Introduction

Plato, a towering figure in the history of Western philosophy is renowned for his contributions to various philosophical fields, including metaphysics, ethics, politics, and epistemology. As the founder of the Academy in Athens, Plato established one of the earliest institutions of higher learning in the Western world. His dialogues, written in the form of conversations between his mentor Socrates and other prominent figures of his time, such as Aristotle and Parmenides, remain influential texts in philosophical discourse.

In this blog post, we aim to delve into the key ideas of Plato and their enduring relevance in contemporary society. Despite being composed over two millennia ago, his philosophical insights continue to resonate with modern thinkers, offering valuable perspectives on issues ranging from politics and ethics to the nature of reality and human knowledge.

Early Life and Education of Plato

Birth and Family Background

One of the most important thinkers in Western thinking, Plato was born in Athens, Greece, in 428 or 427 BCE. He was born under the name Aristocles and came from a wealthy and powerful political family. While his mother Perictione was linked to the renowned legislator Solon, his father Ariston traced his ancestry back to the mythical Athenian monarch Codrus.

His early life was steeped in the tumultuous politics of Athens, marked by the Peloponnesian War and the decline of Athenian democracy. Growing up in this environment would have undoubtedly influenced his later philosophical reflections on governance, justice, and the ideal state.

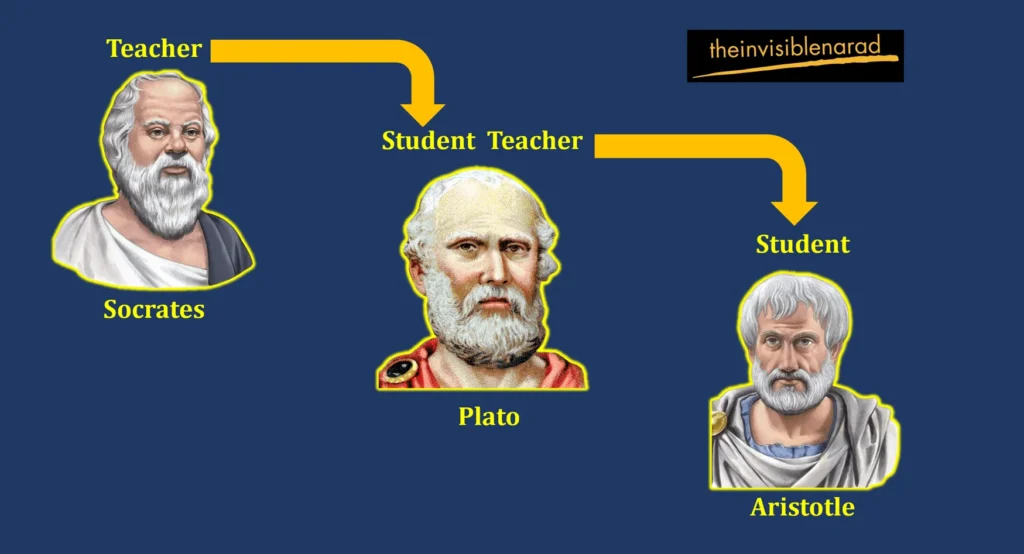

Education Under Socrates

His philosophical journey truly began when he became a disciple of Socrates, one of the most iconic figures in the history of philosophy. Socrates, known for his dialectical method and relentless questioning, left a profound impact on the young Plato. Under Socrates’ tutelage, Plato learned to question conventional wisdom, to seek truth through dialogue and reason, and to engage in critical thinking. The Socratic dialogues, written by Plato, immortalize the philosophical exchanges between teacher and student, showcasing Socrates’ profound influence on his intellectual development.

Influence of Pythagoreanism on Plato’s Philosophy

In addition to his education under Socrates, Plato was also influenced by the teachings of Pythagoras and his followers. Pythagoreanism was a philosophical and religious movement that emphasized the importance of mathematics, metaphysics, and the pursuit of wisdom. His exposure to Pythagorean ideas, possibly through his travels to Italy and Sicily, deeply impacted his own philosophical views.

One notable influence of Pythagoreanism on his philosophy was the concept of the soul’s immortality and its relationship to mathematical order. Pythagoreans believed in the transmigration of souls and saw mathematics as the key to understanding the harmony of the universe. He incorporated these ideas into his own philosophy, particularly in his dialogues such as the “Phaedo” and the “Republic,” where he explores the nature of the soul, its eternal existence, and its connection to the realm of Forms.

Furthermore, Pythagoreanism’s emphasis on abstract reasoning and the pursuit of truth through intellectual inquiry resonated with his own philosophical method. Like the Pythagoreans, he sought to uncover universal truths and to discern the underlying principles that govern reality.

Philosophical Ideas and Dialogues of Plato

Theory of Forms and Allegory of the Cave

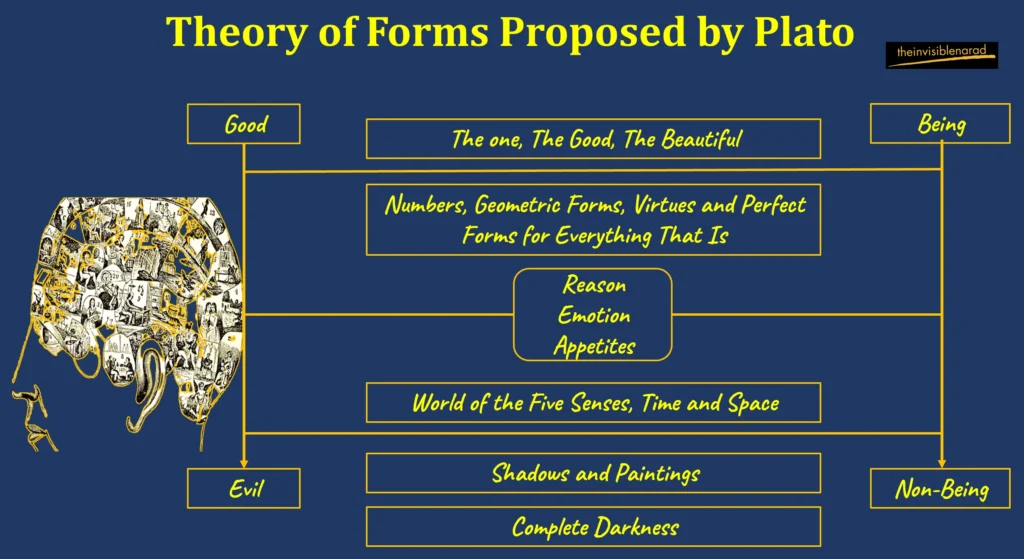

One of his central philosophical concepts is the Theory of Forms, also known as the Theory of Ideas. According to him, the material world perceived through our senses is merely a shadow or imperfect reflection of a higher realm of reality composed of eternal, unchanging Forms or Ideas. These Forms, which exist outside of the material world, are the actual essence or blueprint of things. As an illustration, consider the forms of goodness, justice, and beauty.

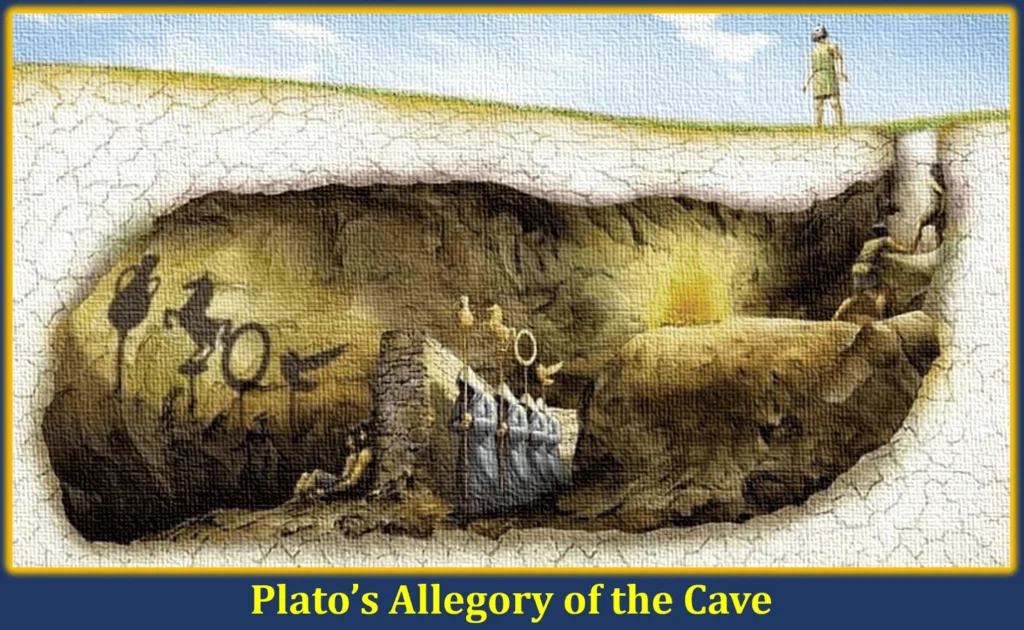

Plato illustrates the Theory of Forms vividly in his Allegory of the Cave, found in Book VII of “The Republic.” In this allegory, he describes a group of people who have been imprisoned in a cave since birth, chained in such a way that they can only see the shadows cast by objects passing in front of a fire behind them. The prisoners mistake these shadows for reality, unaware of the true nature of the objects causing them. He used this allegory to symbolize the journey of the philosopher, who escapes the confines of the cave and ascends into the sunlight of philosophical enlightenment, where he perceives the Forms directly.

Plato’s most famous dialogues and their themes

Republic

“The Republic” is perhaps his most famous work, presenting a comprehensive exploration of justice, governance, and the ideal state. Through the character of Socrates, Plato examines various definitions of justice and constructs an elaborate allegory of the soul, where he posits that the just individual mirrors the just state. The dialogue delves into the nature of the philosopher-king, the role of education in shaping moral character, and the concept of the tripartite soul.

The Symposium

“The Symposium” is a dialogue centered around a banquet attended by several prominent Athenians, including Socrates and the playwright Aristophanes. The dialogue explores the nature of love (eros) through a series of speeches delivered by different characters. Each speaker presents their understanding of love, ranging from the physical to the spiritual, culminating in Socrates’ speech, where he recounts the teachings of the priestess Diotima on the ladder of love, leading ultimately to the contemplation of Beauty itself.

Phaedrus

In “Phaedrus”, Socrates engages in a philosophical discussion with his friend Phaedrus on the nature of rhetoric and the soul. The dialogue unfolds as they discuss the art of persuasion and the importance of truth in speech. He uses the character of Socrates to critique the superficiality of rhetoric and advocate for the pursuit of genuine knowledge and wisdom.

Ethics and Virtue in Plato’s Philosophy

Ethics and virtue occupy a central place in his philosophy, intertwined with his exploration of the nature of reality and the human condition. He believed that living a virtuous life was essential for achieving eudaimonia, or human flourishing. He argued that true happiness comes from living in accordance with reason and moral excellence, rather than pursuing transient pleasures or material possessions.

In dialogues such as “The Republic” and “Phaedrus,” he presents various virtues, including wisdom, courage, moderation, and justice, as essential components of the virtuous life. He suggests that these virtues are interconnected and harmonized within the soul of the just individual.

Furthermore, his ethical theory is deeply influenced by his Theory of Forms, as he sees the Forms of the virtues as the ultimate standards by which human actions should be judged. By aligning oneself with the Forms of the virtues, individuals can achieve moral perfection and cultivate a harmonious relationship with the transcendent realm of reality.

Theory of Forms

Plato’s theory of Forms

Plato’s Theory of Forms, also known as the Theory of Ideas, is a central tenet of his philosophy. According to him, the material world perceived through our senses is transient, imperfect, and subject to change. In contrast, there exists a higher realm of reality, the world of Forms or Ideas, which is eternal, unchanging, and immutable. These Forms are the true essence or archetype of things, existing independently of the physical world.

He proposes that the Forms are the ultimate reality behind the appearances we perceive with our senses. For instance, there is a Form of Beauty, which serves as the standard by which we recognize and appreciate beauty in the physical world. Similarly, there are Forms of Justice, Goodness, and Virtue, which provide the foundation for moral understanding and ethical behavior.

Concept of Forms and their significance

The concept of Forms plays a crucial role in his philosophy, informing his views on metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics. The Forms serve as the basis for understanding the nature of reality and knowledge. He argues that true knowledge can only be attained through the contemplation of the Forms, rather than through sensory experience or empirical observation alone. The intellect, guided by reason, is capable of grasping the eternal and unchanging Forms, leading to genuine understanding and wisdom.

Moreover, the Forms have profound implications for ethics and moral philosophy. He suggests that the Forms of the virtues, such as Justice and Goodness, provide objective standards by which human actions should be judged. Living a virtuous life entails aligning oneself with the Forms, thereby achieving harmony with the transcendent realm of reality and attaining eudaimonia, or human flourishing.

Furthermore, the Forms serve as a metaphysical framework for his theory of knowledge. He distinguishes between opinion (doxa), based on the mutable world of appearances, and true knowledge (episteme), derived from contemplation of the unchanging Forms. By ascending from the sensible realm to the intelligible realm through dialectical inquiry and philosophical reflection, individuals can attain genuine knowledge of the Forms.

Criticisms and modern interpretations of the Theory of Forms

Despite its enduring influence, his Theory of Forms has faced numerous criticisms and challenges over the centuries. One criticism is the problem of participation, which questions how individual objects in the physical world can participate in or resemble the transcendent Forms. Critics argue that this notion raises metaphysical and epistemological difficulties, such as the nature of the relationship between the Forms and the particulars they instantiate.

Another criticism is the issue of universals and particulars, which raises questions about the ontological status of the Forms and their relation to individual objects. Some philosophers contend that Plato’s theory leads to a problematic dualism between the realm of Forms and the world of particulars, complicating the process of explaining how they interact.

Modern interpretations of the Theory of Forms vary widely, with some philosophers seeking to reinterpret his ideas in light of contemporary metaphysics and epistemology. Some scholars emphasize the symbolic or metaphorical significance of the Forms, suggesting that they represent abstract principles or conceptual categories rather than transcendent entities. Others explore the parallels between his Forms and modern theories in fields such as mathematics, linguistics, and cognitive science, highlighting the enduring relevance of his insights to contemporary philosophical inquiry.

Allegory of the Cave: Shedding Light on Perception and Reality

Allegory of the Cave from Plato’s “Republic”

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave is a thought-provoking allegory found in Book VII of his seminal work, “The Republic.” In this allegory, Plato employs a vivid metaphor to illustrate the journey from ignorance to enlightenment, emphasizing the distinction between perception and reality.

The allegory depicts a group of individuals who have been imprisoned since birth inside a dark cave, with their legs and necks bound in such a way that they can only see the wall in front of them. Behind them, there is a fire casting shadows on the wall, and between the fire and the prisoners, there is a raised platform along which puppeteers move various objects, casting shadows on the wall. The prisoners mistake these shadows for reality, unaware of the true nature of the objects causing them.

One of the prisoners eventually escapes from the cave and emerges into the sunlight, experiencing the world outside for the first time. Initially blinded by the brightness, the freed prisoner gradually adjusts to the light and begins to perceive the true forms of objects, realizing that the shadows he once mistook for reality were mere illusions.

Upon this realization, the freed prisoner feels compelled to return to the cave and enlighten his fellow prisoners about the existence of the outside world and the true nature of reality. However, when he tries to convey his newfound knowledge, the other prisoners reject his words, clinging stubbornly to their familiar beliefs and perceptions.

Allegory’s meaning and its relevance in contemporary society

The Allegory of the Cave serves as a powerful metaphor for the human condition and the journey from ignorance to enlightenment. It highlights the limitations of sensory perception and the importance of critical thinking and philosophical inquiry in uncovering deeper truths about reality.

In contemporary society, the allegory remains relevant in various contexts, particularly in the age of information overload and digital media. Like the prisoners in the cave, many individuals may be trapped in a world of illusion, shaped by societal norms, cultural beliefs, and media representations. The allegory challenges us to question the validity of our perceptions and to seek knowledge beyond superficial appearances.

Furthermore, the allegory warns against the dangers of intellectual complacency and ideological conformity. In an era marked by echo chambers and confirmation bias, the allegory encourages us to break free from the confines of our own perspectives and to engage in open-minded dialogue with others, even if it challenges our preconceived notions.

Application of the allegory to various aspects of life

The Allegory of the Cave can be applied to various aspects of life, including education, politics, and personal development:

- Education: The allegory underscores the importance of a well-rounded education that encourages critical thinking, intellectual curiosity, and independent inquiry. It calls into question traditional methods of rote memorization and passive learning, advocating instead for an education that fosters intellectual liberation and self-discovery.

- Politics: The allegory offers insights into the nature of power and manipulation in politics. Like the puppeteers in the cave, political elites may control the narrative and manipulate public opinion through propaganda and misinformation. The allegory urges citizens to question authority and to scrutinize the sources of information they encounter.

- Personal development: On a personal level, the allegory encourages self-reflection and introspection. It prompts individuals to examine the beliefs and assumptions that shape their worldview and to consider the possibility of transcending personal biases and limitations. By embracing a spirit of intellectual humility and openness to new ideas, individuals can embark on their own journey of enlightenment and self-discovery.

His Allegory of the Cave continues to captivate and inspire audiences with its timeless exploration of perception, reality, and the quest for truth. As a metaphor for the human condition, it challenges us to break free from the shadows of ignorance and to embrace the light of knowledge and understanding.

Plato’s Political Philosophy

Plato’s vision for the ideal state in “The Republic”

In “The Republic,” Plato presents his vision for the ideal state, outlining a blueprint for a just and harmonious society governed by philosopher-kings. His ideal state is structured according to a hierarchical model, with three distinct classes: the ruling class of philosopher-kings, the auxiliary class of guardians, and the productive class of workers.

At the apex of Plato’s ideal state are the philosopher-kings, individuals who have undergone rigorous intellectual and moral training, culminating in the attainment of wisdom and virtue. He argued that philosophers, by virtue of their love of wisdom and commitment to the pursuit of truth, are best suited to govern the state. Unlike traditional rulers motivated by self-interest or ambition, philosopher-kings are guided by reason and a genuine concern for the well-being of the citizens.

The auxiliary class of guardians serves as the protectors and enforcers of the state, embodying qualities of courage, discipline, and loyalty. Trained from a young age in physical and military education, the guardians are responsible for maintaining order, defending the state from external threats, and upholding the laws and principles of justice.

Finally, the productive class of workers fulfills the economic needs of the state, engaging in agriculture, craftsmanship, and trade. While lacking the intellectual and moral virtues of the ruling and auxiliary classes, the workers contribute to the material prosperity of the state through their labor.

Plato’s ideal state is characterized by a strict division of labor, communal property, and a system of education designed to cultivate virtue and harmony among its citizens. The ultimate goal of the ideal state is to achieve justice, defined as the harmonious integration of the individual soul with the social order, where each individual fulfills their designated role for the greater good of the community.

Role of philosopher-kings and the guardians

In Plato’s political philosophy, the philosopher-kings and guardians play crucial roles in the governance and protection of the ideal state. The philosopher-kings, as the rulers of the state, possess the wisdom, moral integrity, and intellectual acumen necessary to make decisions for the common good. Their primary responsibility is to govern with justice and virtue, ensuring the well-being and flourishing of all citizens.

The guardians, on the other hand, serve as the defenders and enforcers of the state, upholding the laws and principles established by the philosopher-kings. Trained in physical and martial skills, the guardians are entrusted with the task of maintaining order, protecting the state from internal discord and external threats, and preserving the integrity of the social order.

Both the philosopher-kings and guardians are expected to embody the highest ideals of wisdom, courage, and selflessness. They are duty-bound to prioritize the interests of the state over their own personal desires or ambitions, acting as benevolent rulers and protectors who govern with wisdom and compassion.

Relevance of Plato’s political philosophy in Contemporary Times

Plato’s political philosophy continues to provoke debate and inspire reflection on the nature of governance, justice, and the ideal society. While some aspects of Plato’s vision may seem utopian or impractical in contemporary times, his ideas remain relevant in several ways:

- Leadership and governance: Plato’s emphasis on the importance of wise and virtuous leadership resonates with contemporary discussions about the qualities and responsibilities of political leaders. In an era marked by political polarization and ethical challenges, Plato’s vision of philosopher-kings reminds us of the value of leadership grounded in reason, integrity, and a commitment to the common good.

- Education and civic virtue: Plato’s advocacy for a system of education designed to cultivate moral and intellectual virtues among citizens remains pertinent in contemporary debates about the purpose of education and its role in fostering civic engagement and social cohesion. Plato’s emphasis on the transformative power of education underscores the importance of instilling values of justice, critical thinking, and ethical responsibility in future generations.

- Justice and social order: Plato’s conception of justice as the harmonious integration of the individual soul with the social order invites reflection on contemporary issues of social justice, inequality, and the distribution of resources. While Plato’s ideal state may be impractical or unattainable in its entirety, his exploration of the principles of justice and the ideal society encourages us to strive for greater equity and fairness in our own political and social systems.

His political philosophy offers a rich tapestry of ideas and insights into the nature of governance and the quest for the ideal society. While his vision may be subject to criticism and reinterpretation, the enduring relevance of Plato’s ideas reminds us of the enduring quest for justice, wisdom, and virtue in the realm of politics and human affairs.

Legacy and Influence of Plato’s Works

Impact on Western Philosophy and Education

Plato’s works have had a profound and enduring impact on Western philosophy and education, shaping the intellectual landscape for centuries. His dialogues, such as “The Republic,” “The Symposium,” and “Phaedo,” continue to be studied and debated in philosophy classrooms around the world.

Plato’s contributions to philosophy are multifaceted. His Theory of Forms, Theory of Knowledge, and political philosophy have left an indelible mark on the history of Western thought. The concept of the Forms, with its emphasis on transcendent truth and eternal principles, has influenced subsequent philosophical movements, including Neoplatonism, idealism, and existentialism.

Moreover, Plato’s educational philosophy has had a lasting impact on pedagogy and curriculum development. His emphasis on the importance of dialectical inquiry, critical thinking, and moral education has informed educational practices from antiquity to the present day. The Socratic method, characterized by probing questions and collaborative dialogue, remains a cornerstone of effective teaching and learning.

Interpretations and Criticisms of Plato’s Ideas

While Plato’s ideas have been widely celebrated, they have also been subject to interpretation and criticism. Scholars and philosophers have offered diverse interpretations of Plato’s works, leading to debates over the meaning and significance of his philosophical concepts.

One area of contention is Plato’s Theory of Forms, which has been criticized for its metaphysical complexity and reliance on abstract entities. Critics argue that the Forms raise difficult questions about the relationship between universals and particulars, as well as the nature of causation and ontology.

Additionally, Plato’s political philosophy has faced criticism for its authoritarian implications and idealized vision of governance. Critics question the feasibility of Plato’s ideal state, arguing that it is impractical and potentially oppressive. Moreover, Plato’s exclusion of certain groups, such as women and manual laborers, from the ruling class has been criticized as elitist and discriminatory.

Relevance of Plato’s Philosophy in Modern Society

Despite these criticisms, Plato’s philosophy remains relevant in modern society, offering insights into timeless questions about reality, knowledge, ethics, and governance. His exploration of the nature of justice, the pursuit of wisdom, and the ideal society continues to resonate with contemporary concerns and challenges.

In an age marked by technological advancements, globalization, and social upheaval, Plato’s emphasis on the importance of moral education, critical thinking, and civic engagement holds particular relevance. His call for individuals to question authority, examine their own beliefs, and strive for a deeper understanding of truth speaks to the need for intellectual curiosity and moral responsibility in navigating complex ethical dilemmas and societal issues.

Moreover, Plato’s critique of democracy and his advocacy for philosopher-kings invite reflection on the nature of political leadership and the qualities of effective governance. While Plato’s ideal state may be impractical in its entirety, his exploration of the principles of justice, virtue, and the common good encourages us to aspire to higher standards of ethical conduct and social justice in our own political systems.

His legacy continues to endure as a source of inspiration and intellectual inquiry in the contemporary world. His works challenge us to grapple with fundamental questions about the nature of reality, knowledge, and human flourishing, offering a timeless guide for navigating the complexities of the human experience.

Dialogue Writing and Teaching Method of Plato

Socratic Method in Plato’s Dialogues

Plato’s dialogues are renowned for their use of the Socratic method, a dialectical approach to philosophical inquiry named after Plato’s teacher, Socrates. The Socratic method is characterized by a rigorous process of questioning and critical examination, aimed at eliciting deeper insights and uncovering underlying assumptions.

In Plato’s dialogues, Socrates engages in philosophical discussions with various interlocutors, probing their beliefs, challenging their arguments, and exposing inconsistencies in their reasoning. Through a series of probing questions and logical deductions, Socrates guides his interlocutors toward a greater understanding of truth and wisdom.

The Socratic method is marked by its emphasis on dialogue, collaboration, and intellectual exchange. Rather than presenting philosophical doctrines or dogmas, Plato uses the dialogic format to encourage readers to actively engage with the ideas presented, fostering a spirit of inquiry and critical thinking.

Role of Dialogues in Conveying Philosophical Concepts

Plato’s dialogues serve as vehicles for conveying a wide range of philosophical concepts, from metaphysics and epistemology to ethics and political theory. Through the dynamic interplay of characters and ideas, Plato explores complex philosophical themes in a accessible and engaging manner.

One of the key functions of the dialogues is to challenge readers to question their assumptions and reconsider their beliefs. By presenting conflicting viewpoints and engaging in dialectical exchanges, Plato encourages readers to think critically about the nature of reality, knowledge, and morality.

Moreover, the dialogues are instrumental in illustrating philosophical concepts through concrete examples and vivid imagery. Plato often uses allegories, analogies, and parables to elucidate abstract ideas, making them more accessible and comprehensible to readers

Furthermore, the dialogic format allows Plato to explore the implications of philosophical theories in practical contexts. Through the interactions of characters and the unfolding of narrative, Plato demonstrates how philosophical ideas play out in the real world, highlighting their relevance to human experience and societal concerns.

Influence of Plato’s Teaching Style on Future Philosophers

Plato’s teaching style and use of the Socratic method have had a profound influence on future philosophers and educators. His dialogues set a precedent for philosophical inquiry as a collaborative and interactive process, challenging students to engage actively with philosophical ideas rather than passively receiving information.

The Socratic method, with its emphasis on critical questioning and open dialogue, has become a hallmark of philosophical pedagogy. It continues to be employed in classrooms and academic settings as a means of stimulating intellectual curiosity, fostering analytical skills, and promoting deeper understanding.

Moreover, Plato’s dialogues have inspired countless philosophers and thinkers throughout history, from Aristotle to Immanuel Kant to Friedrich Nietzsche. His innovative approach to philosophical writing, combining narrative flair with rigorous argumentation, has shaped the style and structure of philosophical discourse for centuries.

His dialogue writing and teaching method represent a pioneering approach to philosophical inquiry that remains influential and relevant in the contemporary world. Through the Socratic method, Plato invites readers to embark on a journey of intellectual discovery, challenging them to question assumptions, explore new ideas, and pursue the truth wherever it may lead.

Plato’s Views on Art, Beauty, and Soul

Theory of Art and Critique of Mimesis

Plato’s views on art, particularly his theory of art and his critique of mimesis, are expounded upon in various dialogues, notably in “The Republic” and “Ion.” Plato’s theory of art is deeply influenced by his broader philosophical convictions, particularly his belief in the existence of transcendent Forms or Ideas.

In “The Republic,” Plato famously criticizes mimesis, the imitation or representation of the physical world in art, as a mere copy of a copy. He argues that artists produce imitations of objects that are themselves imitations of the Forms, resulting in an inferior and deceptive form of knowledge. According to him, the arts, including poetry, drama, and painting, are far removed from the realm of truth and contribute little to the cultivation of virtue and wisdom.

Plato’s critique of mimesis is motivated by his concern for the moral and intellectual effects of art on society. He worries that the arts can evoke irrational emotions, cloud judgment, and lead individuals away from the pursuit of truth and goodness. As such, Plato advocates for strict censorship of the arts in his ideal state, reserving only those forms of art that promote moral and intellectual upliftment.

Concept of Beauty and its Relationship to the Good

Plato’s philosophy of beauty is intimately connected to his broader metaphysical and ethical framework. In “Symposium” and “Phaedrus,” Plato explores the nature of beauty and its relationship to the Good, the ultimate Form that embodies perfection and harmony.

Plato conceives of beauty as a reflection or manifestation of the Form of the Good. He argues that beauty, whether in physical objects, artworks, or moral qualities, is a visible and tangible expression of the underlying unity and order of the universe. True beauty, according to him, transcends the merely sensory and evokes a sense of awe and reverence, leading the soul towards contemplation of the divine.

Furthermore, Plato suggests that beauty has the power to elevate the soul and inspire moral transformation. By contemplating beauty in its various forms, individuals can attain a deeper understanding of the Good and strive to align themselves with its principles. Thus, beauty serves as a guiding beacon on the path towards virtue and enlightenment.

Immortality of the Soul in Plato’s Philosophy

Plato’s conception of the soul as immortal and divine is a central tenet of his philosophy, explored in dialogues such as “Phaedo” and “Phaedrus.” Plato argues that the soul, being incorporeal and immutable, is not subject to the same laws of decay and mortality as the body.

According to him, the soul is a divine essence, belonging to the realm of the Forms and participating in the eternal and unchanging realities. While the body is transient and perishable, the soul is immortal and eternal, capable of transcending the limitations of the physical world.

Plato offers various arguments for the immortality of the soul, including the theory of recollection, the affinity argument, and the harmony argument. He suggests that the soul, having existed prior to birth, possesses innate knowledge of the Forms, which it recollects through philosophical inquiry. Moreover, the soul’s affinity with the divine and its inherent harmony with the principles of the Good ensure its continued existence beyond the confines of the body.

Plato’s belief in the immortality of the soul has profound implications for his ethical and metaphysical teachings. It underscores the importance of cultivating the soul through philosophical contemplation and moral excellence, as well as the conviction that death is not to be feared but embraced as a transition to a higher state of existence.

His views on art, beauty, and the soul represent a rich and multifaceted exploration of fundamental questions about the nature of reality, knowledge, and human flourishing. His critique of mimesis, his conception of beauty as an expression of the Good, and his belief in the immortality of the soul continue to inspire philosophical inquiry and reflection in the contemporary world.

Conclusion & FAQs

Throughout this blog post, we have explored various aspects of Plato’s philosophy, including his dialogue writing and teaching method, his views on art, beauty, and the soul. We discussed Plato’s use of the Socratic method in his dialogues, the role of dialogues in conveying philosophical concepts, and the influence of Plato’s teaching style on future philosophers. Additionally, we examined Plato’s views on art, beauty, and the soul, including his critique of mimesis, his conception of beauty as related to the Good, and his belief in the immortality of the soul.

Plato’s philosophy remains profoundly relevant in the contemporary world, offering insights into timeless questions about reality, knowledge, ethics, and governance. His emphasis on critical thinking, moral education, and the pursuit of truth continues to inspire philosophical inquiry and reflection. Moreover, Plato’s ideas have influenced a wide range of modern concepts and movements, including idealism, existentialism, and educational theory.

This blog post only scratches the surface of Plato’s vast body of work and the depth of his philosophical insights. There is much more to explore and discuss, from his metaphysical theories to his ethical teachings to his literary style. I invite readers to delve deeper into Plato’s dialogues, to engage with his ideas critically, and to participate in ongoing conversations about his legacy and influence.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How did Plato’s upbringing influence his philosophical ideas?

Plato’s upbringing in Athens, Greece, and his education under the tutelage of Socrates played a significant role in shaping his philosophical ideas. His exposure to the vibrant intellectual and cultural milieu of Athens, as well as his close association with Socrates, profoundly influenced his philosophical outlook and method of inquiry.

What is the significance of Plato’s theory of Forms in his philosophy?

Plato’s theory of Forms, also known as the Theory of Ideas, is a central tenet of his philosophy. It posits the existence of eternal, unchanging Forms or Ideas as the ultimate reality behind the material world. The theory of Forms informs Plato’s views on metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and aesthetics, providing a framework for understanding the nature of reality and knowledge.

How has Plato’s philosophy been interpreted and criticized over the centuries?

Plato’s philosophy has been interpreted and criticized in diverse ways over the centuries, reflecting changing intellectual and cultural contexts. While many philosophers have been inspired by Plato’s ideas and sought to develop or expand upon them, others have offered critiques and alternative interpretations. Plato’s views on topics such as politics, art, and the soul have been subject to intense debate and scrutiny, leading to a rich and multifaceted body of scholarship.

What modern concepts or movements have been influenced by Plato’s works?

Plato’s works have influenced a wide range of modern concepts and movements, including idealism, existentialism, and educational theory. His emphasis on the pursuit of truth, the cultivation of virtue, and the importance of moral education continues to resonate with contemporary concerns and challenges. Moreover, Plato’s dialogues, with their use of the Socratic method and exploration of philosophical themes, have served as a model for philosophical inquiry and dialogue in the modern era.

How did Plato’s dialogues contribute to the development of philosophical discourse?

Plato’s dialogues represent a seminal contribution to the development of philosophical discourse. Through the use of the Socratic method and dialogic style, Plato engaged readers in critical inquiry and philosophical exploration. His dialogues presented diverse viewpoints and explored complex philosophical themes, stimulating intellectual curiosity and fostering a deeper understanding of the human condition. Plato’s dialogues continue to serve as a model for philosophical inquiry and dialogue in the contemporary world, inspiring ongoing exploration and discussion of philosophical ideas.

The breadth of knowledge compiled on this website is astounding. Every article is a well-crafted masterpiece brimming with insights. I’m grateful to have discovered such a rich educational resource. You’ve gained a lifelong fan!