Table of Contents

Introduction

The Satavahana Dynasty stands as one of the earliest and most influential post-Mauryan kingdoms in Indian history, marking a pivotal era in the political and cultural transformation of the Indian subcontinent. Flourishing between the 1st century BCE and the 3rd century CE, the Satavahanas established their dominance primarily in the Deccan region, encompassing present-day Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Telangana, and parts of Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, and Odisha. They served as a vital link between North and South India, laying the groundwork for later regional empires and fostering a sense of cultural unity across the subcontinent.

The Satavahana dynasty, which Simuka founded, successfully filled the political void in the Deccan plateau after rising from the ashes of the Mauryan Empire. Over the course of nearly four centuries, they evolved into a formidable power, demonstrating resilience in the face of foreign invasions and internal rivalries. Their reign is especially significant for its robust trade networks, monumental art and architecture, and the patronage of multiple religious traditions, including Brahmanism, Buddhism, and Jainism.

The Satavahanas were among the first Indian dynasties to issue coins with rulers’ names and portraits, a practice that influenced subsequent dynasties. Their inscriptions, primarily written in Prakrit and engraved in the Brahmi script, are valuable epigraphical sources for understanding ancient Indian society, economy, and governance. These records not only reflect the administrative sophistication of the Satavahana rulers but also underscore their commitment to upholding Dharma and preserving cultural continuity.

Geopolitically, the dynasty acted as a cultural and commercial bridge between the northern Indo-Gangetic plains and the peninsular south. They played a crucial role in maritime trade with the Roman Empire and Southeast Asia, which brought both economic prosperity and global recognition to ancient India.

In essence, the Satavahana Dynasty was more than just a ruling power—it was a civilizational force that shaped early Indian polity, art, religion, and commerce. Its legacy endures in the form of archaeological sites like Amaravati and Nagarjunakonda, literary traditions, and a political model that influenced later dynasties such as the Chalukyas and Rashtrakutas. Gaining an appreciation of India’s ancient past, particularly the dynamic and frequently overlooked history of the Deccan plateau, requires an understanding of the Satavahanas.

Historical Background

Post-Mauryan Political Vacuum in the Deccan

The decline of the Mauryan Empire around 185 BCE, following the assassination of the last Mauryan ruler Brihadratha by his general Pushyamitra Shunga, triggered a significant political fragmentation across the Indian subcontinent. While the Indo-Gangetic plains in the north saw the rise of successor states like the Shunga and Kanva dynasties, the Deccan region, spanning parts of present-day Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Karnataka, was left in a power vacuum. Tribal confederacies, semi-independent feudatories, and local chieftains replaced the centralized Mauryan authority that had once stretched far into the south.

This period of transition opened the door for indigenous powers to emerge and assert regional dominance. The Deccan, rich in natural resources and strategically located between northern India and southern trade ports, became a contested and vital zone. It is within this milieu that the Satavahanas, an ambitious dynasty with roots in the Deccan, rose to prominence.

Emergence of the Satavahanas as a Regional Power

The Satavahanas, also referred to in ancient texts as the Andhras, were among the earliest post-Mauryan dynasties to establish a stable, centralized rule in the Deccan. Unlike many other short-lived dynasties of the era, the Satavahanas not only survived the political chaos but also laid the foundation for a cohesive Deccan polity that lasted for nearly four centuries—from the 1st century BCE to the 3rd century CE.

Initially local feudatories or military governors under the Mauryas, the Satavahanas capitalized on the administrative experience and regional support they had accumulated. Their ability to mobilize local resources, form alliances with regional elites, and appeal to both Brahmanical and Buddhist traditions helped them consolidate control over a vast and culturally diverse territory.

What set the Satavahanas apart was their strategic diplomacy and military resistance against foreign incursions, particularly from the Western Kshatrapas and Indo-Scythians. Through successive campaigns, they not only defended the Deccan but also expanded into western and central India, gaining control of key trade routes and urban centers. Their military achievements, however, were closely linked to their cultural and administrative initiatives, making them one of the most balanced dynasties of their time.

Founder: Simuka – Establishing Satavahana Rule

The foundation of the Satavahana dynasty is traditionally attributed to Simuka, who is recognized as its first independent ruler. While historical records about him are sparse and often derived from Puranic texts, numismatic evidence and inscriptions corroborate his position as the dynasty’s progenitor.

Simuka is believed to have started his political journey in the late 2nd or early 1st century BCE, emerging from obscurity to unite fragmented tribal and regional communities under a single banner. He is credited with overthrowing the remnants of Mauryan and Nanda authority in the Deccan and establishing a new power center that respected both Brahmanical orthodoxy and local traditions.

One of Simuka’s enduring legacies was his commitment to restoring and patronizing Vedic rituals and institutions, which had experienced a decline under the more heterodox Mauryan patronage of Buddhism. Yet, his rule was not exclusive or intolerant—archaeological evidence suggests he also supported Buddhist monastic establishments, laying the foundation for the religious syncretism that would characterize the Satavahana period.

Simuka’s reign marked the transition from Mauryan bureaucracy to an indigenous Deccan-style monarchy, rooted in local legitimacy, regional alliances, and cultural pluralism. By establishing the dynasty’s capital at Pratishthana (modern-day Paithan in Maharashtra), he strategically positioned the Satavahanas at the crossroads of inland trade and spiritual networks, allowing his successors to build a lasting and influential empire.

The historical rise of the Satavahanas was not a mere political event—it was a civilizational moment for the Deccan region. From the ashes of the Mauryan Empire, the Satavahanas rose to provide administrative continuity, cultural patronage, and economic stability, beginning with the vision and leadership of Simuka. Their emergence reshaped the power dynamics of early India and created a legacy that would resonate across centuries.

Major Rulers of the Satavahana Dynasty

The Satavahana dynasty produced a succession of rulers whose reigns collectively shaped the political, economic, and cultural fabric of ancient India. While not all Satavahana kings are equally documented, several stood out for their military prowess, administrative reforms, trade facilitation, and cultural patronage. These rulers not only defended the Deccan from foreign invasions but also contributed to the unification and growth of early peninsular India.

Simuka – The Founder and Early Conquests

Simuka, the founder of the Satavahana dynasty, established the political foundations of what would become one of the most influential empires in the Deccan. Simuka, who arose in the aftermath of the Mauryan fall in the latter part of the second century BCE, capitalized on the chaos in the area and mobilized local support to oppose tribal confederacies and remaining Mauryan authority.

Though historical records are limited, Puranic accounts and early inscriptions confirm Simuka’s role in founding the Satavahana rule. He consolidated territories in the Krishna-Godavari basin, defeated rival local powers, and began the process of unifying the eastern and western Deccan. He was a known patron of Brahmanical rituals, yet archaeological evidence also suggests early engagement with Buddhist establishments, foreshadowing the dynasty’s religious tolerance.

Simuka’s reign laid the administrative and cultural framework that his successors would later build upon.

Satakarni I and II – Military Expansion and Consolidation

Satakarni I, who followed Simuka, was instrumental in extending Satavahana rule deep into the Narmada valley and even into parts of Malwa and western India. During his rule—possibly in the first century BCE—the Satavahanas changed from being a regional to a sub-imperial power. He is believed to have performed Vedic sacrifices like Ashvamedha, which not only legitimized his authority but also demonstrated his Brahmanical leanings.

This expansionist goal was continued by Satakarni II, who most likely governed in the early first century CE.His period saw increased political engagement with the Shakas and Western Kshatrapas, setting the stage for future conflicts and military triumphs under later kings. Satakarni II is also credited with strengthening inland trade routes and administrative structures, helping to stabilize the empire during its early growth phase.

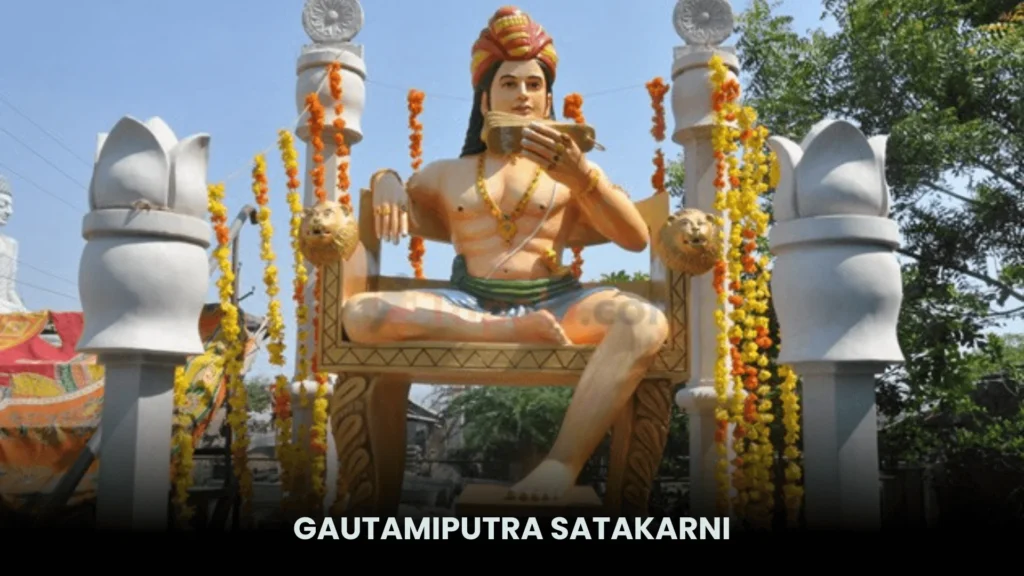

Gautamiputra Satakarni – The Zenith of Satavahana Power

Gautamiputra Satakarni (c. 78–102 CE), arguably the most famous of all Satavahana kings, brought the dynasty to its zenith. He is celebrated in inscriptions like the Nashik Prashasti, composed by his mother Gautami Balashri, which praises his conquests, governance, and religious adherence.

Conquests and Political Achievements:

Gautamiputra Satakarni achieved major military victories over the Shakas (Indo-Scythians), Yavanas (Greeks), and Western Kshatrapas, restoring Satavahana dominance in central and western India. His defeat of Nahapana, the Western Kshatrapa ruler, was particularly significant, reclaiming territories like Malwa, Gujarat, and northern Konkan, and reasserting indigenous control over key trade and cultural hubs.

Patron of Brahmanical Traditions:

Although his kingdom was religiously diverse, Gautamiputra presented himself as a staunch defender of Brahmanical dharma. He took pride in reviving traditional varna systems, supporting Vedic sacrifices, and promoting Brahmin settlements. Yet, his reign also allowed Buddhist institutions to flourish, highlighting a balanced policy of religious pluralism.

Gautamiputra’s leadership represents a harmonious blend of military strength, religious legitimacy, and imperial vision, often drawing comparisons with ancient India’s greatest emperors.

Pulumavi (Vasisthiputra Pulumavi): Urbanization, Maritime Power, and Commerce

Vasisthiputra Pulumavi, the son and successor of Gautamiputra Satakarni, continued his father’s legacy while shifting focus from military campaigns to economic consolidation and maritime expansion. His reign, around the mid-2nd century CE, marked a golden age of overseas trade.

Pulumavi established strong commercial ties with the Roman Empire, as evidenced by the discovery of Roman gold coins and amphorae in various Satavahana ports like Sopara, Koti, and Arikamedu. The first-century CE Greco-Roman travelogue The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea discreetly confirms the significance of Andhra’s marine trade during his rule.

Under Pulumavi, urban centers flourished, administrative efficiency improved, and religious patronage continued. His reign was one of cosmopolitan affluence as he backed Buddhist monasteries as well as Brahmanical temples.

Yajna Sri Satakarni – The Last Great Ruler

Yajna Sri Satakarni, often regarded as the last prominent ruler of the Satavahana dynasty, reigned during the late 2nd to early 3rd century CE. He was a formidable military leader, known for renewed conflicts with the Western Kshatrapas, against whom he achieved temporary victories, reclaiming parts of Maharashtra and Gujarat.

Yajna Sri Satakarni’s coinage shows ships and maritime symbols, indicating a strong emphasis on trade and seafaring prowess. The last blooming of Satavahana art and architecture also took place under his rule, particularly in Amaravati, a significant hub for Buddhist sculpture.

However, following his death, the dynasty faced internal disintegration, succession disputes, and increasing pressure from emerging powers like the Ikshvakus, Kadambas, and Pallavas. The empire fragmented into regional states, signaling the end of the Satavahana golden age.

The history of the Satavahana dynasty is best understood through the lens of its key rulers, each of whom contributed uniquely to its growth and endurance. From Simuka’s founding vision to Gautamiputra’s military zenith and Pulumavi’s commercial brilliance, the Satavahanas laid the blueprint for Deccan’s political, economic, and cultural identity for centuries. Their reign not only shaped early Indian statecraft but also left behind a legacy of artistic achievement, religious harmony, and administrative innovation that resonates in Indian history to this day.

Administration and Governance

The administrative framework of the Satavahana Dynasty reflects a sophisticated blend of centralized authority, regional autonomy, and cultural inclusivity. Ruling a vast territory with diverse linguistic, cultural, and geographic characteristics, the Satavahanas adopted a pragmatic and adaptive model of governance that laid the foundation for later Deccan empires.

Centralized Monarchy with Provincial Administration

At its core, the Satavahana polity was a hereditary monarchy, with the king (rajan) serving as the supreme authority in both civil and military affairs. The monarch was not just a political figurehead but a guardian of dharma, responsible for ensuring moral governance, justice, and prosperity.

Despite this central authority, the empire was divided into provinces or “Aharas”, which were administered by governors or local officials known as “Amatyas”. These regional units had a degree of administrative autonomy, especially in matters of revenue collection and law enforcement. This decentralized provincial system enabled effective governance across a diverse and expansive realm.

Urban centers such as Pratishthana (Paithan), Amaravati, and Nasik functioned as administrative and commercial hubs, often managed by guilds and merchant collectives under state supervision.

Matrilineal Influence in Royal Identity

One of the most distinctive features of the Satavahana administration was the matrilineal emphasis in royal inscriptions. Many Satavahana kings identified themselves through their mother’s lineage rather than the traditional patrilineal format. A more accurate rendering of the renowned royal name Gautamiputra Satakarni would be: “Satakarni, the son of Gautami,” highlighting the matronymic tradition where the mother’s name—Gautami—is honored in the ruler’s title.

This repeated acknowledgment of royal mothers, particularly in inscriptions and panegyrics, points to the significant social and political status of women in Satavahana society. While the overall system remained patriarchal, the matronymic naming convention suggests an elevated respect for maternal heritage, possibly influenced by local Deccan customs or a strategic move to legitimize the royal bloodline.

Coinage: Economic Symbols and Political Statements

The Satavahanas made notable contributions to numismatics, issuing a wide range of coins made of lead, potin (a bronze-like alloy), copper, and silver. Their coinage served not only as a medium of trade but also as a political and cultural instrument.

- The coins featured symbols such as ships, elephants, bulls, and swastikas, often accompanied by the king’s name in Prakrit language using Brahmi script.

- Inscriptions on coins helped standardize regional trade and bolstered the king’s image as a powerful and divine ruler.

- Bilingual and multicultural elements on some coins indicate extensive trade with foreign entities, including the Romans, and a dynamic, cosmopolitan economy.

These coins remain crucial sources for understanding chronology, economic policy, and territorial extent of the Satavahana realm.

Revenue System, Land Grants, and Taxation

To sustain a vast empire and support both religious institutions and public infrastructure, the Satavahanas maintained a structured revenue and taxation system.

- The primary source of income came from land revenue collected from farmers and landowners. Land was often measured, taxed, and redistributed through a system that resembled Mauryan precedents but was more regionally adapted.

- The Satavahana kings also issued land grants, especially to Brahmins and Buddhist monastic institutions, as a mark of religious patronage and state policy. These donative inscriptions, often found on cave walls and copper plates, serve as critical historical evidence.

- Taxes were also levied on trade, guilds, artisans, and maritime commerce, with tolls collected at ports and highways.

- In some cases, villages were gifted tax-free (agrahara grants), creating semi-autonomous religious or educational settlements.

This balance between centralized tax policy and religious gifting underscores a dual approach—statecraft rooted in pragmatism and legitimacy derived from dharmic principles.

Administration and Governance

The administrative framework of the Satavahana Dynasty reflects a sophisticated blend of centralized authority, regional autonomy, and cultural inclusivity. Ruling a vast territory with diverse linguistic, cultural, and geographic characteristics, the Satavahanas adopted a pragmatic and adaptive model of governance that laid the foundation for later Deccan empires.

Centralized Monarchy with Provincial Administration

At its core, the Satavahana polity was a hereditary monarchy, with the king (rajan) serving as the supreme authority in both civil and military affairs. The monarch was not just a political figurehead but a guardian of dharma, responsible for ensuring moral governance, justice, and prosperity.

Despite this central authority, the empire was divided into provinces or “Aharas”, which were administered by governors or local officials known as “Amatyas”. These regional units had a degree of administrative autonomy, especially in matters of revenue collection and law enforcement. This decentralized provincial system enabled effective governance across a diverse and expansive realm.

Urban centers such as Pratishthana (Paithan), Amaravati, and Nasik functioned as administrative and commercial hubs, often managed by guilds and merchant collectives under state supervision.

Matrilineal Influence in Royal Identity

One of the most distinctive features of the Satavahana administration was the matrilineal emphasis in royal inscriptions. Many Satavahana kings identified themselves through their mother’s lineage rather than the traditional patrilineal format. For example, the renowned Gautamiputra Satakarni literally means “Satakarni, son of Gautami.”

This repeated acknowledgment of royal mothers, particularly in inscriptions and panegyrics, points to the significant social and political status of women in Satavahana society. While the overall system remained patriarchal, the matronymic naming convention suggests an elevated respect for maternal heritage, possibly influenced by local Deccan customs or a strategic move to legitimize the royal bloodline.

Coinage: Economic Symbols and Political Statements

The Satavahanas made notable contributions to numismatics, issuing a wide range of coins made of lead, potin (a bronze-like alloy), copper, and silver. Their coinage served not only as a medium of trade but also as a political and cultural instrument.

- The coins featured symbols such as ships, elephants, bulls, and swastikas, often accompanied by the king’s name in Prakrit language using Brahmi script.

- Inscriptions on coins helped standardize regional trade and bolstered the king’s image as a powerful and divine ruler.

- Bilingual and multicultural elements on some coins indicate extensive trade with foreign entities, including the Romans, and a dynamic, cosmopolitan economy.

These coins remain crucial sources for understanding chronology, economic policy, and territorial extent of the Satavahana realm.

Revenue System, Land Grants, and Taxation

To sustain a vast empire and support both religious institutions and public infrastructure, the Satavahanas maintained a structured revenue and taxation system.

- The primary source of income was land revenue, collected from agriculturalists and landlords. Land was often measured, taxed, and redistributed through a system that resembled Mauryan precedents but was more regionally adapted.

- The Satavahana kings also issued land grants, especially to Brahmins and Buddhist monastic institutions, as a mark of religious patronage and state policy. These donative inscriptions, often found on cave walls and copper plates, serve as critical historical evidence.

- Taxes were also levied on trade, guilds, artisans, and maritime commerce, with tolls collected at ports and highways.

- In some cases, villages were gifted tax-free (agrahara grants), creating semi-autonomous religious or educational settlements.

This balance between centralized tax policy and religious gifting underscores a dual approach—statecraft rooted in pragmatism and legitimacy derived from dharmic principles.

The administration and governance of the Satavahana dynasty reveal a nuanced and adaptive state structure that balanced imperial authority with regional realities. Through a centralized monarchy, culturally significant matrilineal traditions, pioneering coinage, and a robust revenue system, the Satavahanas managed to rule effectively over a diverse and economically vibrant empire. Their model became a blueprint for subsequent Deccan powers, influencing governance, fiscal policy, and state-religion relations for centuries.

Economy and Trade

The Satavahana Dynasty, spanning nearly four centuries (1st century BCE to 3rd century CE), presided over one of the most dynamic periods of economic growth and commercial connectivity in ancient India. Their reign not only stabilized the Deccan politically but also transformed it into a vibrant economic corridor, linking inland markets with maritime trade routes that extended from Rome to Southeast Asia. The Satavahanas were astute rulers who understood that economic power was central to imperial strength, and they fostered an economic environment that encouraged urbanization, guild-based production, and transcontinental trade.

Inland and Maritime Trade Routes: The Andhra Coast as a Hub

The geographical location of the Satavahana Empire played a vital role in its commercial success. The Deccan plateau, nestled between the eastern and western coasts, allowed the Satavahanas to control strategic trade routes that connected North India with southern ports, and inland markets with international sea lanes.

The Andhra coast, in particular, emerged as a thriving maritime hub during the Satavahana period. From ports along the Krishna and Godavari rivers, goods were transported to interior markets through well-maintained roadways and riverine routes. Inland cities like Pratishthana (Paithan) and Ter (Tagara) became bustling trade centers, serving as intermediaries between rural producers and global traders.

The state encouraged commercial activities by maintaining security along trade routes, constructing storage facilities, and supporting merchant guilds (śreṇīs), which organized production, credit, and logistics across various sectors such as textiles, metallurgy, and pottery.

Important Ports: Koti, Sopara, and Connections to Rome and Southeast Asia

Several key ports under Satavahana control were directly involved in international maritime trade:

- Koti (modern-day Masulipatnam) and Motupalli were prominent ports along the eastern coast that facilitated trade with Southeast Asia, including regions like Burma, Thailand, and Vietnam.

- On the western coast, Sopara (modern Nala Sopara, near Mumbai) and Bharuch played an essential role in connecting India to the Roman Empire and Persian Gulf ports.

- The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a 1st-century CE Greco-Roman travelogue, explicitly references trade with regions corresponding to Andhra and the Deccan, highlighting the global significance of these ports.

Archaeological excavations at these sites have yielded Roman amphorae, coins, and ceramics, indicating frequent and prosperous foreign interactions. The presence of docks, warehouses, and large urban settlements near these ports further confirms the organized nature of trade under Satavahana rule.

Exports and Imports

The Satavahana economy was fueled by a rich exchange of high-value commodities, catering to both domestic consumption and international markets:

- Major Exports

- Spices: Pepper, cardamom, and turmeric—essential in Roman kitchens and medicine.

- Textiles: In Asia and the Mediterranean, there was a great demand for cotton textiles and muslins, especially from Tagara and Paithan.

- Pearls and Precious Stones: Collected from coastal and riverine regions and exported as luxury items.

- Ivory, tortoiseshell, sandalwood, and lacquerware, all featured prominently in Indo-Roman trade.

- Key Imports

- Wine and Olive Oil: From Roman provinces.

- Glassware and Ceramics: Distinctively Roman styles found in excavations at Arikamedu and Nasik.

- Gold and Silver Coins: Flowed into India in exchange for its exports, boosting domestic liquidity and luxury consumption.

This robust trade network not only enriched the Satavahana treasury but also fostered urban growth, increased social mobility, and spurred artistic innovation, particularly in regions where merchant guilds funded stupas, temples, and monasteries.

Use of Punch-Marked and Roman Coins: Currency as Cultural Exchange

The Satavahanas adopted and circulated a wide variety of coinage to support this expanding economy. Their monetary system was characterized by:

- Punch-marked coins made of lead, copper, and potin (a tin-based alloy), often bearing regional symbols like ships, swastikas, and elephants.

- Inscriptions were in Prakrit, although they were typically written in the Brahmi script, showing a deliberate effort to employ informal language for business and administrative inclusion.

- Roman gold aurei and silver denarii have been discovered in Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra, often alongside Satavahana coins. These were not only used in commerce but also melted down and reissued, blending Indo-Roman monetary systems.

- Coin hoards suggest that Satavahana ports became de facto financial centers, where both domestic and foreign currencies circulated freely, encouraging long-distance trade.

Coinage thus served a dual purpose—facilitating economic transactions and projecting political legitimacy. Satavahana identity, authority, and interaction with the wider ancient world were reflected in the iconography and inscriptions.

The Satavahana Dynasty’s economic legacy is a testament to their visionary statecraft and maritime ambition. By leveraging inland trade routes, developing port infrastructure, engaging in transcontinental commerce, and issuing accessible coinage, they created an economic network that extended far beyond the Indian subcontinent. Their success in balancing domestic production with international demand helped shape the early Indian Ocean trade system, making the Satavahanas not just rulers of the Deccan—but key architects of globalized commerce in antiquity.

Art and Architecture of the Satavahana Dynasty

The Satavahana Dynasty (circa 1st century BCE to 3rd century CE) not only reigned as a formidable political and economic force in the Deccan but also catalyzed a significant cultural and artistic transformation that laid the foundations for early Indian art and architecture. Their reign marked an era of aesthetic vibrancy, religious patronage, and syncretic creativity that would influence the subcontinent for centuries.

Royal Patronage to Buddhist Art and Architecture

The Satavahanas were known for their profound patronage of Buddhism, particularly the Hinayana (Theravada) school. Their support extended to the construction of grand monasteries, stupas, chaityas (prayer halls), and viharas (monastic complexes) throughout their domain. Kings, nobles, merchants, and lay devotees often sponsored these architectural projects, reflecting both religious devotion and socio-political legitimacy.

- The rulers frequently donated land and wealth to Buddhist institutions.

- Many inscriptions from their period, especially in Brahmi script and Prakrit language, attest to donations made for the maintenance and expansion of Buddhist establishments.

- Women, especially queens and mothers of kings (a matrilineal nuance in Satavahana polity), also played a visible role in patronage.

This widespread and inclusive encouragement turned the Deccan region into a thriving hub of Buddhist cultural activity.

The Amaravati School of Art: A Flourishing Aesthetic Tradition

The Amaravati School of Art is the Satavahanas’ most renowned creative output. Flourishing primarily in the Andhra region, this school gave rise to a distinctive style of sculpture and relief work that combined narrative dynamism with refined elegance.

- Characteristics:

- Sculptures were made predominantly in limestone.

- High relief carvings with deep undercutting brought narrative scenes to life.

- The Jataka stories, the Buddha’s life events, lotus medallions, and celestial beings were among the motifs.

- The poses and details of the figures were lifelike, elegant, and very expressive.

Unlike the rigid symmetry of earlier Mauryan art, Amaravati artists introduced fluid movement and emotional expression in their works, indicating a transition toward classical Indian artistic sensibilities.

Stupas and Religious Centers

During the Satavahana period, a number of imposing stupas were built and renovated, serving as hubs for religious and cultural interaction.

- Amaravati Stupa (present-day Andhra Pradesh):

- Originally built in the 2nd century BCE, it was enlarged and artistically enriched under Satavahana patronage.

- Once stood as a massive structure with intricately carved railings, drum slabs, and dome panels depicting Jataka tales and symbolic representations of Buddha.

- Nagarjunakonda:

- An archaeological treasure trove, this site flourished under the later Ikshvakus (who succeeded the Satavahanas) but retained strong Satavahana influences.

- Included art that combined Amaravati and Gandharan styles, stupas, and a sizable monastic complex.

- Jaggayyapeta Stupa:

- Situated in Krishna district, Andhra Pradesh, this early stupa features elaborate carvings and inscriptions linked to the Satavahana era.

- Highlights the early phase of the Amaravati School and reveals deep religious ties between art, society, and governance.

These stupas were not just centers of worship but also served as social, educational, and artistic hubs—attracting monks, pilgrims, sculptors, and patrons.

Influence on Early Indian Sculpture and Iconography

The artistic legacy of the Satavahanas played a pivotal role in shaping the trajectory of Indian sculpture and religious iconography, leaving a lasting influence on the aesthetic sensibilities of subsequent dynasties.

- Introduced the narrative technique—multiple scenes from a single story depicted in one panel, influencing later Hindu and Jain art.

- Contributed to the development of symbolic representation of divine figures. Buddha, for instance, was represented via symbols like the Bodhi tree, wheel, and footprints—a hallmark of early Buddhist art.

- Pioneered a dynamic fusion of idealism and realism that greatly influenced following artistic schools like Sanchi, Mathura, and the Gupta style.

The Satavahana visual culture thus served as a bridge between the aniconic phase of early Indian art and the anthropomorphic depictions of the classical period.

The art and architecture under the Satavahana dynasty embody a golden chapter in India’s cultural heritage. The Satavahanas enhanced the aesthetic fabric of the Indian subcontinent by supporting Buddhist institutions, encouraging the development of religious architecture, and cultivating a distinctive sculpture culture in Amaravati. Their artistic endeavors were not merely expressions of piety but tools of diplomacy, statecraft, and social cohesion—echoing their vision of a culturally integrated and spiritually enriched realm. As eternal representations of India’s ancient artistic inventiveness, the surviving pieces of their artistic legacy nevertheless arouse admiration and academic curiosity today.

Religion and Society under the Satavahanas

Religious Pluralism and Patronage

The Satavahana Dynasty (c. 1st century BCE – 3rd century CE) stood out for its remarkable religious tolerance and pluralistic governance, setting a precedent in the Deccan for centuries to come. The Satavahana rulers extended royal patronage to Brahmanism, Buddhism, and Jainism, recognizing the diverse spiritual fabric of their empire.

- Under the Satavahanas, Brahmanism, which has its roots in Vedic traditions, gained popularity. Rituals like Ashvamedha Yajna were revived, and Brahmins were generously endowed with land grants (agraharas), ensuring their economic and religious autonomy.

- Buddhism flourished alongside Vedic practices, with substantial royal and merchant-class patronage for the construction of monasteries (viharas) and stupas across the Deccan plateau. Key Buddhist centers like Amaravati, Nagarjunakonda, and Jaggayyapeta rose to prominence under Satavahana rule.

- Jainism, though less prominent, also found support, especially among the merchant communities who were integral to the dynasty’s expansive trade networks.

This syncretic patronage not only reflects the rulers’ inclusive approach but also indicates a nuanced understanding of religion as a unifying and stabilizing force in governance.

Coexistence of Vedic Rituals and Buddhist Monastic Culture

The religious life of Satavahana society was marked by dual spiritual currents. On one hand, Vedic rituals and sacrificial rites were performed to assert political legitimacy and divine sanction. On the other, Buddhist monasteries served as centers of learning, philosophy, and spiritual guidance for the masses.

Notably, Gautamiputra Satakarni is known to have performed elaborate Vedic sacrifices like the Rajasuya and Vajapeya, indicating his role as a dharmic king (dharma-rāja). Simultaneously, his era also saw heightened activity at Buddhist centers, signifying a symbiotic relationship between orthodoxy and reformist faiths.

Social Structure and Role of Women

Satavahana society was hierarchical but displayed notable deviations from the rigid varna system observed in northern India.

- The society broadly followed varna-based stratification, but inscriptions suggest a fluid interaction among classes, especially due to trade, urbanization, and religious movements.

- Uniquely, the dynasty reflected matrilineal influences in royal titulature. Many Satavahana kings, such as Gautamiputra Satakarni, attributed their lineage not just to their fathers but to their mothers (Gautami Balashri), highlighting the high status of women in certain spheres of society.

- Women also played roles as donors, patrons of religious art, and participants in trade and temple activities. Inscriptions at sites like Nagarjunakonda and Amaravati mention female donors, suggesting their economic and social agency.

Literary Contributions and Prakrit Inscriptions

The Satavahanas played a significant role in nurturing Prakrit literature, which served as the lingua franca across much of their empire.

- The use of Prakrit in Brahmi script for official inscriptions, such as those found at Nasik, Karle, and Amaravati, indicates an effort to communicate with a broad base of society beyond the elite Sanskrit-using class.

- These inscriptions are rich historical sources, providing insights into administration, religion, commerce, and philanthropy.

- Literary works like the Gāthāsaptaśatī, a compilation of Prakrit verses attributed to Hāla, a Satavahana ruler, reflect the refinement of courtly life and aesthetics, especially in the realm of love and nature poetry.

Religion and society during the Satavahana era reveal a harmonious confluence of tradition and transformation. By embracing diverse faiths, endorsing both Vedic and non-Vedic traditions, and recognizing the agency of women and commoners in cultural life, the Satavahanas forged a resilient and inclusive society. Their legacy not only influenced later dynasties in the Deccan but also laid the cultural and religious foundation for centuries of South Indian polity.

Decline of the Satavahana Dynasty

From the first century BCE until the third century CE, the Satavahana dynasty—one of the most powerful post-Mauryan Indian powers—was at its height. However, like all great empires, it eventually succumbed to a combination of internal decay and external pressure. The decline of the Satavahanas marks a pivotal transitional phase in the Deccan’s political landscape, ushering in the emergence of regional kingdoms and a new socio-cultural order.

Internal Conflicts and Weak Successors

A significant factor in the dynasty’s downfall was political instability and succession disputes. After the reign of powerful emperors like Gautamiputra Satakarni and Yajna Sri Satakarni, the dynasty witnessed a series of weak and ineffectual rulers. These later monarchs struggled to assert authority across the vast territories governed by their predecessors.

The centralized monarchy, which had once effectively coordinated administration and military campaigns, began to lose its grip. The frequent division of the kingdom among successors, a practice that might have stemmed from regional pressures and matrilineal influences, weakened the integrity of the empire.

Moreover, nobility and provincial governors started acting autonomously, further undermining royal authority. This fragmentation at the center created fertile ground for rival claimants and diminished the dynasty’s ability to resist external threats.

Invasions by Western Kshatrapas and the Rise of Foreign and Regional Powers

The Western Kshatrapas (or Saka Kshatrapas), who had earlier been subdued by Gautamiputra Satakarni, gradually regained power in western India, especially in Gujarat and Malwa. Their resurgence in the 3rd century CE posed a serious military and economic threat to the Satavahanas.

These Kshatrapas, led by rulers like Rudrasimha I, began encroaching into Satavahana territories, engaging in territorial disputes that further strained the already-weakened central administration. The Satavahanas could not mount a unified defense due to their dwindling resources and internal divisions.

At the same time, foreign trade routes—vital to the Satavahana economy—started shifting under the control of new maritime powers and emerging regional centers, affecting economic stability.

Fragmentation into Smaller Kingdoms

With the weakening of the central Satavahana authority, several regional dynasties emerged to fill the political vacuum. Among the most notable were:

- The Ikshvakus in Andhra Pradesh, who established themselves as powerful patrons of Buddhist culture and took over important trade centers previously under Satavahana control.

- The Pallavas, who rose in prominence in the southern regions, particularly around modern-day Tamil Nadu, initiating a new phase of temple architecture and regional polity.

- The Abhiras and Vakatakas, who asserted control in western and central India respectively.

These successor states retained elements of Satavahana administration, coinage, and cultural policies, but governed independently, marking the end of Satavahana imperial unity.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Though the Satavahana Empire dissolved by the early 3rd century CE, its impact endured:

- Their coinage system influenced subsequent dynasties.

- Patronage of Buddhist monuments and the Amaravati School of Art laid the foundation for sculptural traditions in southern India.

- The promotion of Prakrit language and literature, along with inscriptions, ensured their memory in historical records.

The decline of the Satavahana dynasty was not abrupt but rather a gradual process shaped by internal fragmentation, succession disputes, weakening trade control, and external invasions. Despite their fall, the Satavahanas served as a crucial bridge between the Mauryan age and the rise of powerful Deccan and South Indian empires like the Chalukyas and Pallavas. Their legacy remains enshrined in India’s art, architecture, and early regional state formation.

Legacy and Historical Importance of the Satavahana Dynasty

The Satavahana dynasty, which reigned predominantly between the 1st century BCE and 3rd century CE, holds a place of immense significance in Indian history—not merely as a ruling power, but as a cultural and administrative bridge between the northern and southern regions of the subcontinent. Their enduring legacy is reflected across India’s historical, economic, religious, and artistic dimensions.

Cultural Integration of North and South India

One of the most profound impacts of the Satavahana rule was the seamless fusion of Aryan (Indo-Aryan) and Dravidian cultural elements. Positioned strategically in the Deccan, the Satavahanas acted as cultural intermediaries. Their court adopted Sanskrit and Prakrit alongside regional dialects, fostering a linguistic synthesis that lasted centuries.

- Administrative Synthesis: Their governance model reflected northern traditions such as the use of Brahmanical rituals, yet they adapted it to suit local Dravidian contexts.

- Inter-regional Marriages: Satavahana rulers often formed matrimonial alliances with northern and southern dynasties, further encouraging social cohesion.

This cross-cultural connectivity laid the groundwork for a more unified Indian cultural identity in the early historical period.

Foundation for Later Deccan Empires

The Satavahanas were not just precursors but architects of political organization in peninsular India. Their administrative and economic models directly influenced subsequent Deccan empires like the Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas, and Vakatakas.

- Decentralized Feudal Administration: The Satavahanas employed a feudal system of governance by delegating authority to local feudatories—many of whom later rose to power after the dynasty’s decline.

- Religious Pluralism as Policy: The religious tolerance practiced by the Satavahanas became a hallmark of many later empires, especially the Chalukyas and Pallavas.

Their legacy was not only institutional but also spiritual and intellectual, forming the bedrock of Deccan’s future glory.

Significant Source for Understanding Ancient Indian Economy and Polity

Modern scholars heavily rely on the economic and political blueprint of the Satavahanas to understand ancient India’s dynamics. Their era offers one of the richest corpora of material and literary evidence.

- Numismatic Evidence: Satavahana coins—especially punch-marked and Roman coins—reveal thriving internal and international trade. These coins aid in tracking the movement of wealth and products, particularly during the Roman Empire.

- Inscriptions and Grants: The dynasty left behind a wealth of Prakrit inscriptions, detailing land grants, tax policies, and social organization. They provide invaluable insights into the early structure of statecraft in India.

Through these records, historians are able to piece together a realistic and nuanced picture of India’s early economic and political frameworks.

Contributions to Art, Literature, and Maritime Trade

The Satavahanas were not mere administrators—they were patrons of culture, enabling India to flourish artistically and economically.

- Art and Architecture: Their support for Buddhist institutions led to the creation of the Amaravati School of Art, which influenced Indian sculpture for centuries. The stupas at Nagarjunakonda and Amaravati are UNESCO-level heritage sites today.

- Literature: The widespread use of Prakrit in inscriptions made administrative communication accessible to the common people and nurtured a vernacular literary tradition.

- Maritime Trade Expansion: Ports such as Sopara, Koti, and Masulipatnam flourished under their watch, establishing trade with Rome, Egypt, and Southeast Asia. The Satavahanas were crucial in embedding India into the global ancient maritime network.

Their support of cross-border trade and cultural production marked India’s first golden age of global interaction.

The Satavahana dynasty’s legacy transcends their time and territory. As connectors of India’s geographical and cultural halves, architects of economic prosperity, and patrons of art and pluralism, their contributions continue to be foundational in Indian historiography. Their rule not only shaped the socio-political structure of the Deccan plateau but also served as a cultural crucible that nurtured a distinctive Indian identity—one that resonated across oceans and millennia.

Conclusion & FAQs

The Satavahana Dynasty stands as a remarkable chapter in ancient Indian history, not just for its political longevity but for its enduring cultural, economic, and artistic contributions. Emerging in the Deccan after the decline of the Mauryan Empire, the Satavahanas played a transformative role in shaping the historical and political landscape of peninsular India. They served as a cultural and economic bridge between the North and South, facilitating the integration of Vedic traditions with local beliefs, while also nurturing Buddhism and Jainism through royal patronage. Their rule marked a period of remarkable tolerance and pluralism, evident in the peaceful coexistence of Brahmanical rituals and Buddhist monastic life.

Economically speaking, the Satavahanas played a key role in developing marine trade, which linked India with Southeast Asia, the Roman Empire, and other regions. The strategic use of Prakrit in inscriptions and administration also demonstrates their commitment to regional inclusivity, fostering a sense of collective identity across linguistic and ethnic boundaries.

Architecturally, their legacy lives on through stunning stupas at Amaravati, Nagarjunakonda, and Jaggayyapeta, which influenced subsequent Indian art for centuries. Furthermore, their administrative framework, coinage system, and emphasis on trade laid the groundwork for later Deccan empires such as the Chalukyas and Rashtrakutas.

In a broader narrative, the Satavahanas represent the resilience and innovation of early post-Mauryan India, navigating internal challenges and external threats with adaptability and vision. Their contributions continue to inform modern understandings of ancient Indian polity, society, and cultural synthesis, making them an indispensable subject of historical inquiry and admiration.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Who founded the Satavahana Dynasty?

The founder of the Satavahana Dynasty is believed to be Simuka, who established the rule around the 2nd century BCE, shortly after the decline of the Mauryan Empire.

What were the key capitals of the Satavahana Empire?

The major capitals were Pratishthana (modern-day Paithan in Maharashtra) and Amaravati (in Andhra Pradesh), both of which were important centers for administration and trade.

Which languages did the Satavahanas use for administration and inscriptions?

The Satavahanas predominantly used Prakrit, written in the Brahmi script, for their official inscriptions, setting them apart from the Sanskrit usage of later dynasties.

What religion did the Satavahana rulers follow?

Although they were primarily followers of Brahmanism, the Satavahanas showed exceptional religious tolerance, also supporting Buddhism and Jainism. Several kings performed Vedic sacrifices while simultaneously funding Buddhist monasteries.

What is the significance of the Amaravati School of Art?

The Amaravati School of Art, which flourished under the Satavahanas, is renowned for its detailed relief sculptures, dynamic human figures, and expressive storytelling, primarily seen on Buddhist stupas and railings.

How did the Satavahanas contribute to trade?

They were instrumental in developing maritime trade networks, linking the Indian subcontinent with Rome, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. Their port towns and coinage facilitated vibrant commerce.

Why did the Satavahana Dynasty decline?

The dynasty declined due to a mix of internal succession disputes, weak successors, and external invasions, particularly by the Western Kshatrapas. Eventually, regional powers like the Ikshvakus and Pallavas emerged, replacing Satavahana dominance.

What was the legacy of the Satavahana Dynasty?

Their legacy includes the integration of North and South Indian cultures, the promotion of Buddhist art and architecture, and the establishment of trade and administrative systems that influenced future dynasties in the Deccan.

Did any notable female rulers belong to the Satavahana Dynasty?

Yes, Queen Nayanika (or Naganika) is a notable female figure who ruled as a regent for her son. Her role is documented in inscriptions like the Naneghat inscription, showcasing the involvement of women in governance.

What is the relevance of the Satavahanas in today’s context?

The Satavahana Dynasty exemplifies cultural pluralism, regional integration, and artistic excellence, values that remain relevant in modern Indian identity. Their history offers insights into how ancient India balanced diversity with unity, a lesson that resonates even today.