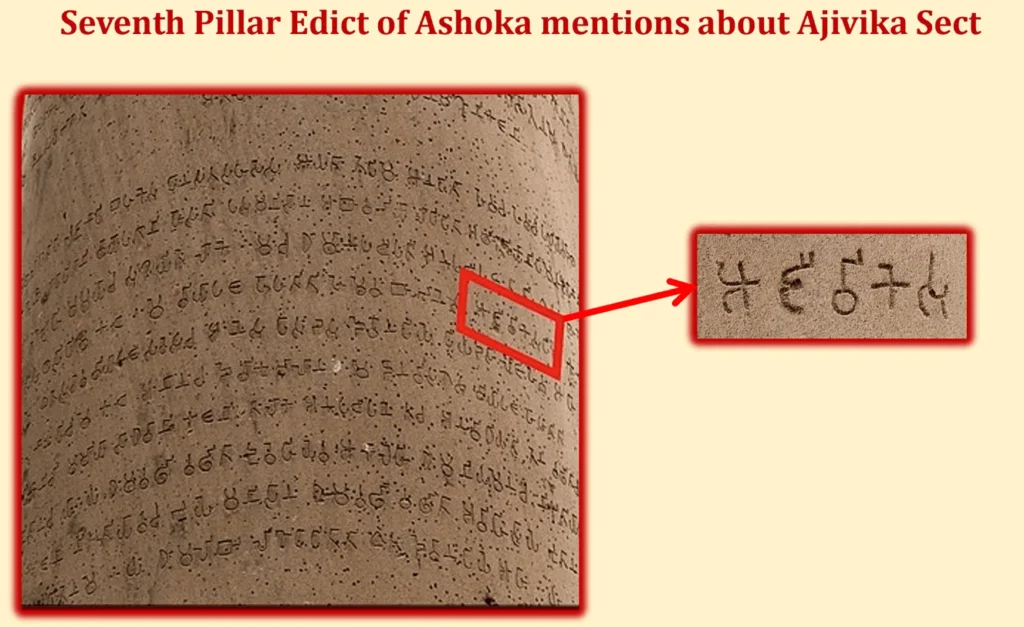

- Loss of Royal Patronage: The fluctuating support from royal patrons also contributed to the decline of the Ajivikas. While they enjoyed periods of patronage, such as under certain rulers like Ashoka, these were not sustained. The eventual withdrawal of royal support weakened their institutional structure and reduced their public visibility.

- Internal Challenges: Internal doctrinal rigidity and the extreme nature of their ascetic practices may have also played a role in their decline. The fatalistic doctrine of Niyati, while philosophically provocative, might have been less appealing to the broader population seeking practical ethical guidance and a sense of agency in their spiritual lives.

- Integration and Assimilation: Over time, some Ajivika ideas and practices may have been assimilated into other religious traditions, further diluting their distinct identity. Aspects of Ajivika asceticism and ethics found resonance in Jain and Hindu practices, leading to a gradual blending and loss of distinctiveness.

By the end of the first millennium CE, the Ajivika sect had largely disappeared as a distinct religious tradition. However, their legacy lives on through the historical records and the philosophical challenges they posed to their contemporaries, contributing to the rich tapestry of Indian spiritual and intellectual history.

The Ajivika sect’s influence on Indian philosophy and religion, their interactions and conflicts with other sects, and their eventual decline and disappearance tell a compelling story of a vibrant yet often overlooked tradition. By examining the Ajivikas’ unique doctrines, ascetic practices, and ethical principles, we gain a deeper appreciation for the diversity and complexity of ancient Indian thought. Their legacy, though not widely recognized today, underscores the dynamic interplay of ideas that has shaped the spiritual heritage of India.

Modern Relevance and Interpretation

Scholarly Interest and Research on the Ajivikas

The Ajivika sect, while largely forgotten in mainstream historical narratives, has attracted considerable scholarly interest in recent years. Researchers and historians have delved into ancient texts, inscriptions, and archaeological findings to reconstruct the beliefs, practices, and influence of the Ajivikas.

- Textual Analysis: Scholars have analyzed Buddhist and Jain scriptures, which often reference and critique Ajivika doctrines. These texts provide indirect yet valuable insights into Ajivika philosophy, highlighting the sect’s unique stance on destiny and determinism.

- Archaeological Evidence: Inscriptions and artifacts uncovered in regions like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh offer tangible evidence of Ajivika presence and practices. Notable among these is the Barabar Caves, which were donated by Emperor Ashoka to the Ajivikas. These ancient rock-cut caves provide clues about their monastic life and architectural preferences.

- Comparative Studies: Comparative research between Ajivika philosophy and other contemporary traditions has shed light on the intellectual exchanges and conflicts that shaped ancient Indian thought. Scholars examine how the Ajivikas’ deterministic worldview interacted with the doctrines of karma and ethical conduct upheld by Buddhists and Jains.

Lessons and Insights for Contemporary Spirituality and Philosophy

The Ajivikas’ emphasis on determinism and their ascetic practices offer several lessons and insights for contemporary spirituality and philosophy:

- Determinism and Free Will: The Ajivikas’ belief in an unalterable destiny invites modern thinkers to reconsider the balance between determinism and free will. Their philosophy challenges us to reflect on how much control we truly have over our lives and the extent to which our actions shape our destiny.

- Acceptance and Peace: The Ajivikas found peace in the acceptance of fate. In today’s fast-paced, achievement-oriented world, this perspective can offer a counterbalance, encouraging individuals to cultivate acceptance and equanimity in the face of life’s uncertainties.

- Ascetic Practices: The rigorous ascetic practices of the Ajivikas highlight the potential for simplicity and minimalism in spiritual growth. Modern movements towards minimalism and sustainable living resonate with the Ajivikas’ rejection of material excess and their focus on inner development.

- Ethics and Morality: Despite their deterministic beliefs, the Ajivikas upheld strong ethical principles. This paradox encourages contemporary philosophers to explore the foundations of morality and ethics beyond the framework of free will and personal responsibility.

Conclusion & FAQs

The Ajivika sect, founded by Makkhali Gosala, emerged as a significant yet often overlooked tradition in ancient Indian philosophy. Their core belief in Niyati, or destiny, set them apart from other contemporary sects like Buddhism and Jainism. The Ajivikas practiced rigorous asceticism, maintained high ethical standards, and lived in closely-knit monastic communities. Despite their decline, the Ajivikas’ contributions to philosophical discourse and their influence on other traditions were profound.

Studying the Ajivikas and other lesser-known philosophical traditions is crucial for gaining a comprehensive understanding of human thought and spirituality. It enriches our appreciation of the diverse ways in which cultures and societies have grappled with fundamental questions about existence, morality, and the nature of the self. Exploring these traditions broadens our perspective, challenges our assumptions, and deepens our insight into the human condition.

In an age where mainstream narratives often dominate our understanding of history and philosophy, it is essential to seek out and explore lesser-known traditions like the Ajivikas. By doing so, we not only honor the richness of our collective intellectual heritage but also discover alternative viewpoints that can inform and inspire our contemporary spiritual and philosophical pursuits. I encourage readers to delve deeper into the world of the Ajivikas and other forgotten traditions, embracing the diversity of thought that has shaped our world.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Who founded the Ajivika sect?

The Ajivika sect was founded by Makkhali Gosala, a contemporary of Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha) and Mahavira (the founder of Jainism). Makkhali Gosala was a charismatic spiritual teacher who initially traveled with Mahavira before establishing his own path centered around the doctrine of determinism.

What is the core belief of the Ajivika sect?

The core belief of the Ajivika sect is the doctrine of Niyati, or destiny. This doctrine asserts that everything in the universe, including human actions and experiences, is predestined and occurs according to an unalterable cosmic order. Ajivikas believed that fate governs all events, and that human effort cannot alter one’s destiny.

How did the Ajivika view karma and rebirth?

The Ajivikas rejected the traditional view of karma influencing one’s future lives, as upheld by Buddhists and Jains. They believed that all events and experiences, including the cycle of rebirth, are predetermined by Niyati. Thus, human actions do not impact one’s future destiny or the process of rebirth.

What were some of the ascetic practices followed by the Ajivikas?

Ajivikas practiced rigorous asceticism, including nudity, severe fasting, and dietary restrictions. They led itinerant lives, renounced material possessions, and adhered to a strict code of non-violence. These practices were intended to cultivate simplicity, detachment, and spiritual focus.

How did the Ajivikas differ from other contemporary sects like Buddhism and Jainism?

The Ajivikas differed from Buddhists and Jains primarily in their belief in determinism. While Buddhists and Jains emphasized karma and personal responsibility in shaping one’s destiny and spiritual progress, the Ajivikas maintained that everything is predetermined by fate. This fundamental difference led to significant doctrinal conflicts and philosophical debates.

What impact did the Ajivika sect have on Indian philosophy and religion?

The Ajivika sect had a notable impact on Indian philosophy by challenging prevailing ideas about free will, karma, and moral agency. Their deterministic worldview provoked other traditions to clarify and defend their own doctrines. The Ajivikas also contributed to the rich tapestry of ascetic practices and ethical principles in ancient Indian spirituality.

Why did the Ajivika sect decline and eventually disappear?

The decline of the Ajivika sect can be attributed to several factors, including the rise of more dominant religious traditions like Buddhism and Jainism, the loss of royal patronage, and internal challenges. Over time, the sect’s rigid determinism and extreme ascetic practices may have become less appealing to the broader population, leading to a gradual decline in followers.

Are there any remnants or influences of the Ajivika sect in modern times?

While the Ajivika sect itself has largely disappeared, its influence can still be seen in the historical and philosophical discourse of ancient India. Certain ascetic practices and ethical principles championed by the Ajivikas have parallels in modern movements toward minimalism, non-violence, and sustainable living. Scholarly interest in the Ajivikas continues to uncover insights into their contributions to Indian philosophy.

How can one learn more about the Ajivika sect?

To learn more about the Ajivika sect, one can explore ancient texts and scriptures from Buddhism and Jainism that reference Ajivika beliefs and practices. Additionally, archaeological findings such as the Barabar Caves offer tangible evidence of Ajivika monastic life. Scholarly works and comparative studies on ancient Indian philosophies also provide valuable insights into the Ajivikas’ unique worldview and historical significance.

What lessons can contemporary spirituality and philosophy draw from the Ajivika sect?

Contemporary spirituality and philosophy can draw several lessons from the Ajivika sect, including reflections on the nature of determinism and free will, the importance of acceptance and peace in the face of life’s uncertainties, and the value of ascetic practices for spiritual growth. The Ajivikas’ rigorous ethical standards and ascetic lifestyle also offer insights into the potential for simplicity and non-violence in modern spiritual pursuits.